Analog Corner #35

(Originally published in Stereophile, June 12th, 1998)

How was your month? Mine was analogo bizarro.

But before getting to this month's promised story—my visit to the Library of Congress—I have to clear the deck: I received an e-mail from an individual, fairly well known in the grooved world, telling me that I "may not have had all the information" when I wrote in my February R2D4 that Alto Analogue's Ataulfo Argenta Edition (AA006) boxed set was mastered by Nick Webb at Abbey Road from the original analog master tapes.

That's what was claimed in the set's booklet, and what was told to me by the producer. But according to this individual, "The Alto set of Argenta was not issued from original master tapes, nor was the final product mastered at Abbey Road."

That's a pretty serious charge, don't you think? He went on to say that "There were problems with the mastered originals [the metal masters I believe], so, in Germany, copy tapes were used for the final production issues. Also, the recordings, while very upfront-sounding, were also digitally processed."

Look, compared to Yeltsin's firing his government, or the upcoming attempted right-wing coup d'état over some alleged BJs (or the dastardly "coverup" of same), this isn't much of a story. But in our little analog corner of the world, it is. I don't like being snookered, and I don't like passing bad info on to you.

Get the picture? So after responding to this individual with "Unless you can back this up with factual information, you ought to be careful what you say and write," and after getting a response which was basically hearsay and innuendo, I called Alto Analogue principals Ying Tan and Joachim Böse to confront them with the charges.

Now, normally, when I receive information from an individual who has a published byline, as this individual does, unless I'm specifically told that something's being passed on to me in strictest confidence, I assume it's on the record.

Wrong, Watergate Breath! When word got back to this individual that I'd actually used his name in relating the charges, he came back with, "Disregard anything I said to you today. It was all sheer fantasy. You ought to be ashamed of yourself. You're on your own on this one. You'll get no help from me....I am just shocked at your lack of professionalism."

I'll leave it to you, "Analog Corner" reader, to decide if I should be ashamed of myself, or if my naming names was unprofessional, but my attempt to get the facts certainly wasn't. One of the stories going around (and it is going around; a very well known, once-powerful audio writer volunteered to me at CES that the Argenta set was "digital'') is that there was a problem with the Abbey Road–cut lacquers that went undiscovered until the plating process in Germany. The cost of flying the hand-carried tapes back to Abbey Road from Spain and recutting them was deemed to be too great, so copies of the tapes were made and flown to the Pallas pressing plant (the premier German pressing plant, equivalent to America's RTI), where they were used to cut new lacquers. Since Pallas' playback decks (the story goes) don't have analog preview heads (Footnote 1), the signal had to go through a DDL (digital delay line) and therefore was "digitally processed." In a system without a preview head, the signal must be electronically delayed to give the lathe's computer a chance to make the change. Ironic, isn't it? The computer gets analog, the cutter head, digital.

Those passing this story along claim that the sonic effects of the digital delay line are easily audible on the boxed set. (An alternate version has the problems occurring in the plating process, necessitating the same scenario.)

Tan and Böse admit that there were problems with the plating and that a second pass was required, but they vehemently deny the allegations of tape copies and digital processing. While the issue is moot—the boxed set is sold out (dealers may still have some)—Alto's credibility and honesty have been called into question. That is a very serious issue for anyone in the reissue business—or in any business, for that matter.

I received two pieces of evidence corroborating Alto's side of the story. One was a fax from Carola Wutschig, Pallas Group customer service representative, which reads:

"Dear Mr. Böse:

"Herewith we confirm, that we got all of the lacquers for the productions as listed above [matrix numbers listed correspond to those on the LPs.] from Abbey Road Studio, London, in January 1997.

"We already informed you in the past, there is no possibility to do any kind of mastering at Pallas, nor had there ever been such a possibility.

"We hope, to have been of assistance to you.

"With best regard

"[signed] Carola Wutschig"

In addition, I received another, unrelated reissue mastered by Nick Webb at Abbey Road. Fortunately, Webb had handwritten the matrix numbers on the inner grooves of the Argenta LPs (along with the letters "NW''), and on this unrelated issue as well. It doesn't take an FBI handwriting expert to see that the same person inscribed both.

Is that the end of the story? Well, conspiracy theorists might say Pallas is engaged in a coverup on behalf of Alto Analogue, but that seems farfetched to me. So, unless those spreading these "copies of master tapes/digital processing" allegations can put up some credible evidence (send it my way, c/o Stereophile), they should shut up. Until and unless they do, case closed for Mikey.

As for the audible "digital processing" claimed by some, I don't hear it. If that makes me a bad listener, so be it. As one well-known turntable manufacturer said to me when I told him this story, "If that box is digital, I'll take digital every time!"

Mega-dittos.

Hang 'em high!

I had to pass this one on: In a story about the upsurge in table-top radio sales entitled "Big Sound, Little Boxes" in the "Home" section of the March 19, 1998 New York Times, Phil Patton writes: "For years, improvements in audio acoustics have produced such tiny differences that few mortal ears can appreciate them. The huge speakers and towers of components have therefore become hard to justify to the spouse."

Phil's ignorance can almost be excused. (I say "almost" to encourage you to take the time to write him and straighten the dude out before he does serious damage! New York Times, 229 W. 43rd Street, New York, NY 10036.) But what excuse does Richard Watson, senior product designer for JBL, have for saying, in the same piece, "High-quality audio is no longer a destination''? Speak for your own products, Dick.

According to Patton, "Bose has sold about a million and a half of its $350 Waves [radios]." I've heard from some marketing people that last year Bose spent more money advertising that one product than the combined advertising dollars spent by the entire high-end audio industry. Oy Vay!

Some good news, already

Good news for you SOTA owners, past, present, and future. Kirk and Donna Bodinet of the SOTA Sales and Service Center announced March 8 that they are now producing the entire SOTA line, including the Comet,™ the Moonbeam,™ and the top-of-the-line Millennia™ (which I had here for review before it looked like SOTA was headed south). The company also manufactures two record clamps and a vacuum-operated LP-cleaning machine.

SOTA S&SC has been handling SOTA parts, repairs, and upgrades since 1997. Before that, the Bodinets were "primary subcontractors," providing subassemblies and "design guidance" for the above-mentioned products. Original SOTA designer and principal Dave Fletcher consults for the company, and designs electronics for SOTA products. SOTA products, parts, accessories, and upgrades are available both factory-direct and from SOTA dealers.

SOTA S&SC offers a tune-up service for all SOTA turntables. The cost is $150 for nonvacuum 'tables and $175 for vacuum models, including a new belt—itself a $25 item. SOTA will check and retune the suspension, check the motor and drive-unit, the vacuum system, and all other components—including the 'table's cosmetics. Cost for a new box, if you don't have your original, is an additional $65. According to Donna Bodinet, there are around 75,000 SOTA 'tables in the field around the world. This has been a recording.

Speaking of SOTA, how's this for a testimonial? My friend Gary's SOTA Star Sapphire/Shure SME V ended up under two feet of water four years ago when the basement of the house he'd just bought—part of an Amagansett, Long Island inn he has since restored and rents out—was flooded in a freak storm.

The silt-encrusted SOTA sat on a shelf until I cleaned it up last weekend. I took the entire 'table apart and wiped down every surface with Formula 409, or Endust for electronic components. (Great stuff, by the way—and try the $49.98 one-ounce size Signature version, formulated for high-end audio products.) Luckily, the power supply and vacuum pump had escaped the deluge. Once I had it back together again, I replaced the cartridge, fired it up...and it worked perfectly. The 'table spun quietly at the correct speed, and the arm behaved flawlessly. Amazing. Don't try that with a CD player. Cosmetically, it looked as good as new—which means that, in the right light, you can see where the dealer (who shall remain anonymous) used a blue Magic Marker to cover a big, ugly scratch on the plinth when he sold my friend the 'table "new."

Other turntable news: Immedia announced their new, lower-priced RPM 1, which sells for $2495. The 'table, finished in piano-black, features a composite high-mass platter, isolated motor, the same sapphire disc-and-ball bearing system used in the $5995 RPM 2, and a dedicated clamp. Unlike the RPM 2, the 1 features changeable armboards. Speed change is via a stepped pulley, or the user can upgrade mechanically and sonically to the RPM 2's electronic drive system. For a limited time, Immedia is offering the RPM 1 packaged with the RPM 2 tonearm (which I reviewed in the May 1997 Stereophile) for $4495. As the arm alone sells for $2495, this is a $500 saving. This has been another recording.

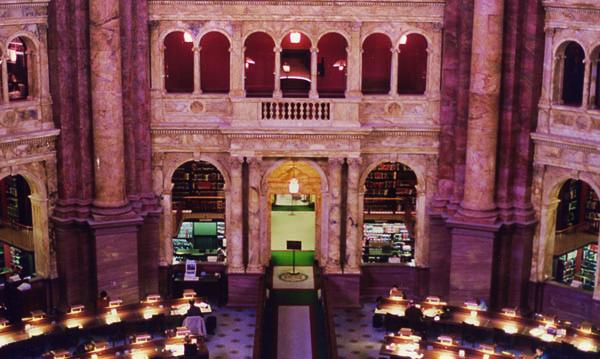

Mr. Mikey goes to Washington

Back in February, Simon Yorke, whose Series 7 turntable I was in the process of reviewing (see review elsewhere in this issue), flew in to Washington, DC, to install two more of his transcription turntables in the Magnetic Recording Laboratory of the Library of Congress' Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division—a perfect opportunity for a one-on-one with the British-based designer. The lure of 3,000,000 mostly unplayed records stored in the Library's archives cinched the deal, and off I went.

Always looking to support outmoded and outdated technologies, I took Amtrak—which, of course, had engine trouble and left almost an hour late. Still, it was far more pleasant than a plane flight, and, by the time you factor in getting to and from the airport, not really that much longer. Plus, when you exit Union Station and the Capitol dome is staring you in the face, you know you're there, not stranded in some godforsaken beltway airline terminal.

You know how some things are just meant to be? Well, get this: When I arrived at the sprawling facility, I was informed by Samuel Brylawski, head of the Recorded Sound Division, that Thomas Edison had received his patent on the phonograph 120 years to the day of my visit! How cool is that?

During my daylong visit I got an insider's look at many aspects of the Library's operations and archives, starting with the facility where Yorke's transcription 'tables have been installed. As I report in my review of the Simon Yorke Designs Series 7, Mark Levinson had won the bid to outfit the room, so it's stocked with Cello electronics, the giant Cello loudspeaker towers, and the Yorke 'tables, a consumer version of which Levinson sells to his customers who still play records. The room is way too small for the system; there are plans to move the facility, and indeed the entire recorded-sound archive, to a separate building outside of DC—perhaps to the former Federal Reserve building in Culpepper, Virginia.

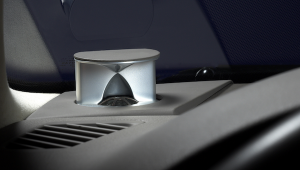

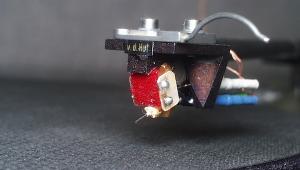

For now, the Recorded Sound Division is conveniently located down the hall from the current record, tape, CD, and 8-track—yes, 8-track!—archives. Yorke's 'tables, which feature and 12" tonearms and 20" platters to accommodate any size transcription disc, sit on Vibraplane isolation tables. The turntables are fitted with special motors and electronic speed controls that allow the user to dial in any speed between 0 and 99.9rpm, and in either direction.

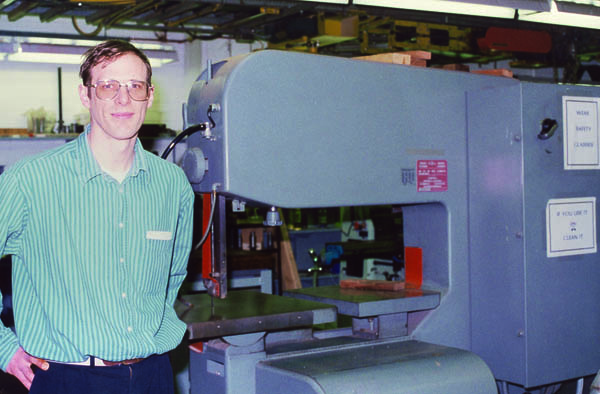

The room is extremely well equipped: I saw Nagra analog and digital recorders, Schoeps mikes, Apogee converters, and other gear usually found only in the best recording studios. Across the hall was a well-equipped video playback facility. Among the experts with whom I spoke was Allan D. McConnell, Jr., whose official title is "Head, Magnetic Recording Laboratory." McConnell told me that, for the time being, 1/4" analog tape was the preferred "preservation format." Digital is too new and as yet unproven. Archivists and preservationists are very conservative.

I asked Mr. McConnell, who oversaw the procurement of the equipment at the laboratory, at what point he'd realized that there was better analog playback gear than the Technics direct-drive turntables they'd been using to transfer acetates and 78s to analog tape. He told me he'd come to the facility five years ago, and after attending AES conventions and other events, had come to realize that the Library's gear was in serious need of upgrading.

Now that he's got the Yorke 'tables installed, can he hear the difference? He told me that while he can't hear the improvement on every disc because some are so bad, for the most part he can, and he's satisfied that the Library is "doing the best job [it] can" to preserve and archive the material it stores. Still, for the time being, the policy is to save the original.

I also spoke with Gerald D. Gibson, whose title is Audio and Moving-Image Preservation Specialist, Preservation Research and Testing Office. We spoke not only about preservation techniques, but also about what's on hand that's worth preserving—which includes all the acetates from Toscanini's NBC radio broadcasts. While NBC donated the acetates to the Library for safekeeping, the network retains the copyright; for the time being, there are no plans to reissue what are apparently surprisingly fine-sounding recordings of many important performances.

The Library is also rich in unissued Duke Ellington material; I was told that Ellington's son, Mercer, spent a great deal of time researching his father's recordings, which include radio broadcasts from the Newport Jazz Festival—none of which has ever been issued due to copyright restrictions.

As the day progressed, I had that hungry, gnawing, empty sensation as I realized I'd yet to see, or been invited to see, all of those mint LPs. I had to ask myself if I really wanted to. It's like strip clubs—what good is putting all that stuff in front of you if you can't have any of it?

As Gibson delved deeper into issues of acquisition and preservation, I popped the question: "Could I see...the records?"

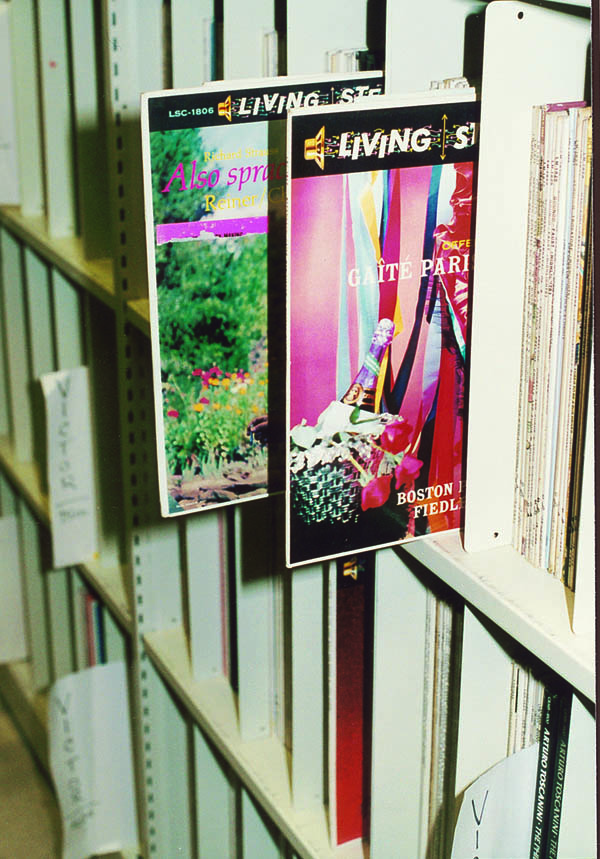

Why, yes, I could. Then the floodgate of questions opened. What would I find there? One each of every record ever made? If I wanted to find, say, a mint, unplayed "shaded dog" of RCA LSC-1806—Reiner and the CSO's famous stereo recording of Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra—would I be able to simply waltz in and pick it off a shelf? Could I hear it? Could I—not as a journalist, but as a member of the general public and a taxpayer—walk in and demand to hear it?

If so, how would I hear it? On what kind of gear? Did I have to make a reservation? Is there a computerized list of every record, CD, 8-track, acetate, and transcription disc in the Library's 3,000,000-piece holding? Could I exchange my noisy copy of LSC-1806 for their mint one and no one would ever know the difference??? Inquiring minds wanted to know!

As Gibson took me on that long walk to analog paradise, he filled in the details: the Library has the world's largest collection of sound recordings. The Copyright Office of the United States is a branch of the Library of Congress, but the federal copyright wasn't expanded to include sound recordings until 1972—hard to believe it took that long.

That means that, from the late 1920s (when the Library began collecting sound recordings) through the early 1970s, submissions to the archives were purely voluntary. So if I did find LSC-1806 on the shelf, it would be because RCA had wanted to submit it, not because it was obliged to do so.

Over the past two decades the Library has received an average of 150,000 new recordings each year. While it should have one of every recording released, if record and/or publishing companies followed the copyright laws to the letter, the fact is that the Library depends on the conscientiousness of those involved—and not everyone is. Due to logistical and budgetary restraints, the catalog is not computerized, nor is it complete. A significant portion of the collection is simply housed on shelves by label and issue number.

Most of the 78s are still in their original packing material, Gibson told me, because they were simply placed on shelves and never opened. The storage facility is temperature- and humidity-controlled, and the collection is divided by size and format. There are approximately 600,000 acetates and lacquers alone.

As either a citizen or a journalist, if I (or you) want to hear LSC-1806, it can be played for me, but I can't handle the recording. It would be played via a remote system set up between the storage facility and wood-paneled listening rooms in another part of the building. But you can't march in off the street and ask to hear something just because you want to. You have to be researching something, though I was told that "research" is loosely defined.

In other words, don't go to the Library and say, "I was passing by and it was really hot outside so I thought I'd come in and listen to some Fritz and the CSO." Instead, say something like "I'm doing research on early stereo recordings, and I'd like to know if you have an RCA recording from 1954, catalog number LSC-1806." You'll have a better shot at hearing it. If they have it on commercial LP, it can be accessed for you in about 10 minutes. Acetates are held in a facility 25 miles away; allow two days.

Inside the archives

I walked through a nondescript door and it hits me: this is a record collection bigger than any I've ever seen or imagined. Row upon row, aisle upon aisle, analog orgasm upon analog orgasm. On the way I pass some issues of Stereophile on a shelf, a dozen or so Technics turntables—nice ones—used to pipe requested music into the listening rooms, and a bank of well-used VPI and Nitty Gritty cleaning machines. Looks like home, but on a scale much, much more grand.

I meet the individual in charge of the nuts'n'bolts, day-to-day operation of the collection, but I'm too flushed to write down or remember his name. He's seen what's on my face before, and he's bemused.

"Okay. Where would I find RCA LSC-1806, if you have it?" I ask.

"Follow me," he says.

We walk, and walk, and walk, past what look like at least a billion records. "Down that row."

I go down that row. I see the familiar RCA spines, and I pull out not one, but two copies, complete with the sticker. I take the records out of the jackets and it's like stepping back in time to 1960. I wouldn't be surprised if no one's touched these records since they were placed on the shelf all those years ago.

More on my visit to the Library of Congress next time.

Footnote 1: A preview head reads the signal a fraction of a second before it reaches the cutter head, giving the lathe time to compensate for heavily modulated grooves by increasing the pitch—the space between grooves.