Analog Corner #7

(Originally published in Stereophile, January 12th, 1996)

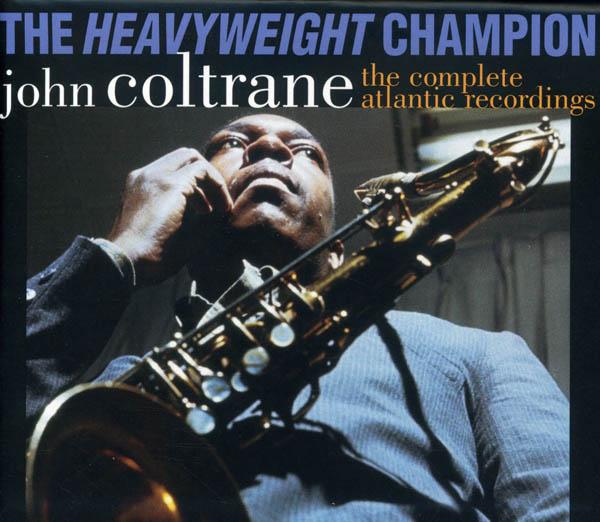

A few days ago I spoke with Gene Paul, the veteran mastering engineer who digitally transferred Atlantic Records' Coltrane catalog for Rhino's The Heavyweight Champion—The Complete Atlantic Recordings (Rhino R2 71984)—a superbly packaged "sessionography" on eight CDs (Footnote 1).

The set sounds outstanding for CD (I haven't heard the vinyl yet), and I wanted to know what converter Paul had used. I don't want to rain on anyone's digital parade, but he told me a stock Sony PCM-1630. No Wadia, no Apogee, no DCS, no gazillion-times oversamping, no SBM box—a stock '1630. "Why?" I asked. "Don't you hear differences among converters?" He said that he did, adding that if you want to change the sound, those devices do, but in his opinion the biggest difference is in the analog playback deck. Once you digitize the signal, he said, "the damage is done." The Coltrane masters were played back on a vintage MCI open-reel deck.

Okay, I give! Analog and vinyl reproduction do not have "infinite resolution," as I claimed here recently, but I didn't mean to be taken quite as literally as some letter-writers took me. Film doesn't have "infinite resolution" either, but compared to current commercial video tape, it does.

Would anyone suggest videotape as an archival storage medium for motion pictures? No. Imagine what would happen to the studio exec who began archiving and "restoring" film on tape, and calling the results superior or equal to the original? They'd be pulling him from the La Brea tar pits.

Analog, both tape and direct-to-disc, has been the benchmark medium for music recording since Edison invented it. Believing the heavy hype heaved with the introduction of 44.1kHz, 16-bit–word digital, the recording industry went on a disastrous frenzy of "archiving and restoring" 80 years' worth of recorded sound using that technology.

You can throw mathematical "proof" of 44.1kHz, 16-bit digital's "transparency" at me until I choke on the numbers; the proof is in the listening, and the listening tells me—and growing numbers within the recording industry—that analog, while not "infinite" in its resolution, does out-resolve the current digital standard, and is thus diminished profoundly in the conversion.

As with film, if the original has higher resolution than the proposed "archiving" medium, the copy cannot be considered archival. A 16-bit, 44.1kHz digital recording stored on CD? Now that's archival. It's also rarely very musically involving.

The current vinyl revival proves three things: one, that a stubborn minority believes that the recorded medium, like film, is part of the message; two, that analog can be an incredibly robust storage medium (listen to those 40-year-old RCA tapes on new vinyl or CD); and three, that analog has higher resolution than 44.1kHz, 16-bit digital. You just gotta listen for yourself.

By releasing the Coltrane material in both formats and in different configurations, Rhino offers music lovers the best of both worlds: a CD set assembled in order of recording dates—a natural for digital—and the original LP master tapes, maintaining analog integrity. Bravo Rhino!

You got me floating

Being a music reviewer, I probably listen to more CDs each week than all of the Stereophile readers who write in and accuse me of being an "analog snob" combined. One of the biggest problems I have with CD sound is its "cardboard-cutout" sonic picture, instead of the sense of three-dimensional images floating in space within the soundstage—an illusion even a budget turntable provides with ease. A few weeks ago I put Audio Alchemy's DTI!SPro 32—a black box which contains resolution enhancement and digital-jitter filter circuitry—between the EAD T-7000 transport and DSP-9000 Mk.3 processor.

For the first time in my listening experience, digitally sourced images actually floated on a cushion of air, creating a sonic picture much closer to analog, and thus much closer to re-creating what I hear experiencing live music. With the DSP-9000's remote, I can switch between AT&T glass fiber-optics and coax cable through the 'Pro 32: the differences are not subtle.

If true 20-bit, 88- or 96kHz-sampled digital via DVD proves to be even better (hopefully much better), I think we'll have digital everyone can enjoy. But for now, DTI!SPro 32 notwithstanding, the all-analog LP version of the same music still sounds much more "real" in my system (ie, PJ Harvey's To Bring You My Love on British import vinyl). However, the Audio Alchemy box could help bring even the staunchest analog diehard around.

You think I'm a diehard? There are still audiophiles who refuse to listen to CDs, period.

Bladder control

Yesterday I placed a Townshend Audio 3 EHD Seismic Sink beneath my VPI TNT Mk.3 turntable (actually under the giant Bright Star Audio "Big Foot" sandbox). The TNT already sits on a massive VPI-built stand, the tubular support pillars of which are filled with sand and lead shot; the whole affair rests on a concrete floor.

So how much better could the sound get? Much, I'm amazed to tell you. It brought the TNT even closer to the sound of the active, pneumatically suspended Rockport Capella turntable I reviewed a few years ago in The Abso!ute Sound.

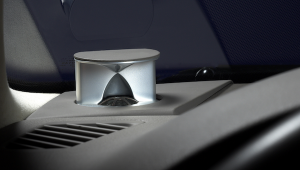

The Seismic Sink vibration-control devices use inflatable air bladders sandwiched between a level-adjustable base and an upper platform upon which you rest the component you've chosen to isolate. The special 27" by 21" TNT version ($725) requires three air bladders, each of which has its own LED that blinks when it needs inflation. A few shots from the supplied bicycle pump and you're back to spec.

What happens to the sound? Focus improves dramatically, the noise floor lowers, images solidify, and the sound takes on a softness which is at first alarming. As your ears get used to the removal of a layer of grain and edge, you realize what you're hearing is much closer to what live music sounds like. The focus is authoritative, but it doesn't come as a result of phony "sharpness." A $349, single-bladder version did amazing things for both the Rotel RP-900 turntable and the EAD T-7000 CD transport.

I did not like the sound that resulted when the smaller Sink was sandwiched between the tube-powered Audible Illusions Modulus 3A preamp and a Bright Star Audio Big Rock sandbox. The overall picture became kind of "gray" and out of focus, and stayed that way even after mass-loading with a Bright Star Little Rock placed on top of the Audible and supported by three inverted cones.

I was talking about Seismic Sinks with an audio writer for another magazine, and before I could tell him what I'd heard with the Audible setup, he commented that he didn't like the Sink with tubed preamps because it cast a "gray, out-of-focus" sound. As they say in the mainstream press: great minds are deluded alike.

Are the Seismic Sinks the last word in vibration control? I don't know. What I do know is that they work, and the price is reasonable. This is a definite "take it home and try it" product for retailers to offer skeptical audiophiles.

Greed, envy, anger, &

high-end audio

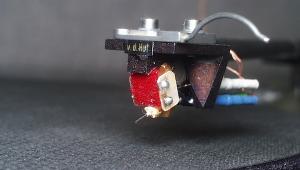

Having just written about a $700 device that goes under a $6500 turntable fitted with a $4500 arm and $2000 cartridge, I got to thinking about the reader who has a $500 turntable and a $129 cartridge. How does this stuff go down with them? Maybe you?

Judging by the letters Stereophile receives from some readers who haven't got the financial resources to afford top-shelf gear, maybe you'd think, "Not well." But I think I'm like most readers: I can enjoy things I can't have. It's an adult adjustment to envy.

Ten years ago my system consisted of a pair of Spica TC-50s, a heavily modified Hafler DH-101 preamp (based on Jung's and Marsh's groundbreaking "Choosing Capacitors" piece in Audio) and DH-200 amp, and my big splurge, an older Oracle Delphi (square motor)/Eminent Techology 1 air-bearing arm combo fitted with an AudioQuest 404i cartridge. Cable was Kimber 8TC. Before the Oracle, I had a Rotel direct-drive turntable (which used a low-vibration, Denon-sourced AC motor) fitted with a Lustre GST-1 arm.

Even with the Oracle, this was not an expensive system, yet it made me very happy because it sounded like music. Fun in those days was trying cheap modifications like packing the bottom of the Rotel platter with Mortite, or globbing a pad of Blue Star typewriter cleaner gum on top of the headshell. Fun was also visiting record stores, which still had records in them.

I remember going to Aron's old store on Melrose in Los Angeles back then. It was almost all vinyl. They kept a few CDs in a glass display under lock and key, which only added to the snobby caché of the new format. I think Aron's had one of those early Denon vertical CD players; even at low volume over the store system, it revealed its digital awfulness.

I used to love watching those entranced by the new medium enter the store with a huff and a stack of records. Making larger-than-life gestures, they'd place the vinyl on the trade-in table as if it was a bag of doody diapers, then reverentially approach the digital temple, accompanied by a store clerk who'd open the Ark and hover around watching for five-finger discounts. (Shit, I'm starting to sound like Edward Tatnall Canby.)

Anyway, every couple of months, a new issue of The Abso!ute Sound would show up. I'd sit there, eyes glazed, reading about all of this new, exotic, and very expensive gear that I could not possibly afford. I could be bitter about my deprivation—I could say to myself, "$700 for a cartridge with a wooden body? What suckers!" Or I could be excited about what I was reading and hope that someday, maybe I could have it too.

Bring a flashlight

I think used-record store lighting is scientifically designed to hide scratches and schmutz. No matter how you flash the records in the store light, no matter what angle you choose—you can squint, put your nose to the grooves, hold them at arm's length—they look pristine. You pay, you step outside, you pop a disc from the bag, and it announces clear as day: "I've been played on a Silvertone a thousand times." You can always tell when the record was owned by a guitarist: the solo in each song is chewed white with groove wear.

There's only one solution: bring a flashlight. Like a zit-faced teenager in fluorescent light, direct light on the grooves really lets you know what's there. Better yet, get a pair of those glasses with the built-in flashlights: you'll look like a dork, but you're an audiophile, so obviously that won't bother you, and you'll have both hands free.

Even if the record looks pristine, wear can be invisible: I always check the hole for wear, and the label for spindle marks. If you see a spider web's worth of spindle marks, or the hole shows white where the colored label has been worn away, the record's been played a great deal; chances are it's worn. On the other hand, you can't always go by looks. It's a good idea to run your fingers over scratches. If you can't feel them, they may not play—especially on mono records, if you have a "mono" switch on your preamp. And if the price is right, why not chance it?

I picked up an original "shaded dog" of Fritz Reiner's Spain (RCA LSC-2230) for 99 cents. It looked trashed; but for 99 cents, why not? At least I could tell if I liked the music. After a thorough cleaning, I played it, and it sounded almost mint, even though it looked like a dry riverbed.

Think i'll dust my broom

You get the dirt-encrusted record home: then what? Vacuum it clean? That's what I used to think, but no longer. I published an article on record-cleaning by Michael Wayne in The Tracking Angle a few months ago that takes the procedure to a fetishist level I hadn't previously considered necessary, or even of value. Now that I've tried it, I'm a believer.

Wayne's position is that vacuum cleaning is the last step, not the first; that vacuum cleaning is what you do only after the record has been cleaned. Indeed, if you have a vacuum machine, you must have noticed (as I have) that many dirty records, even after a thorough cleaning, exude stylus-fouling crud. Sometimes the results aren't that bad, but there's still noise that sounds like dirt.

Wayne's technique involves a series of steps using a variety of fluids and dirt-removing devices that, while complex and time-consuming, really works. The basic principle is that each fluid leaves a residue that must be removed by using another fluid, until the final pass using the vacuum cleaner (Footnote 2).

Using this technique, I've cleaned records I thought were clean but noisy and have ended up with cleaner and much quieter records. They even look different. Unfortunately, one of Wayne's tools is the sadly discontinued Allsop Orbitrac, which is cheap and very effective midway in the procedure.

Analog lovers: we must get the Orbitrac back in production. The only way that's gonna happen is if you pick up the phone and call Allsop toll-free at (800) 426-4303. Ask for Armand Vizina and tell him, "Bring back the Orbitrac!"

One of the first records I tried Wayne's methodology on was an original British pressing of Electric Ladyland (Track 613008/9), bought used by mail. It had little noisy gummy spots on it that wouldn't vacuum off. When I was finished with the pre-scrub, the grain alcohol bath/cotton-pad procedure, the Orbitrac rubdown, and the final vacuum cleaning with Torumat fluid (my choice of final fluid), the gum was gone, and the sound had come in from the storm. Sure, I'd lost a half a day, but what price clean vinyl?

Footnote 1: Rhino's also just issued an LP edition limited to 3000 copies, all analog-mastered and containing the 10 original Atlantic LPs (with original cover art), plus two LPs' worth of previously unreleased material. If you can't find it at your local "record" store, try Rhino Mail order at (800) 432-0020, or True Blue Music (a mail-order service associated with Mosaic Records) at (203) 327-7111.

Footnote 2: If you're curious about Wayne's record-cleaning methodology, a check for five bucks payable to The Tracking Angle and mailed to P.O. Box 6449, San Jose, CA 95150-6449 will get you a reprint of the article. You may not wish to invest the time and trouble to clean every record using Wayne's method, but once you've tried it, you'll know which of your faves need the treatment.