“Ramblin’ On” About Led Zeppelin II Or I Got Blisters on My Eardrums!

For the mathlexic, that’s almost 45 years ago. So how ironic was it that at some point during Train’s Stern Show appearance, group leader and singer Pat Monahan mentioned Kisses on the Bottom (which he incorrectly called “Kisses on the Bum”), Paul McCartney’s homage to the formative songs the ex-Beatle grew up listening to?

Monahan incorrectly inferred from the standards album that McCartney was “out of touch” with what kids today listen to.

The album title is a line from Fats Waller’s 1935 tune “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter”.

The heart of the Lennon-McCartney writing genius arguably occurred between 1965 and 1968 or around 30 years after Waller sang a song written by Fred Ahlert and Joe Young.

So there was Monahan singing a 45 year old song complaining about McCartney singing one that was fresher in 1967 than “What Is And What Should Never Be” is today.

Does that make any sense to you? Maybe not. It does to me. Maybe to a twenty year old today, Led Zeppelin’s music sounds like what Fats Waller’s did to me when I was twenty, which was around the time Revolver was released. And I knew that song because we had a player piano and that was one of the piano rolls. It sure sounded ancient to me at the time. Ironically today it doesn’t sound quite as old.

These Led Zep reissues must not sound too old to a lot of people because as I write this, all three albums of really old music are on Billboard’s Top 10 album chart!

No doubt some oldsters are re-buying on CD hoping that they’ll sound better than the unpleasant-sounding 1993 CD releases, but clearly Led Zeppelin’s first three albums, forty plus years after first being released, have a younger generation’s attention.

I’ve been spending what might seem like way too much time comparing and dissecting various pressings of Led Zeppelin II almost 45 years after its debut as if it really mattered. Actually I think it does.

Perhaps “classic” rock from the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s is becoming like long enduring “classical” music except that only the original recording counts and the interpretations to be judged are not different performances by different orchestras and conductors but rather different masterings of the same material. The same might be said of jazz from that same era.

The judgment to be made is not merely about which “sounds” best, but rather about which best communicates the musician’s musical and emotional intentions.

Train’s appearance made me realize how different today’s music scene is than that of the era during which Led Zeppelin held sway. Monahan made no effort to hide his real self behind a mystery affectation like, say, “The Thin White Duke” or “The Lizard King”. He was honestly being himself. He wasn’t trying to build a wall or create a persona.

True, Stern has a way of breaking down that wall but Monahan wasn’t even trying to create one. He talked about his golf game. The only rock star I can recall from the previous age willing to admit to being a golfer was Alice Cooper.

I have it on good authority that Bob Dylan is an avid golfer but he doesn’t want anyone to know, so covetous is Bob of his image. Just the thought of Bob Dylan standing on the first tee with a driver in his hands seems wrong.

Dylan plays golf but he covers his head and tries to disappear on the course. I doubt you’ll hear him talk about his golf game any time soon. Today’s musicians could care less about maintaining an air of mystery. That’s too bad because that era was fun, particularly for adolescents wanting to fantasize about a different reality. Of course today’s kids can more easily disappear into video games.

The music today is similarly lacking in oversized personalities compared to back in the 60s and 70s. Where are the larger than life giants? Where are the virtuousi? The guitar monsters? The new legends? Other than John Legend, who is a nice guy and not much of a legend. What happened in rock also happened in jazz. Where are the larger than life giants like Monk, Miles, Coltrane, Art Blakey and Mingus? There are none. Where are the guitar greats? The saxophone colossi?

There are very good jazz musicians and some very good rockers like Jack White but most are almost annoyingly introspective and purposefully smaller than life. Are there any like Page or Plant? Or even David Lee Roth? Or Monk? Or ( insert your fave here). Not really. Lady Ga Ga had it sort of going for a short time.

Which helps explain why Led Zeppelin still matters not just to aging boomers, but to young people looking for some musical entity bold, brash and big to look up to and get excited about.

Led Zep was a band of enormous gestures in an age of big ones. The name says it all: it was heavy, but it could soar. The group lifted a lot but made it their own (including for a while taking credit for songs they didn’t write).

They combined blues with rock, with folk, with psychedelia and with cartoonish, misogynist sex at a time when sexually cool hippies years before had rejected as “sexist” their brand of swagger once previously popular in the ‘40s and ‘50s. It’s why Elvis became not at all cool only to become so again after his death.

At a time when it was PC properly said as “let me caress your breasts”, Led Zeppelin was saying “Let me cop a feel off your titties, bitch!”

“You need coolin’ I ain’t foolin’” could just as easily have been sung to a car as a woman. In fact, the next gen’s Led Zep, AC/DC, sang “Shook Me All Night Long” (“She was a fast machine/She kept her motor clean) as if it was about a car. Queen’s Roger Taylor dispensed altogether with metaphor by singing “I’m in Love With My Car”—and he meant it!

The music on Led Zeppelin’s debut album can be heard as being drawn from Jeff Beck’s Truth album, arguably the first “heavy” album but by the second one, it was obvious that this band was riffing into the future with future proof swagger.

I chose to cover the second album first because for record collectors, it holds greater interest. There’s the legendary Robert Ludwig first cut that was quickly withdrawn from the American market, supposedly after it proved too hot a cut for Ahmet Ertegun’s daughter’s turntable.

There’s the equally legendary “plum label” UK original. It’s important to remember that though they were from the UK, Led Zeppelin was first signed to American Atlantic Records, which is why the original UK pressing says “Under License From Atlantic Records Corp, USA, Manufactured by Polydor Records Ltd.”.

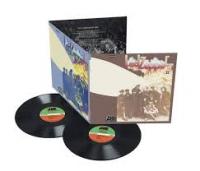

Sitting here comparing the new reissue cut from 96/24 files with two original (but not RL) pressings, with the original “plum label” UK release, with a later WEA orange/green reissue, with the 2001 Classic Records reissue, with an 80’s era Japanese pressing, not to mention the execrable 1993 CD remaster and with 96/24 files can make one question one’s sanity and/or produce a “what the hell am I doing with my life?” moment.

Once you do the work though, the importance of it becomes clear—that is if you think the music is important, and I do. It’s clearly stood the test of time judging by the chart action and by how much fun it still is to hear, especially since the blues, once a pop staple (as opposed to Pops Staples), has been drained from today’s radio fare. Salacious fun has been replaced by mechanical, puerile sex

Hell, there are people who day in, day out sample wine, coffee, olive oil, you name it, the same way some of us sample pressing quality. This is no more or less important, particularly for people who love listening to recorded music.

So here’s what I did: first I played the new reissue straight through and rather than dissect it, I just let it wash over me at high SPLs. That’s what a big-ass, full range system is designed to do and that’s how I listened. And then I judged the experience without prejudice, though I had a pretty good idea of what the other versions would deliver.

Look, there are few albums in my collection that feature the kind of gross overload distortion obvious on this master tape (one would be Bill Evans’ and jJim Hall’s Undercurrent). I don’t think it was an accident. They wanted to push the limits and they did. They wanted a big-ass drum sound, searing, crunching guitars and psychedelic sound effects rivaling Hendrix’s (which Kramer also created) and they got them, but where the big dynamics should have dug in and taken the ride to Pike’s Peak, on this album they hit the wall and went into overload.

It’s important in this discussion to remember the tape’s age. It’s been more than a decade since Bernie Grundman had his go round and ten plus years in the life of a forty plus year old tape is a long time. We don’t know the tape’s condition either physically or sonically.

“Whole Lotta Love” immediately made obvious this reissue’s smooth frequency balance. That’s probably to what Page and Metropolis mastering engineer John Davis paid most attention.

The reissue on vinyl seemed to be a linear and honest accounting of a very familiar album. Nothing “stuck out” in a negative way. It didn’t sound like it had been cynically EQ’d and that was positive. At first I found myself saying “This has the smoothness and drive of a master tape.” I was impressed, though the spatial presentation seemed meek, particularly during the song’s “orgasmatron” break. The spatial swirling and what sounds like manual tape drag across the heads yielded only a small amount of the familiar three-dimensionality and spaciousness found on AAA releases. The individual cymbal hits in that psychedelic break lacked sparkle and the familiar precision-crackle. The whole event lacked mystery and then when Bonham machine guns the drums ending it, instead of an interruption eruption the changeover was anything but abrupt.

On “What Is And What Should Never Be” it became apparent, even without comparing to other versions, that the song’s overall musical intent wasn’t being fully communicated. That’s something tied as much to feel as sound, though the sound was tonally well balanced but spatially mashed together and lacking in detail delineation.

You can barely make out the flanging effects on Plant’s voice.

Again, the break lacks drama. It begins with that menacing, growling Page guitar lick eruption that should send shivers but just doesn’t. It doesn’t even erupt.The bass line was homogenized and the attack softened. Textures sounded bland.

Microdynamic gestures—very familiar ones—seemed to have been lost. This is a song recorded with an almost impossible amount of overload distortion that usually tears up the song’s fabric for the better but here it seems to have been patched up and smoothed over. The album’s grit and edge seemed worn down.

Switching to the Classic Records 180g reissue from 2001 produced “shock and awe”. I also have the 200g reissues but the 180s were good enough!

Classic claims to have mastered from the original two track tapes, not the EQ’d production master, which I assume is also what Davis and Page used (to be clear I mean the original not EQ'd production master), but these two masterings could not sound more different.

The Classics, mastered by Bernie Grundman, produce so much more detail and resolve so much more information, so much greater sense of three-dimensionality you almost wonder if both are sourced from the same tapes.

Grundman claims to have used very little EQ per Page’s advice, feeding the signal into a Haeco stereo tubed cutting amplifier driving a Westrex cutter head on a Scully lathe. Two things were immediately obvious: either the Classic’s top end had been jacked up somewhat, or the new reissue’s had been tamped down to produce flatter response. Or the tape’s top end has further receded into the magnetic ooze from whence it originally came.

In some ways I better liked the reissue’s smooth spectral balance but I much preferred the Classic’s enormous three-dimensional soundstage, far greater overall detail and especially its transient clarity that I didn’t think was caused by the slight high frequency lift. Instrumental separation was far superior as were instrumental timbres, especially (ironically) Page’s guitars, which go from bone crunching to gossamer, from hell to heaven and back on the Classic vinyl but are homogenized on the new reissue. Compare his solo on “Heartbreaker” on the new reissue with the one on the Classic reissue. One’s floating in greater space and has transient detail to spare. The other sounds good but doesn’t “sear”.

Here are two short 96/24 excerpts of the "Heartbreaker" guitar solo. One is the current reissue, one the Classic reissue. Do you prefer one over the other? If so please comment (give the files sufficient time to load).

Page shortchanges himself in my opinion with this mastering but more so John Paul Jones’s bass work. The extension is great—better than on Classic’s take— but textural details get lost and transient definition blunted.

Bonham’s work takes the greatest hit on this record though. When Bonham hits the cymbals harder you hear it on the Classic reissue. All of Bohnam’s microdynamic intent is communicated. On the new reissue the small dynamic differences that communicate intent blend into one level, quelling musical excitement. The cymbal’s shimmer and ring on the Classic losses its metallic edge on the reissue, though which you prefer might be system dependent. You get the picture.

Moving on to the legendary “plum label” UK original, finds a tonal balance that’s more similar to the new reissue than to the Classic reissue. However, the plum label original shares the Classic’s three-dimensionality and air, its transient excellence and its macro and microdynamic detail. Plus it has the new reissue’s ballsy bottom end but with greater definition. Its legendary status is well-deserved! Surprisingly, the later WEA orange/green pressing, which is a different mastering altogether shares much of the plum label’s greatness.

Forget about the ‘80s Japanese pressing (Warner-Pioneer P-10101A). It confirms my suspicion that many Japanese pressings of that era were cut on systems using 8 bit digital delay lines instead of preview heads. It’s flat and dead and decay is cut off at the knees.

The original CD mastering done by the late, great George Marino with Page supervising back in 1990 is basically unlistenable. Clearly not Marino’s fault. He was great. The problem was with converters of that time. It’s sad and hilarious to read on Amazon.com the praises of this mastering. It’s unlistenable especially if you try to turn it up. And if you can’t turn up Led Zeppelin what’s the point?

While we’re in the digital domain, if all you own are those CDs and you live in the digital world, do not hesitate to buy this as a 96/24 download. It sounds so much better than the original CD you’ll think you’re listening to a different recording, not a different mastering.

The post RL American original (1841 Broadway label) is not worth the vinyl it is pressed on. When Ahmet Ertegun ordered it recut, whoever did the deed slammed it hard. It’s dull, dynamically compressed and just a waste. It’s to be avoided! If that’s your reference, you have no idea what this recording really sounds like! Any reissue other than the Japanese will do.

I did get to hear an “RL” pressing last year at the home of Atlantic Records CEO Craig Kallman, who is easily the most dedicated vinyl fanatic probably on this earth. I think he’s got upwards of 750,000 records. Of course the RL crushed the original. It is worth whatever it costs for you to get one, if this record means that much to you.

The Deluxe Edition’s Second Disc

The second disc in the deluxe set contains rough mixes, backing tracks, and other sonic ephemera. The first thing you’ll notice is how much better sounding the opening mono work track of “Whole Lotta Love” is to the final version. It’s not even close! Otherwise the sound is good studio demo quality. If this is the best they could do for outtakes and unreleased, clearly the band didn’t waste time in the studio. You won’t learn much and it’s hardly necessary unless you are a Led Zeppelin fanatic.

Shades of Brown

The packaging is okay. What is the correct shade of brown for the cover? I have no idea. Every version has a different color brown. The English covers are dark. The plum label cover has no blue in the clouds and a yellowish sepia toned photo. The second UK pressing has blue clouds and greater contrast in the photo. The original America pressing has the best cover: nicely textured heavy stock, a coffee brown, blue clouds, and pleasing sepia balance (are you barfing yet?). Both the Classic and Japanese are close to the original American. The new reissue’s cover is very pale and inexplicably features a different rear cover that uses the front cover but tinted with blues and greens, thus breaking up the original’s front to back cover flow. Go figure.

Conclusion

The overall tonal balance of this reissue is probably as honest a rendering as you’ll hear. It sounds similar to the “plum label” original, so tonally it gets an “A”. Spatially and dynamically it gets a “B-“. The picture is rather flat, space is limited and I’d say some dynamic compression was applied. If not, it sure sounds that way. In terms of overall detail and transient precision it also gets a “B-“. However, compared to the 1990s CD it gets an “A”.

I also listened to the 96/24 download and if you live comfortably in both the analog and digital words, I’d buy the downloads and don’t bother with the vinyl, though it's very well pressed at Pallas. There’s little difference sonically between the files and the record. Don’t kill me for writing that.

That said, if this album is somewhat important to you and you just have to have vinyl, this reissue is good. On the other hand, if this record is really important to you, find an RL original, a UK “plum label” original, or even a UK WEA orange/green later pressing or the Classic Records reissue, but if you choose the Classic be prepared for a tipped up top and less than muscular bottom. However, the rest more than makes up for the truncated bottom end!