The Berlin Philharmonic's Direct-To-Disc Brahms Symphonic Cycle Conducted By Sir Simon Rattle

Proposing to a distinguished orchestra like the Berlin Philharmonic and its conductor, a logistically, artistically and technically complex and risky project like this one would be improbable in any year, but forty years into the digital recording era, it’s miraculous, though their agreeing to it is even more so.

The last time the orchestra recorded direct to disc was seventy years ago, before the advent of magnetic recording tape. These were the first D2D recordings ever made in this home of the Berlin Philharmonic, the construction of which began in 1960 and was completed three years later. It is a pioneering, much copied proscenium-free design with “vineyard-style” seating.

The almost half-ton Neumann VMS-80 lathe had to be carefully transported from the Emil Berliner Studios to the concert hall, which fortunately was but a third of a mile away. Once there it had to be re-calibrated and readied for the schedule, which consisted of the four Brahms symphonies performed twice within a two-week period.

The general rehearsal was also cut to disc, giving the producers three shots to get perfectly recorded sides, both technically and of course musically. Following rehearsal experiments, recording producer Rainer Maillard chose to hang one meter behind and four and a half meters above the conductor’s head, a single crossed pair of Sennheiser MKH800 Twin condenser microphones in a classic Blumlein array.

Of course neither the notes played nor the instrumental balance could be adjusted once they had been committed to lacquer. What’s more, unlike when cutting from tape, mastering engineer Maarten DeBoer could not make use of a preview head to “tell” the lathe how to adjust the groove pitch for louder, more dynamic passages, so he was left to do it manually by anticipating what was coming. Set the pitch too wide, too often and you run out of real estate. Set it too narrow and you risk groove overlap.

Now add the pressure of having to replace the lacquer and start cutting “live” between movements and you begin to appreciate the high stakes for everyone involved. A red light on the podium visible only to the Maestro was his signal to cue the orchestra. After a series of rehearsals, the time between lacquer changes was reduced to but a few seconds, which, according to the annotation felt like “…an eternity to the participants…”.

In between lacquers, according to the annotation, “Sir Simon bridged the time dabbing his foreheard”. The audience was never alerted to any of this “….in order to prevent psychological pressure from inadvertently increasing the tickle in the throat of cough-prone listeners.”

Speaking of which, my first play through the six sides I didn’t notice a cough or a creaking seat until the first movement of Symphony Nr. 4, which was the second side of the fifth LP. In fact, I listened before reading any of the notes and wasn’t aware these were “live” in front of an audience recordings until the applause at the end of the first symphony.

The second listen through I heard a few more coughs but they are so down in level that they are easy to miss. The lack of extraneous audience noise was yet another remarkable aspect of this production.

Another was that unlike many “live in concert” recordings that I’ve heard, this one does not sound like a radio broadcast, probably in part because of the microphone placement and pattern and in part because of audience discipline even if they were unaware of the recording.

What else could it be? I had for many years a twentieth row center subscription seat to The New York Philharmonic and sometimes around me it sounded like a hospital ward. Audience noise will not distract from your enjoyment of these recorded performances.

A great deal more fascinating and pressure producing backstory exists around the orchestra’s history with the composer, but I’m going to leave that for what I hope in Stereophile will be a somewhat different look at this box.

The Presentation

The packaging is equal to the lavishly produced RCA Victor Soria series sets (named after the producer Dorle Soria) from the ‘late ‘50s and early ‘60s. The six LPs and hard covered book are housed in a notably sturdy canvas-clad (or canvas-like) box. The records are each in a plastic-lined sleeve that’s in a “library green” outer sleeve, the color of which well-complements the box’s pale green color. The hard covered seventy two-page book follows the canvas motif and is of equal high quality in terms of the paper stock, layout, printing and especially the content in both German and English.

High quality photos are affixed to the page paper as in the old Soria series, which allows the use of really attractive paper stock. The look and feel of the book is “old school” excellence.

The book begins with a page for each of the four symphonies. Each piece gets a long, single paragraph descriptive “play by play” to the right of which is a listing giving the year of its composition, the first performance, date and who conducted what orchestra, as well as the Berlin Philharmonic’s first performance and who conducted, followed by the instrumentation.

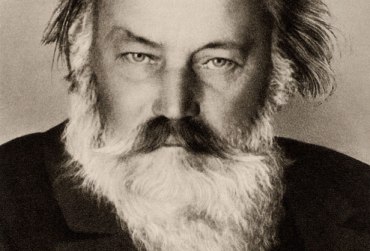

Next up is a provocative, remarkably detailed essay (especially given that all of this occurred before there were recording devices) called “Constellations”, which provides a far reaching look at the composer’s life, times, work and contemporaries (Wagner and Bruckner among others, and of course always in the shadows, Beethoven).

Written by Wolfgang Sandberger, Director of the Brahms institute at the Jusikhochschule Lubeck, the essay had me simultaneously thinking of academia and “Entertainment Tonight”—and I mean that in a good way.

That’s followed by Wolfgang Stähr’s essay, which provides a fascinating history of the close relationship between Brahms and the Berlin Philharmonic, as well as how the orchestra’s conductors over the years have fared interpreting and bringing to musical life the four symphonies. As the author puts it “For the Berliner Philharmoniker, its self-perception, its aesthetic, its stylistic and, in the broadest sense, its culturally defined identity, the four symphonies (and four concertos), of Johannes Brahms have always been indespensible, right from the beginning, a seal of approval and certificate of authenticity: are the Philharmonic still the Philharmonic? For the orchestra’s principal conductors, however, the interpretation of Brahms also became the equivalent of an initiation ritual, a final exam and a patent of nobility.”

And you thought Maestro Rattle at the podium was dabbing his forehead worrying about the cutting stylus creating the lead in groove before he lowers the baton?

Finally, before the credits and the names of all of the orchestra members, there’s an essay by co-producer Rainer Maillard providing the direct to disc rationale and explaining the process and the problems that occurred during the production, including one side for which none of the three recordings was found to be useable and so, for that side, an analog backup tape was used. Which side was it? I’ll have to go back and listen for it!

No, it’s not Rick Rubin!

The Four Brahms Symphonies

I write about classical music with a great deal of trepidation—though not as much as Brahms obviously had about writing symphonies.! He didn’t attempt his first until he was well into his career and fame. Once he starting writing, he took his time finishing it—fifteen years.

However, I go back a long way with Brahms. In 1979 when I worked on “Animalympics” I chose the for the Flamingo skater Dorie Turnell’s performance (at 18:48), a section of the third movement of Brahm’s Fourth Symphony.

I chose it because I knew it well along with the other three, thanks to my “go to” box set Bruno Walter Conducts The Orchestral Music of Brahms (Columbia M4S 615) with the west coast version of the Columbia Symphony released in 1960. The Concertmaster, Israel Baker played with Heifetz, Menuhin, Glen Gould and Tom Waits, while Harold Dicterow the principal second violinist, was long a member of the L.A. Philharmonic and his son Glenn was, for many years, concertmaster when I had my subscription to The New York Philharmonic.

However, my favorite among the four is the fourth. It is Brahms’ symphonic pinnacle in terms of its composition but more so from the perspective of a casual classical listener (I plead guilty), it’s the most dramatic, immediately memorable and easiest to follow. If you want to hear it taken apart, Leonard Bernstein does a great job of it in this YouTube audio transcription of a Book-of-the Month Club record in which he also outlines how poorly the fourth symphony was received by many and why. If you want to understand how a symphony is constructed using the fourth as a roadmap, please listen!

Interestingly, in 2008 Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic recorded before a live audience another Brahms symphony cycle. It would be interesting to compare the two musically and sonically but I didn’t in preparing for this review.

There are dozens of Brahms symphonic cycles on record and CD and there are those who have gone through them and have opinions about which is best. That wouldn’t be me. But this is not about finding the best interpretation. This is about what is without a doubt a very fine performance recorded direct-to-disc, which sets it apart from all of the others.

The Sound

In choosing to record a symphony orchestra with but a single stereo pair of microphones, the producer is attempting to correctly present the orchestra spatially in three-dimensions. In other words, you should be able to sit down, put on one of these sides, and assuming your system is reasonably time and phase coherent, experience the sensation of orchestral near “virtual reality” with but two stereo speakers.

The surround sound people will tell you they own that space, but as long as you’re willing to ignore (though not completely) the missing rear hall reverberant cues and the audience appearing behind the orchestra as opposed to your being seated in the audience, you’ll experience through these six records a thrilling illusion of having an orchestra playing before you.

As in the picture, the orchestra is laid out sonically in an intimate “U” shape with the first and second violins opposite his left and right ears. To get the most here don’t be afraid to crank it up a bit. At full tilt a symphony orchestra can easily produce 100dB or more.

If you listen at too low a level the sound can be somewhat washed out and even at sufficiently high SPLs if I have any criticism of the recording it’s that instrumental harmonics can be somewhat less than fully fleshed out, though the balance of what’s there is superb and helps create a coherent tonal picture.

The ear and the microphone don’t hear things identically, which is where spot mics come in, but they mess with timing and phase and produce incoherent and artificially “inflated” pictures.

In some ways I’m reminded of Keith O. Johnson recordings: the spread is fifth row wide, but the perspective is more mid-hall.

The sonic thrill here then is the fleshed out image three dimensionality and the transient delicacy.

You “see” the strings and “feel” the textures in a very physical way. Brahms’ Third Symphony is his most disturbing and conflicted and when he uses the strings to sound the alarm, you’ll feel it.

However, if you’re expecting the vivid, super-transparent, “widescreen” K.E. Wilkinson Kingsway Hall type recordings, you won’t get them here. Those are sonically thrilling but hardly what you really hear live, especially in a hall that lacks a proscenium type stage.

Instead of stage-rear reflections, there’s an open, dark space behind the orchestra, which intensifies the image and staging three-dimensionality, as does what sounds like a hall with generally fast reverb times with a fast clean decay. If that’s wrong, please let me know. I’ve never been there.

However, I’ve certainly seen many concerts at now Geffen Hall and elsewhere and this recorded sound is in some ways more like what you hear “live” than are many hall recordings produced to create a less natural, but more intimate and “entertaining” effect. If that’s what you’re used to, you may have to acclimate your ears to this sound. Of course no microphone or recording can produce an identical experience to “live”, but getting the spatial cues on target really helps! If you were to ask me for the recording’s main shortcoming it would be less than full transparency, but then I’m not familiar with the chosen Sennheiser microphone.

I’d like to hear an engineer or two chime in especially after hearing this set, the announcement of which got some online critics exercised. My favorite:

“Such a bizarre and dogmatic concept... purism for purism's sake... entirely driven by marketing...

It's like setting up a huge view camera and making a contact print, and pretending that this is the "true" representation of the subject.

Unfortunately, music is only capable of generating or changing a mood or emotion, so bringing that about often requires editing, and tweaking the sound, etc...

On the other hand, here we are, talking about it.. so they've already won..!!”

In other words, attending a live performance can’t generate moods and emotions because it’s not edited? And live performances are also “bizarre and dogmatic concepts”.

Here’s another “fan”:

“Yes, I saw that a week or two ago and was repulsed not so much by the price (which is extortionate) as the implication that recording in this fashion will give superior results to using the best digital techniques available for capturing the performances.

When Berlin Philharmonic started its own in-house label, I thought this was a lovely opportunity to bring reference quality recordings to the dwindling classical music audience at decent prices by cutting out the middle man rather than a profit driven highly exclusive, expensive packaging based commercial venture.

Shame on them...”

Yikes!

Vinyl

Things got off to a rough start as there were a few instances of the kind of tearing sound associated with “non-fill”. Fortunately there were only two short ones. Otherwise the pressings were flat quiet, and concentric. I don’t know where these were pressed but I’m assuming Optimal.

Conclusion

To be able to get a Brahms symphonic cycle performed by one of the world’s great orchestras and distinguished conductors, recorded AAA D2D minimally miked is no small miracle. That it was recorded live in performance makes it more vital. The performances are not cautious or tepid because lacquers were being cut and the intrusion of extraneous audience produced noises is mimimal to mostly non-existent..

I wonder how the members of the orchestra feel about this set. Or whether the Maestro is happy with the performances and their being committed to vinyl live, without edits. And I wonder what is the producers’ and cutting engineer’s honest assessment of the sonic results. You can be sure that along with the analog tape “safety” copy, the performances were digitally recorded (perhaps I’m wrong). If so, I’d sure like to hear those too.

I hope to find out if I can arrange interviews with any of the principals. If so, they will appear in Analog Corner in Stereophile.

This is an expensive, but seriously well-done box set and while people can argue about what is the best Brahms cycle (some say its Claudio Abaddo’s with the Berlin Philharmonic), this is the only one done D2D and if eliminating the digits matters at all to you, here you go! And I hear you: “If you can’t tell which side is from tape, what’s the point of D2D”? Well I wasn’t listening for the tape, I was too busy enjoying the music, and that’s the main point. Isn’t it? The set is limited to 1833 copies, which is the year of Brahms's birth.