This release very much sounds like a case of the medium taking precedence over the message. I'd rather enjoy the interpretations of this music by true "Bach-kenners" rather than an audiophile version by a non-specialist performer (I'm trying to choose my words carefully here so as not to offend). When most self-respecting cellists worth their salt have recorded these works (some many times over) we don't need another run-of-the mill version even with superlative sound as there's no point if you aren't going to listen to them more than once.

BTW Robert Schumann also provided an "improved" version with piano accompaniment of that other Bach instrumental monument, the Chaconne from his Second Violin Partita.

Tastes and values were different then!

Chasing the Dragon Tackles the Bach Cello Suites

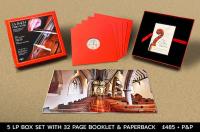

In view of this excellent track record, I find no pleasure in reporting that CTD’s most recent endeavor takes all risks and suffers all consequences. This new vinyl-only limited edition of Bach’s Cello Suites raises eyebrows on two counts: the lavishness of the presentation, including five LPs instead of the usual three, and the $689 price tag, which comes to $137.80 per disc before tax and shipping! Reading CTD’s promotional literature one gets the impression the priorities are presentation, production, and personnel, more or less in that order. The 32-page oversized booklet is given over to so many photographs of instruments, venues, artsy shots of microphones, record grooves, tape heads, tape reels, meters, and cutting lathe, plus a long-lens closeup of Nordost cables, that an unwelcome note of audio fetishism is sounded. Add to these the photographs of musicians and technicians working or relaxing, and the whole thing begins to feel like a scrapbook for a vanity project.

What text there is, a mere four-and-a-half pages of large type with plenty of air between the lines, consists in just a single page devoted to the suites and telling us almost nothing about them in actual musical terms (though it does include an anecdote about a knife fight Bach got into as a young man). The apparent justification for such parsimony is the inclusion of Eric Siblin’s “The Cello Suites: In Search of a Baroque Masterpiece”, a fascinating book full of valuable information, but principally about the author’s personal discovery of the music, its origins, its history, and how it came to be unearthed and popularized by Pablo Casals. About the suites’ strictly musical forms and contents, there is little, none of it locatable via the index. Audiophiles coming to the music here for the first time wouldn’t even learn that these are dance suites in which Bach enlarged the various forms beyond anything previously imaginable. And in an almost unbelievable oversight—at least I assume it’s an oversight, since if a conscious decision, it was a boneheaded one—neither in the booklet nor on the box is there any list of the suites by number and movement, with timings, and how they are distributed over the five LPs except on the disc labels themselves. Initiates won’t know they’re listening to an allemande, a courant, a saraband, or a gigue unless they use their smartphones to snap a shot of the label before returning to their listening chairs.

Before getting to the performances, let me say that the sonics are absolutely superlative, truly reference standard by any measure, notably for transparency and that elusive sense of lifelikeness, tactility, and dimensionality, the microphone placement ideally mediating focus on the instrument while capturing the warm ambience of the settings (two rural churches in England because Covid forced the project into hiatus): Peter Walker’s “window onto the concert hall” achieved to a fare thee well. I’ve never heard a more beautiful and convincing recording of any instrument and only a tiny handful as good. Processing is likewise excellent, surfaces silent except for the stray pop or tick rearing their unwelcome heads.

Why two cellists, a pianist, and five LPs when three normally suffice? Justin Pearson, the principal soloist, plays only the first five suites; the sixth, which Bach wrote for a five-string cello, is performed by Pedro Silva. (Most cellists either transpose the work for their four-stringed instrument or learn to play the five-stringed variant.) As for the pianist, there is a bonus in the form of the only surviving suite in Robert Schumann’s arrangement with piano accompaniment, the third (hence the additional pair of LPs, with the fourth and sixth suites spread over two sides each). I listened once to this curiosity and will do so never again: Schumann or no Schumann, it’s the equivalent to trying to improve the Mona Lisa by painting a necklace on her. As to the cellists, I’ve never heard of Silva before, but Justin Pearson is a musician of high and myriad accomplishment: Principal Cellist and General Manager/Artistic Director of the UK-based National Symphony Orchestra, Guest Principal cellist of the Royal Philharmonic, and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s go-to soloist. He’s recorded previously for CTD, notably with the chamber ensemble Locrian, which he founded; and he’s also recorded for several non-audiophile labels such as Naxos, Hyperion, ASV, Dutton, and Carlton Classics.

These suites are my wife’s favorite music, with nine recordings in our library. Time waiting for the review set to arrive was spent boning up on them, to which I added at least as many more through Qobuz and Tidal. This may have been a mistake, because never once was any suite or movement in the CTD box flattered in the comparison. Not that the performances are bad—on the contrary, they are good, often beautiful, and more than adequate to convey something of the measure of the music. Pearson and Silva are plainly musicians of taste and intelligence. Their performances here are conscientious, typically moderate in matters of tempo, dynamics, and expression, with nothing that could offend.

But therein lies the rub—nothing offends, but very little excites, thrills, electrifies, or moves. To my ears, these performances are inhibited by the kind of restraint and reserve that results in a lack of personality, character, intensity, passion, and that difficult-to-define but easily felt sense of personal investment, conviction, and imagination which raises competence to excellence and excellence to something like transcendence. I wonder if one of the reasons is the fact that the recordings were made with unbroken takes and no editing. As is not the case with the recordings by Interpreti Veneziani Chamber Orchestra or Clare Teal and company, this has not made for greater abandon, excitement, and intensity. Rather the opposite: the overriding impression is of prudence, caution, carefulness—above all, a mistake must not be made, or we’ll have to start all over. (Why? The booklet suggests these were recorded on analog tape, not direct-to-disc, with high-resolution digital backups, including DSD.)

As I hear it, Pearson’s general approach is to set a certain basic level with respect to loudness—the scores contain no indications of dynamic contrast or change of tempi—from which he deviates little as regards dynamics, rhythmic inflexion, and expressiveness, with little tonal light and shade or plasticity of phrase. This results in a sameness of tone color from movement to movement and suite to suite that over the long haul begins to feel a tad monotonous. Owing to the sound of his five-string cello, Silva’s performance of the sixth brings some tonal variety to the proceedings, but his rather dour interpretation might leave you baffled as to why Rostropovich called this suite a “symphony for solo cello.” (Where are the joy and triumph?)

Slower movements work better here than the faster ones, which often lack lilt, rhythmic pointing, and where needed drive, a particular liability in the paired minuets, bourrées, and gavottes that Bach inserted between the sarabands and the gigues in each of the suites. The performance I like most is that of the second, which some scholars speculate Bach wrote in response to the death of his first wife. Here there is no doubting Pearson’s depth of response, which suggests less Whitman’s lilacs blooming in the dooryard than Dickinson’s formal feeling after the great pain of loss. Otherwise, there is nothing that challenges the many distinguished traversals in the catalogue, notably those by Casals (EMI), Queryas (Harmonia Mundi), Gerhardt (Hyperion), Ma 2 and 3 (Sony), Van Linden (Harmonia Mundi USA), Schiff (EMI), and Starker (I prefer the later RCA to the Mercury).

If this sounds unduly harsh, my reply is threefold. One, it would surely be condescending to apply standards other than what is applied to any release of this or other music. After all, several recordings from CTD’s catalogue have been suitably recognized for high musical as well as sonic excellence, including the two referenced earlier in this review, to which I would add the really terrific performance by John Lenehan and the Locrian Ensemble of Beethoven’s “Emperor” concerto (which is also the finest recording-qua-recording I know of this work). Two, among the first concerns of this journal must be the readers, not the objects or subjects under review. Which leads directly to three: that pesky matter of value that refuses to be shuttered. Even were I more enthusiastic about the performances, I would have a hard time getting my mind around the price of this set. There are at least four big CD boxes that contain practically every note Bach ever wrote that survives, in performances at least good, typically excellent, and sometimes at the highest levels, available on Amazon and other sites, priced from $130 to $495, along with innumerable sets of these six suites by the greatest cellists, in beautiful sound that will set you back not much more than the cost of a cocktail or two. Yes, yes, I know—compact discs, not vinyl—digital, not analog. Who cares? They are Bach, and not just Bach, but all of Bach. Beside such treasures, this CTD box reminds me that one of the meanings of lavish is to “spend wastefully.”

Paul Seydor is a California-based film editor, author ( "Peckinpah: The Western Films--A Reconsideration") and contributor to The Absolute Sound magazine. He also loves dogs.

- Log in or register to post comments

Since you mention two of his three recordings as part of the canon, I have to tell you how much I hate Yo-Yo Ma's Bach Cello Suites. He overemotes (like he always does, but here it ruins it), making the recording all about him. (Whatever the tinnitus equivalent of vibrato is, I always have that in my head after I'm subjected to Yo-Yo Ma.)

My favorite BacH Cello Suites recording hands down is the Jaap ter Linden, which is from the late '90s. Second is the János Starker, from the '60s.

Love the ecumenism! And insightful as always, if in this case the bearer of bad news.

Don’t agree at all with Andy on Yo Yo Ma. I think his most recent version - available on vinyl - is beautifully done, not at all self-indulgent. But as PS indicates, there are plenty of options, starting with Starker. Have to agree on preferring his digital RCA to the Mercury available in multiple fine vinyl versions, as discussed previously by MF.

"Chasing the dragon" is slang for smoking heroin.

Sometimes also used for free-basing cocaine.