Bruce Springsteen: The Album Collection Vol. 1 1973-1984 Reviewed

Among the comments you’ll find if you go there is this one from “AbsolutelyRight” who writes: “I hope the shipment overheats and all the vinyl gets warped for this no-good overrated leftist putz and his psychotic sycophant neanderthal fans.”

That well inoculates me for any less than salutary opinions I might offer here don’t you think? Rather than reviewing the albums individually as we did with The Beatles in Mono box set, we’ll cover this set in a single sitting.

Bob Ludwig re-mastered all of these albums using the original analog master tapes, with two exceptions: The River, which was originally mixed directly to 44.1k/16 bit PCM on U-Matic video cassette tape via a Sony 1610 digital recorder and Nebraska, which was originally recorded on a four track Tascam PortaStudio cassette recorder that Ludwig had transferred to 1/2” analog reel-to-reel tape before mastering the album for its original vinyl release back in 1982. Ludwig’s been mastering Springsteen projects ever since.

Born to Run got the gold CD treatment mastered by Ludwig as part of Sony’s wildly uneven 1992 Mastersound Gold CD reissue series and was later re-mastered by him yet again at 16 bit resolution for a box set (and again in 2005 for the 30th anniversary reissue) as was Darkness on the Edge of Town. The other five have never been re-mastered after their CD debuts. Ludwig says that Springsteen told him backstage that the 30th anniversary mastering was the first time he'd heard it as he'd originally envisioned it.

The impetus for these 24 bit reissues was Apple’s “Mastered for iTunes” initiative, though for now once Apple gets the files it still encodes to 44.1 KHz, 256 Kbps AAC (which are bigger files than standard 44.1k/16 bit rips).

Everyone on the Springsteen team was onboard to improve the early catalogue’s sound quality, including Bruce himself, as well as Jon Landau (who as a music critic for Boston’s Real Paper wrote “I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen” and then became his manager) and of course Springsteen’s engineer/archivist Toby Scott.

For this go round Springsteen himself chose to go with Jamie Howarth’s “Plangent Process” after hearing a demonstration upon Ludwig's suggestion. I first met Howarth at an AES a few years ago. He described his innovation and expressed to me his frustration at not being able to get many record labels onboard I think at that point “any labels” would be more accurate) to use the process that corrects in the digital domain many measurable tape playback timing issues like scrape flutter caused by the friction of the tape rolling across the playback head.

Howarth had gotten the Grateful Dead interested and he did the tape transfer using the Plangent Process for the 3 CD Rhino-issued set The Grateful Dead Live at the Cow Palace: New Year’s Eve 1976. Howarth sent me a set of CD-Rs and the sound was smooth, liquid and altogether pleasing. Neil Young is now also onboard with the Plangent Process.

According to Ludwig in an interview published on backstreets.com, Springsteen heard a Plangent Transfer of Darkness at the Edge of Town and was sufficiently impressed to lobby for its use on a catalog-wide re-mastering project surely not primarily with a vinyl box set in mind.

In our world, a reissue project like this would be welcome news, though no doubt more welcomed cut directly from the original analog master tapes—scrape flutter and all. My experience and probably yours is that no digital transfer of an analog tape is transparent to the source. Something happens in the process that alters the sonic outcome—particularly in terms of transparency, spatiality and transient speed and articulation.

However, to paraphrase former Secretary of Warmongering Donald Rumsfeld, “You go to the lathe with the source you have, not the source you might want or wish to have at a later time.” Likewise, you will go to these reviews with the reviewer you have, not the reviewer you might want or wish to have at a later time.”

Greetings From Asbury Park

Most of this album was cut in a week at 914 Sound Studios a budget venue in Blauvelt, NY, a small Rockland County town between The Hudson River and The Palisades Parkway just north of the New Jersey/ New York border. The idea was to save as much as possible of the Columbia Records advance money.

The studio was owned by the noted recording engineer Brooks Arthur, who previously owned Century Sound Studios in New York City where Van Morrison recorded the magical-sounding Astral Weeks. 914 Sound Studios was somewhat of a more plebian venue.

The reaction at Columbia Records was mixed. Clive Davis said there were no singles and insisted that Springsteen record a few. The opener “Blinded by the Light” and “Spirit in the Night” were added while other tracks were bumped.

The record, released January of 1973 didn’t sell well and neither of the singles charted but some critics were impressed.

I bought a copy but ended up trading it in. I didn’t respond well to that album beginning with “Blinded By the Light”. I heard the recently released Doobie Brothers song “Listen the Music” in the opening riff, too much Van Morrison in melodies and clunky Dylan in the wordplay (“drummers” “bummers” “summer”, “dumps”, mumps”, “pumps”, etc.). Worse, I didn’t hear rock’n’roll in those grooves. I heard folk and Broadway.

Watching the Beatles and Stones ascend with cool reserve, Springsteen’s rise seemed calculated. Perhaps that’s because in 1964 at 17 I didn’t see the string pullers that in 1973 were easy to spot. Plus this was “next gen” stuff. Compared to The Velvet Underground this sounded like hyper-dramatic Broadway show music.

When you’re a kid, you feel as if you own the musicians you love and resent the ones you don’t. I didn’t “get” Bruce so man, did I have a chip—not as big as the one New York Times critic Robert Palmer (not the late British singer) had against Billy Joel.

Palmer wrote a Joel concert review in the Times that was so scathing and personal even a non-Joel fan like me cringed and felt bad for the guy. Wrote Palmer: "He has won a huge following by making emptiness seem substantial and Holiday Inn lounge schlock sound special . . . Yes, Mr. Joel has written some memorable pop melodies. Yes he's an energetic, flamboyant performer. But no, this listener can't stand him . . . He's the sort of popular artist who makes elitism seem not just defensible but necessary." Yikes!

Heard all these years later (and not once in between to be honest with you) my bad for judging the record by rock’n’roll standards acquired during the early to mid-sixties. Still the record is more Meatloaf than Jerry Lee Lewis and more Broadway than rock’n’roll. Nonetheless also in retrospect it’s clear I missed and/or didn’t appreciate the audacity and originality hiding in plain sight amidst the obvious and clearly recited influences. I probably tuned out before “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the the City”, which is both powerful and must have left the 20,000 or so fans who bought the album wanting to hear more.

Sonically the record still sounds just like the budget production it was. There’s nothing distinguished about its demo-quality, closely-miked sonics that includes what sounds like a booth-smothered drum kit splayed across the soundstage—you can almost imagine the egg crates lining the back wall (I’m not saying there were egg crates used as acoustic material, just that it sort of sounds that way).

I borrowed from a friend an early but not original pressing mastered at “COLUMBIA NY” and compared it to the reissue. The vague imaging and overall hollow vocal tonal balance of the early pressing is evident on the reissue, neither of which does well with the volume turned up too far but overall I think the new reissue improves upon the original particularly in bass articulation and a less cardboard sounding kick drum. Ludwig’s re-mastering is not revisionist and that’s good.

The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle

The follow up also recorded at 914 and released September, 1974 is musically all over the map just like the cover artwork. On the cover we get a pensive, concerned looking Springsteen as urban sophisticate in place of the impish grinning one on the first album’s back cover “postage stamp”. But turn the record over and it’s a purposefully washed out looking “smile for the camera” photo of a goofy Jersey Shore band.

“The E Street Shuffle” is an exuberant three-part, tuba anchored stage show, soul review opener that somehow always reminds me of “Ode to Billie Joe” performed by a Motown act but then Springsteen follows with the evocative Jersey Shore ballad “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)” that’s a great song about both a town and a relationship in disrepair but much in need of a more effective delivery. Springsteen nails the talking parts but swallows the chorus. The Hollies version nails it IMO.

“Kitty’s Back” sounds like warmed over and weak Allman Brothers minus the guitar anchor. It goes on for way too long and what would obviously work well on stage is less captivating on record.

The Dylanesque epic “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” ends the side with an effective acoustic guitar lead and overdubbed mandolin and harmonica from Springsteen and probably too much tuba. It’s Springsteen operating from the margins and seeing both the romance and isolation of life on the road.

Side one is a musical mash-up that lacks focus but something magical (finally) happens on side two. “Incident on 57th Street” grabs and holds in way that for skeptics and less than true believers, all that came before did not. It’s the excitement of the city for a suburban kid wrapped in vividly drawn “West Side Story”-like characters.

“Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” seals the deal as all of the seemingly disparate elements that would come to define Springsteen coalesce into a believable, joyful mess of ascending keys, Latin showbiz horn shtick, repeated background choruses and finger popping, youthful, high-stepping, ecstatic delirium. You didn’t have to see Springsteen live to know how well this would play on stage.

The closer “New York City Serenade” sounds as if it was imported from a different record and performed and even engineered by a different team. The sound is far better focused, the open spaces better delineated and even the instrumental harmonic structure improves.

David Sancious’s piano moves from cocktail lounge noodling to jazz-trio land to piano concerto grandiosity that’s over-the-top ornate for rock’n’roll (much like Mike Garson’s playing on Bowie’s Alladin Sane), but at this point it’s all too obvious that Springsteen will not to be constrained by rock’n’roll’s conventions. Side two is arguably the single best side of Springsteen—as close to a coherent suite as he’s put together on an album—and it well argues for the album format as well as for the The E Street Band. You leave the side transformed and transported.

Here I compared this reissue to a later pressing but one with the “RL Masterdisk” stamp and if the original is in any way similar to the one I listened to, the new reissue is a mixed bag of improved bottom end extension, punch and articulation and a somewhat less expansive soundstage and less overall transparency.

The reissue’s transient and sibilant articulation were also not quite as precise as the original’s but on balance I thought the reissue’s improved tonal balance and more solid bottom end foundation give it the nod. The original sounds hollow and boxy by comparison, the reissue far better balanced.

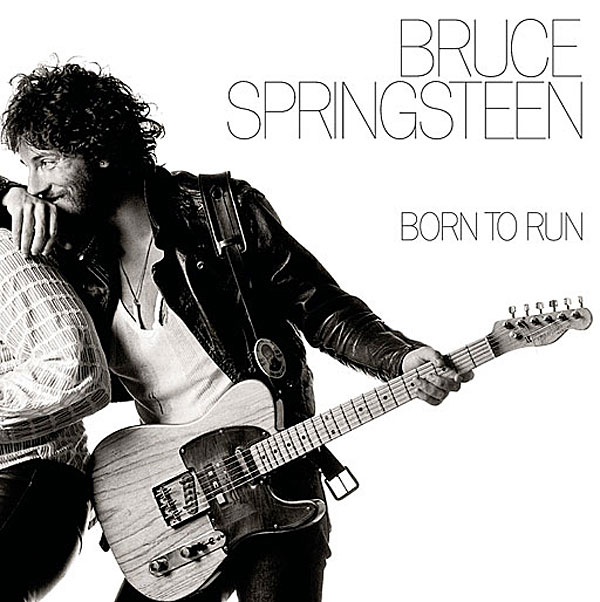

Born to Run

It’s not difficult to understand why this was breakthrough record issued in the summer of 1975 that made Springsteen a superstar from the dramatic cover photo to the musical mash-up of Americana (“Thunder Road”) and soul review where the “big man joined the band” (“Tenth Avenue Freeze Out”) and of course “Born to Run” which gave Phil Spector “Wall of Sound” chills to even the most skeptical Bruce watcher.

The song distilled everything Springsteen had been articulating: it had escape (on the streets), exhilaration and high drama but it also had forward propulsion, a direct thematic purpose and Springsteen wrote it in the first person instead of about characters he’d observed.

It was sort of “4th of July Asbury Park (Sandy)” on steroids but to help assure a mass market the record steered clear of too many direct New Jersey references in favor of more oblique ones. There’s a “turnpike” a “Jersey” and a “Route 9” (Springsteen probably didn’t want the original fans to feel abandoned and he was still writing about what was familiar) but for the most part the record is more universal and less regional.

The lyrics were well-focused on growing up and getting out and on love and betrayal—even the gay kind as some claim “Backstreets” is about (read the lyrics in that context).

While the album was the beginning of the Jon Landau era, “Born to Run” was produced by Springsteen and then manager Mike Appel and recorded at 914 Sound Studios before the move to midtown New York’s The Record Plant where the rest of it was recorded by a young engineer named Jimmy Iovine under Landau’s production direction.

Iovine of course went on to start Interscope Records and later Beats By Dr. Dre Headphones, which he and the Hip Hop star sold to Apple for oh, a zillion or so dollars, along with the Beats music streaming service, which Iovine had purchased from MOG and re-branded.

Born to Run was the first Springsteen album that was not a stage show review put on a meandering record. It was a collection of studio produced songs carefully sequenced and because Columbia was determined to finally break Springsteen into the mainstream it came up with the cash to give the artist as much studio time as necessary—more than a year—to get it right.

Both sides open with exhilarating escape songs and end with songs of loss and betrayal (I found a typo in the “Backstreet” lyrics: “lett” instead of “left”).

I once thought Classic’s reissue was really good but the sound mirrors the cover art: dark and closed in. The mastering scribe on Classic’s reissue says “LEC Gateway”.

According to Bob Ludwig, the Classic was cut at Gateway about a month before he sold the lathe. “LEC” is Lance E. Clark, who used to work for Bob. In any case, the closed in sound and the poor graphics can’t compare to the new reissue sourced from a Plangent processed tape digitized at 96/24, which is far more open (the glockenspiel is so much better), detailed and yes, more three-dimensional than the Classic reissue. I don’t have the Greg Calbi mastered original but you cannot go wrong with this Born to Run. It’s a complete success.

(The box set's overall sound rating would get a "7" were it not for the fact that these reissues improve upon the originals so the box gets a one number bump up, but none of these were great sounding productions to begin with).

End Part 1