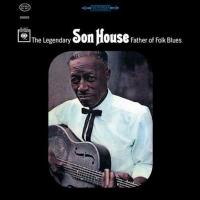

Son House’s “Father of Folk Blues” Provides A Uniquely Intimate Listening Experience

Naive and inattentive listeners can lump House into the wide array of blues artists musically active in the 1920’s and 30’s Mississippi River Delta, but House’s recordings are unique in their amazing complexity. Instead of fingerpicking or playing with a pick, House slams the strings with his fingernails and fingertips in a sometimes aggressive yet graceful way. His voice is often rough around the edges, but this is the sound of a man playing for individuals who will listen and understand, not a man looking for wide commercial appeal.

Father of Folk Blues recorded April, 1965 in New York City opens with “Death Letter,” in which House tells the story of waking up one morning only to find a note revealing an unknown lover’s death. “I found a letter this mornin’, how do you reckon it read?/It said ‘hurry, hurry, yeah, your love is dead’/Looked like there was ten thousand people standing round the buryin’ ground/ I didn’t know I loved her ‘til they laid her down.” Parts of the song, especially the first two lines, lift from House’s song “My Black Mama Pt. II,” recorded in August 1930 for the legendary Paramount Records in Grafton, Wisconsin. Despite its relatively simple chord pattern (played in open G tuning) and structure, “Death Letter” tells a complete narrative with House’s singing dynamic and expressive. The song has since become a standard covered by the likes of the White Stripes, Johnny Winter, and Cassandra Wilson.

Other highlights of the first LP in this 45rpm set include “John The Revelator” and “Empire State Express.” In fact, every song on this record is a highlight but I won’t list them all! The former, a traditional gospel tune, showcases House’s vocals extremely well as he’s accompanied for the 2.5-minute duration of the song only by his own handclaps. His vocal range isn’t all that wide, but the passion of his performance more than compensates. “Empire State Express” is a unique track on this record in that it’s the only one with two guitarists; Al Wilson of Canned Heat plays alongside House, creating intricate interplay between the two. (Wilson later shows up on “Levee Camp Moan” playing harmonica.)

Side two (or on this 45rpm set, disc two) begins with House revisiting a selection from his past repertoire. “Preachin’ The Blues,”originally recorded in two parts for Paramount Records, appears here re-recorded and renamed as “Preachin’ Blues.” It’s followed by “Grinnin’ In Your Face,” the second song on the album where House is backed only by his clapping as he sings the refrain “Don’t you mind people grinnin’ in your face/You just bear this in mind, a true friend is hard to find.” Later, he sings about how “just as soon as your back is turned, they’ll be trying to crush you down.”

The nine-minute “Levee Camp Moan” concludes Father of Folk Blues. (This 45rpm set from Analogue Productions adds as a bonus track a rendition of the traditional “Motherless Children” not found on standard 33 ⅓ RPM editions. Here, House’s guitar is complimented by Al Wilson’s harmonica, which appears in between the former’s lyrics. The song tells the story of a man who loves a woman who doesn’t love him. The woman is disappointed when the male narrator can’t afford to buy her things until he leaves her, but he still can’t help but think about her. House’s first line in the second-to-last verse sums it up appropriately: “It’s so hard to love someone when they don’t love you.”

Following the recording of this album, House played several concerts, including the 1965-66 Newport Folk Festival and he toured from 1967 to 1970. One winter night in the early 70s, House fell on a Rochester street and suffered frostbite damage to his hands that limited his playing ability. His last show was at the Toronto Island Festival in July 1974. A couple of years thereafter, he moved to Detroit, where he lived with his wife and her three grown kids until he died of larynx cancer at age 86 on October 19, 1988.

AP’s reissue of this recording is extremely transparent, naturally balanced, and fulfills the “it’s like he’s playing in my room!” audiophile cliché. The record sounds mono at times, but that is how the album was originally mixed. Some reissues of this album such as The Essential Son House CD compilation use an alternate mix with a wider instrument pan that separates House’s voice from his guitar. Here, Ryan K Smith used the original two-track stereo tape from the Sony archives and referenced an original Columbia “360 Sound” pressing to master this correctly and it shows. Never have I heard a blues recording that is so musically raw yet so sonically exceptional. Further, the QRP-pressed platters are silent and flat as pancakes.

The packaging here is also top notch, with additional essays and pictures from the 1992 CD reissue lining the Stoughton gatefold’s interior. In addition, the reproductions of the Columbia “two-eye” label from the original release’s time are excellent. For fans of early blues and music in general, I can’t recommend this reissue enough.