The Right Rite?

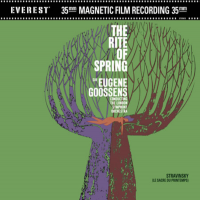

Fast-forward to 1959 when this recording was put to tape, or rather to 35mm film by famed engineer Bert Whyte. Everest, along with Mercury Living Presence were innovators in in the use of 35mm film for recording. The trend never caught on, but that doesn’t mean there were not serious advantages to the format, including increased dynamic range, a higher signal to noise ratio, and minimal wow and flutter. Here Eugene A. Goossens conducts the Rite with the London Symphony Orchestra. Goossens was very active in the mid-twentieth century as both a conductor and composer. He also was the brother of Leon Goossens, the most well regarded oboe soloist of the early 20th century. Goossens however, is most remembered today for a scandal in the mid-50s where he was implicated in an affair with Australian occultist Rosaleen Norton (dubbed “The Witch of King’s Cross”), a press scandal from which his career never fully recovered.

In the mid-2000s, Classic Records reissued some key 35mm titles from the Everest catalog, which proved how good the sound of the film stock was, and just how bad the original Everest pressings were at conveying it. These titles were cut by Bernie Grundman on his all-tube system at the time and released as 33rpm titles. However, Grundman also cut versions at 45rpm, which never received release until now. When Chad Kassem at Acoustic Sounds acquired Classic Records, he also acquired the metal parts for these 45rpm cuts, which have now been released by Analog Productions.

I own a few of these Everest reissues, both in their original 33 and 45 rpm iterations. The sound Bernie Grundman was able to coax out of these 35mm film reels is dynamic, vivid and breathtaking. This particular release is no exception. Bass drum hits and timpani thwacks rocked my listening room. Trumpet calls pierced through from the back of the convincingly-rendered hall, and the trombones menaced their way through the many climactic dance numbers that awaited them. Overall, the sound of this reissue is a sonic delight, determined to put your full-range speakers to the test. And not an overengineered one either I might add. This recording seems to lack the over mic’ing that plagued audiophile orchestral recordings in following decades (hello London Phase 4?). Unfortunately, the film appears to be stretched or warped in some way at the very start of the introduction, somewhat ruining the principal bassoons’ opening solo. There was also a bit of a recessed violin/viola sound, but it was difficult to determine if this was a recording issue or a performance issue, the latter of which are unfortunately common in this instance.

It’s strange to think about the fact that this recording was made in a time closer to the premier of this work than it is to our present day. I say this to point out that the Rite was considered astonishingly difficult when it first appeared, and although orchestras breeze through it nowadays, in the middle of the 20th century it likely was still considered a challenge. Back at the Manhattan School of Music, my Woodwind-Brass lab teacher, trumpeter Mark Gould once made a poor bassoonist play the opening solo a half step up in pitch, saying that the piece was “too easy” now, and everyone plays it too well. The goal was to make it hard again, as it would have been back in the day! But I digress…

The London Symphony Orchestra were certainly capable of greatness during this period in the 50s, the famed Dorati Firebird serves as a prime example. However, the performance here with Goossens at the helm suffers from strange artistic choices and some inconsistent playing. The “Augers of Spring” early on in the first part is almost anemic, and lacks any bite during the accented beats. In fact, if there is one overarching theme I can use to summarize this recording, it is primarily that it is too slow and dull in interpretation. That doesn’t mean there aren’t hints of greatness, however. The French Horns and Trombones all have stellar tutti features and sound at the top of their game, the concertmaster has some finely played solo sections, and the flutes provide a wide pallet of colors easily conveyed through the detailed soundstage. However, the orchestra is often held down by sloppy and out of tune playing from the rest of the woodwinds and strings that bungle their entrances, and for when it matters, a general tendency for the orchestra to not be entirely cohesive or together.

Perhaps I am being too hard on this particular performance, but if I am, it’s because listeners are blessed with a wealth of great recordings available, including on vinyl. From just one year earlier we have the excellent (and fiery) 1958 Bernstein/New York venture that was reissued back in 2013 in AAA sound cut by Ryan Smith, and the slightly more measured but equally excellent Solti/Chicago outing on Decca. If you have yet to own a copy on vinyl of the Rite of Spring, those are the two recordings I would recommend hearing first. However, if you already have one or two solid versions of this piece, it might pay off to give this audiophile edition a go, it is sonically better than either of the versions I mentioned, and it might provide a slightly different insight into a piece that has now become “standardized” both in the repertory and in terms of interpretation.

Michael Johnson is a Phoenix, AZ based oboist and audio writer. He is currently a member of the Tucson Symphony, and performs regularly with the Phoenix Symphony and Arizona Opera. He is a contributing writer at Audiophilia.com and maintains a vinyl-focused youtube channel by the name of PoetryOnPlastic. You can follow his vinyl journey on Instagram at instagram.com/poetryonplastic