Beatles “End of Days” Produced Chaos and Creativity On the Long and Winding Road to Let It Be (factual corrections per K.Howlett email)

Never mind that the songs sometimes ended up being more individual than group efforts and that squabbling and disagreement led to acrimony as well as long time engineer Geoff Emerick exiting, producer George Martin going on holiday and even Ringo Starr walking out for a few weeks.

The resulting 30 song album, which took five months of work, released November 22nd 1968—the 5th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination— proved to be among the group’s most popular and it remains so.

A little more than two months later, workaholic Paul McCartney called the others back to the studio to work on the next Beatles album, one that all four Beatles decided should “get back” to the group’s original ethos of a band playing live—something it had not done in front of an audience since The Beatles played a 30 minute set in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park August, 29th 1966 before 25,000 screaming fans and let’s not forget 7000 empty seats.

The group decided to write and record a new set of tunes and document the rehearsals and recording sessions for a half hour TV documentary after which the group would perform live three times for invited fans, including plans for a proposed live TV concert. What could possibly go wrong with the “Get Back” project?

As it turned out, just about everything, caused in great part by a total change of production methodology, venue and difficult to resolve conflicts among and between the four now creatively territorial adults.

They chose to write all new material that would be filmed for a documentary, rehearse on an enormous soundstage and then record in a newly built studio using engineer Glyn Johns.

On January 30th, 1969 not long after rehearsals had begun The Beatles played an unannounced concert on the rooftop of the Apple Corp headquarters that was recorded for the documentary, performing nine takes of five songs, three of which would later be included on the Let It Be album, but meanwhile the group was also working on material that would result in the Abbey Road album.

The group released in April of 1969 the single “Get Back”. While the Apple sessions were still underway, Glyn Johns gave the group some acetates of mixes or early takes he'd made that the group rejected. The release of his later May 1969 compilation of a proposed Get Back album kept getting delayed because of the delayed release of the edited film footage. Even by March 1970, according to Kevin Howlett, "... it seemed that Glyn's compilation with some alterations – 'Teddy Boy' omitted and 'I Me Mine and 'Across The Universe' added – was going to be released. Phil Spector was brought in at the end of March 1970 and that's when Glyn's compilation was rejected – although not by Paul, who didn't know what Spector was doing". Meanwhile back in May the foursome went to work on Abbey Road, released September, 1969.

Most of this activity took place “under the radar” especially in America, so that in the fall of 1969 when Abbey Road was released most fans other than the hardcore followers figured that was the group’s intended next release after The Beatles.

Abbey Road proved to be among the group’s most popular and acclaimed records and remains so. By then the group had, for all intents and purposes broken up.

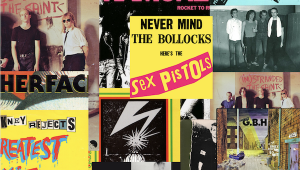

As the cataclysmic decade came to a close, rumors of a Beatles break-up surfaced and soon thereafter “the dream is over” became a reality. The group that had become a linch pin in the lives of a generation was no longer. The decade that seemed to climax with Woodstock and then Abbey Road ended with a depressing thud when it became clear that the “Fab Four” were no more.

Meanwhile, work continued to complete the Let It Be album, which included studio recordings produced at Apple headquarters, engineered by Glyn Johns interspersed with live rooftop songs. While the goal was an album of recorded live tracks with no overdubs, that didn’t happen and what did happen is a long, complicated story sorted out with great efficiency in the outstanding annotation included in both of the recently released digital and vinyl disc Let It Be sets.

By the time the final Beatles album was released in May of 1970 the young generation that had grown up with The Beatles, knew that the group had broken up and the Let It Be album, a mashup of studio and “on the roof” live recordings that had been Phil Spectorized with overdubbed strings and choir on three tracks ("The Long and Winding Road", "Across the Universe" and "I Me Mine", omitting “Don’t Let Me Down”, which had been the “B” side of the “Get Back” single (George Martin wrote and produced the much simpler arrangement added to the song "Let It Be") seemed like an “cash grab” afterthought (though that term had yet to be invented). The unappealing cover art, with each Beatle in his own box, especially after the whimsical Abbey Road cover didn’t help. According to Howlett, the Glyn Johns Get Back was slated for release until Spector was brought onto the project.

Though it was ready for release earlier, Let It Be wasn’t until May of 1970 because it conflicted with the release of McCartney’s eponymous solo debut. For his part, McCartney was so upset with what Spector had done to “The Long and Winding Road” that he sent a sort of cease and desist letter to Allen Klein warning him to never again do such a thing and years later to organize the 2003 Let It Be Naked remix that stripped away all that Spector had added. Whew!

The Let It Be Deluxe Vinyl and CD Box Sets

(There also is a "special" 2CD 26 track edition and a "standard" 1 CD and single LP vinyl edition, but I think AnalogPlanet readers will either want nothing or everything).

Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who, having produced, directed and edited a series of successful Beatles promotional films and videos, was hired to direct and produce the “Let It Be” movie (his name was lampooned in “Spinal Tap” becoming Sir Denis Eton-Hogg president of Polymer Records). His final cut documented an acrimonious, unpleasant environment that didn’t exactly add luster to the project.

If the producers, archivists, mixers and annotators of this project had a mission, it was to prove beyond any doubt that while The Beatles’ “End of Days” was turbulent, chaotic and occasionally acrimonious, the foursome were still fab following the 1968 release of The Beatles and their time together creating Abbey Road and Let It Be was both incredibly productive and especially filled with great music-making and camaraderie.

Their job was made all the more easier because of both the film footage (that director Peter Jackson has assembled for a new documentary soon to debut on the Disney Plus streaming service) and the fact that the film crew’s two Nagra mono production tape recorder was constantly running throughout the Apple sessions, rehearsals and jams.

Annotator Kevin Howlett was tasked with going through many hours of tapes and then assembling a coherent running order to which was added a selection of songs and musical experimentation recorded multitrack by Glyn Johns and mixed recently by Giles Martin for this compilation. The results can be heard on the double LP Get Back Apple Sessions, Rehearsals and Apple Jams, which document an exciting collaboration as the guys work through material for both Abbey Road and what became Let It Be.

Those discs and the book alone are worth the price of admission, but also included (finally) is an authorized version of bootlegged and very raw Get Back album that does include a version of “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Teddy Boy”, the latter included on McCartney’s eponymous solo debut album. Why Johns put “Let It Be” back to back with “The Long and Winding Road”, which in my opinion makes little compilation sense, is not explained in the annotation, not that it really matters.

Also included is a 45rpm 4 song EP containing a previously unreleased Glyn Johns 1970 mix of “Across the Universe” and a similar one of “I Me Mine”, a new mix of the original “Don’t Let Me Down” single and one of the original single version of “Let It Be”. That’s the vinyl package.

The digital version includes the same book in a slightly smaller format (and with a non-laminated cover) and a fold open insert containing 5 CDs and a Blu-ray disc of the same material including the 4 above mentioned songs on one CD. Yes, it’s a waste of "valuable" polycarbonate, but it’s the only way to correctly present the contents. The Blu-ray includes a Dolby Atmos 48kHz/24 bit DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix, and a 96/24 PCM stereo mix, though as with previous Beatles packages you can’t download the 96/24 PCM stereo mix from the disc to your computer to have on your stereo system’s music server, which to me is inexplicable, but whatever.

Overall I think this is among the most successful stereo mixes of the entire series, in part because there was less (if any) “moving around” and/or “fixing” to do. The recording was originally to 8 tracks and there was minimal overdubbing, which was the original intent. As with the previous mixes, the timbral balance is midrange-rich, bottom end strong and top end “reticent” compared to original pressings (I like more “snap” to snares and “sizzle” to cymbals as can be found on the original U.K. pressing) but the minor “in the pocket” balance updates produce insightful and enjoyable improvements on just about every tune.

There’s also a bit more compression than I like so when you put all of that together on the opener “Two of Us” Ringo’s 1/8th note snare hits that lead into the bridge “You and I have memories….” lacks the expected “snap” and the way he sneaks up the intensity of each of the 8 hits, which I’ve always found fascinating are both missing in action (this was confirmed by a well known musician friend of mine).

Miles Showell’s ½ speed mastering works really well on this set and unless you really don’t like this album, you’ll surely appreciate the mixes and mastering on the “mature” tunes: “Across the Universe”, “Let It Be” and “The Long and Winding Road”. Nothing can make “Dig It” palatable but it’s short and it’s a “period piece”.

Finally, the copy I got was sealed and not “special” though it was in that every 180 record in the set was perfectly pressed: flat, well-centered and quiet.

The YouTube video I made embedded below had a few comments that said, “You can’t polish a turd”. This record may not be the jewel in the Beatles catalog but a turd it’s not! If it’s a piece of anything, it would be a piece of history every Beatle fan would enjoy learning about by reading the book and listening to the Apple Sessions, Jams and Rehearsal records in preparation for Peter Jackson’s movie. If this is the end of the Beatles reissue remix road, it’s a fitting place to stop, though as I say in the video, I’d sure like to hear AAA reissues of the catalog done like the mono box set. Wouldn’t you?

We can't put "music" and "sound" dials into features stories but I'd give this remix a 7 for music and an 8 sound.