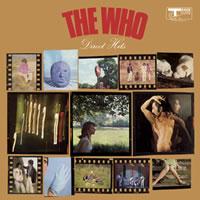

Part Two of McGill's Love Fest for Direct Hits Here

Part 2:

And also, bravo to you for remastering something PRIMARILY FOR ITS MUSICAL VALUES that could by no means be considered an “audiophile favorite,” but is so much more essential as music than any number of cheese “audiophile” reissues.” No doubt you’ll field a few silly complaints from people who don’t understand the limits of these master tapes. (Classic showed the same good attitude when they reissued the Munch “Saint-Saens Organ Symphony” [LSC-2341], which “has distortion on the master tape”… but hey Audio World, it’s the BEST PERFORMANCE of a great work, and sounds thrilling!)

A few words about the pedal point in “Substitute.” For non-musician readers, a “pedal point” is a drone bass , a bass note that stays steady while the chords change all around it, “tugging” against it. Whether you know what you’re hearing or not, your ear/brain want it to resolve. “Substitute” is the first rock song I know of to be built around this device; later instances abound. Punk fans may remember “Son of Sam,” from the Dead Boys’ We Have Come For Your Children. In the chorus, while Stiv Bators derangedly howls “I AM SON OF SAM,” the ominous chords rise and fall while Jeff Magnum’s bass stays stubbornly put… until the VERY LAST CHORUS, when he cuts loose and climbs all over said chords like a mad monkey, his ropey compressed tone commenting on the sick shrieks and sirens like low-pitched laughter. A moment of true tension release. On Jason and the Scorchers’ 1985 cowpunk masterpiece Lost and Found, a wonderful ballad/rocker called “Broken Whiskey Glass” milks a similar device. Each time the frantic momentum of the chorus collapses into a half-time section (“Here lies Jason…”), the chord changes are carried by Warner Hodges’s brilliant army of overdubbed guitars, while bassist Jeff Johnson hangs on a very low E (on “strangled by a love – that wouldn’t breathe”); then the second time Jason sings that line, Johnson’s bass climbs and slams and then descends with the guitars, to huge delayed-gratification impact.

And to enjoy a third and a fourth example of pedal point much closer to home: the chorus of “I Can See For Miles” is Pedal Point 101, as Entwistle bangs on a low E while guitars and vocal harmonies soar through magic rising chords. And switch that around backwards for “Won’t Get Fooled Again:” John Entwistle more-or-less (in his inimitable busy style, natch) follows Pete’s chords in the CHORUSES – but during the VERSES this time, he’s pedaling. Being John in 1971 now, he doesn’t just stay on one note; but he doesn’t follow the chords, he bases himself on a low A, dancing away and returning in regular runs up and down that have nothing to do with the “proper” chord sequence. (Joe Jackson’s hit “Steppin’ Out” similarly uses a pedal “riff” rather than a pedal “point,” with the keyboard playing that familiar unchanging “techno” bass melody under changing chords.) Back to “Won’t Get Fooled:” Entwistle finally yields and joins the acoustic guitar and keyboard that have been playing the chords all along (the electric guitar also joins in: it has been playing darting little riffs in the verses). It’s at the VERY END of the song, to explosive effect, right after “Meet the new boss…” (POW-POW!!!) “Same as the old boss!!” (POW-POW!!) Now THAT’S set-up and delivery!

Back on “Substitute,” Pete partly provides the pedal himself. The rhythm-guitar riff that opens the song and supports the choruses uses the chords D, A, and G against a continuing low D note on the guitar. Entwistle simply reinforces this when he enters, playing his own even lower D behind Pete’s part, only bursting into motion for the verses and bridges (and his bass solo of course, a very fat jolly one compared to the lean-and-snarling bass performance on the previous single “My Generation,” and here backed by Pete’s high ringing guitar sort of imitating vocal “ahh’s”). The only time we hear the main chordal riff in a “clean,” non-pedaled form is in Peter’s brief chordal solo 2/3 of the way through the song, where he enthusiastically plays a “normal” D-A-G-D progression, and then Entwistle comes pedaling in again on his D before Moon anchors/disrupts everything with a cathartic earthquake fill that has to be one of his most exciting moments on record. So in this song, the “release” from the pedal is not a different bass under those chorus chords as in some of the other songs mentioned, but simply those post-pedal moments when the song goes back into the verse and Entwistle can lurch into his fat Motown-style rumbling, underscoring Daltrey’s delivery of Townshend’s message of frustration and inability to either break out or surrender with a circular bass line that embodies striving through possible futility, going around in circles and wasting so much motion but exploding with endless potential, like an adolescent boy. Which is the point. Moon was 19 when this was recorded, the others just a year or three older. And The Who are the ultimate adolescent-boy music (many more male than female fans, ever notice?), at least until Led Zep came along. Speaking of which, listen to Entwistle’s angular blues riffing in the bridges (behind “I’m a substitute for another guy…”), and you don’t have to let your mind wander far to feel like that bass line could be from an outtake from “Led Zep I”! They really had it all, did the early Who.

There’ve been a lot of substitutes for The Who in the four decades since this stuff burst out, from the manic Moon-isms of the Pistols’ Paul Cook and the early Dash Rip Rock’s Fred leBlanc, to Thom York’s haunting Tommy-esque falsettos and haunting chords all over Amnesiac and other Radiohead delights. But it feels so good to get back to the originals, in some ways closer than ever before. I recommend this album, and all the other early Who you can get your hands on.