Esquivel Rising!

I Love the Music of Esquivel: So Zu Me!

Esquivel: Other Voices, Other Sounds/Four Corners of the World

Bar/None AHAON-090

Esquivel: Exploring New Sounds in Stereo/Strings Aflame

Bar/None AHAON-091

Esquivel: Infinity in Sound, Volume 1/Infinity in Sound, Volume 2

Bar/None AHAON-003

(1 and 2) Produced by Johnny Camacho, (3) produced by Neely Plumb

Reissue Supervision: Paul Williams for House of Hits Productions, Ltd. Digital transfers by Mike Hartrey

Digitally remastered by dbs Digital, Hoboken, NJ

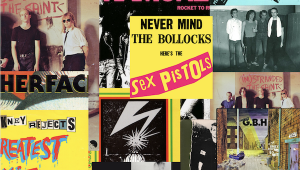

This whole Cocktail Nation, Space Age Bachelor Pad Music revival thing strikes me with extreme bemusement. All of a sudden, a new generation discovers and decides that what was once unhip is now the coolest—whether martinis, leopard skin, kitschy Fifties furniture—or the "easy listening" instrumental music popular at the dawn of the Stereo Age.

Well, I don't want to cop a cooler-than-thou attitude—these days, I'm so out of step with current pop culture trends I might as well be living in Kamchatka—but hey, I've been listening to—and digging—quintessential Bachelor Pad artists like Martin Denny, Les Baxter, Edmundo Ros and their peers for decades. Sure, as a record collector, I initially got turned onto them for the wrong reasons—most of these artists recorded for Golden Age labels in Golden Age sound, and in my early record collecting years, I'd give any RCA Living Stereo, Capitol Full Dimensional Sound or London FFSS a listen, regardless of musical content, just to revel in the sheer sumptuousness of the sound.

But, as I listened to the colorful orchestrations and inventive arrangements of these pioneers of ping pong, I grew to love their styles—none more so than one Juan Garcia Esquivel, or Esquivel as he's universally referred to. To me, pianist/arranger Esquivel is the absolute untouchable king of instrumental music, with an inventive flair for arranging and sense of musical playfulness unmatched by anyone else. To hear Esquivel is to be immersed in a musical parallel universe at once evocative of a time gone by, and a time that, in truth, never was—however wistfully we may long for the simpler, unblemished pleasures of a bygone era, it never really existed that way except in music such as this.

Thanks to these wonderful re-issues from the folks at Bar None records, you can now hear what those of us who have been scouring the original RCA Living Stereo LPs at garage sales, thrift shops and out-of-the-way used record store bins have known all along—Esquivel was an outrageous musical genius, the likes of which the world hasn't seen before or since.

Esquivel would take standards and well-known classical themes and arrange them using a cornucopia of strings, brass, electric guitars, organs and vocal choruses, along with god-knows-what else—Theremins, jaw's harp, marimbas and mysterious instruments rarely seen or heard seen North of the Border (Esquivel originally came to the United States by way of Mexico City). All overlaid with a fantastic assortment of every type of percussion instrument conceivable-bongos, guiros, maracas, castanets, trap drums, timpani, and on and on.

The arrangements are a heady mix of Latin rhythms, lush strings, staccato brass stabs, hockey-rink organ, and a kitchen sink of wild and crazy sounds juxtaposed against it all, sometimes appropriately, sometimes bizarrely. "Begin the Beguine," Lizst's "Hungarian Rhapsody," "Tico Tico," "Harlem Nocturne," "Lullaby of Birdland," "My Blue Heaven," "I Love Paris" and dozens more—all grist for Esquivel's idiosyncratic musical mill.

His musical sensibility meshed perfectly with the "show me the stereo!" recording sensibility of the dawn of the two-channel era, where the producers wanted to exploit the stereo effect to its most exaggerated and excessive—instruments and vocals jump at you from left, right and center, deliberately arranged and placed in the mix to be startling in their sonic impact—the steel guitar "bar crashes" alone will leave you palpitating—all against a background of sweet strings and seductive, soothing background vocals. The earlier albums are more restrained and "normal"-sounding; by the time of the Infinity albums, Esquivel was unstoppably, arrangementally outrageous.

As if all that weren't enough, Esquivel can truly, assuredly be mistaken for no other arranger thanks to his towering musical trademark, his indelible contribution to musical history: the use of the nonsense syllable "zu." In song after song, his vocal choruses sing the syllable "zu" to carry the melody, often to inappropriate excess. I've been told Esquivel did this to get away from everyone else's cliched use of "la, la la" or "doo doo doo"—he succeeded! Trust me, you haven't lived until you've heard Esquivel's arrangement of "Malaguena," with the melody taken by a mixed chorus singing, "Zu zu zu, zu zu zu, zu zu zu zu, zu zu zu!" For this alone, Esquivel deserves legendary status.

And the sound! Originally recorded in legendary RCA Temples of Tone Webster Hall in NYC and RCA Victor's Music Center of the World in Hollywood, California, the sound on the original LPs is hallmark RCA Living Stereo at its best, all the way—big, lush, wideband with excellent bass definition, with that trademark open, present RCA Living Stereo midrange, pure, extended RCA Living Stereo highs and airy, voluptuous RCA Living Stereo hall ambience. Transient response and dynamic impact? You and me should be so responsive and dynamic! Of course, there's a great deal of "ping pong" stereo, where instruments are panned hard left or right-or even panned from left to right and back again (as in the piano in "Jalousie" from Infinity Vol. 2)—as it should be in this music according to the rightful laws of G-d and Man. The sound, even though recorded over the course of several years and at more than one recording venue, is surprisingly consistent RCA "house" sound-a bit more lush in the case of Strings Aflame and more astringent on the Infinity recordings.

The sound of the re-issues is remarkably close to the originals. The re-issue producers researched the RCA archives and selected the best available source tapes, which were then transferred to DAT in what I'm told were straight, flat transfers. These DAT tapes were then used to produce the CD re-issues, with no compression. Noise reduction was used only in spots where it would not compromise the sound—indeed, the original tape hiss is audible in places, though unobtrusive. Note that in a couple of spots, there are flaws in the tape that I swear sound like a mild record popping noise!

Overall, the CD reissues have greater dynamic range and are actually a hair more transparent than the LPs, I think, while the LPs are a bit sweeter and more euphonic-sounding. (I had all the original LPs except Four Corners of the Worldon hand for comparison.) The exception being Infinity in Sound Vol. 2, where the CD is somewhat flatter-sounding than the LP, without as much instrumental presence and dimensionality. And the channels on Other Worlds, Other Sounds are reversed.

About that interview with Esquivel we promised—well, I tried, he said sheepishly. I called the number Bar/None gave me, and a young-sounding woman answered the phone with a cheerful "Bueno!" After I explained that I was calling from The Tracking Angleto speak to Esquivel—and didn't speak Spanish—she instructed me, in perfect English, to call another phone number and assured me I'd reach Esquivel there. I did so, and a woman answered the phone in Spanish—who did not speak English. I was too embarrassed to utter the few words of Spanish I know—"no habla Espanol!" and asked in slow, halting English: "I'd like to speak to Esquivel." I could hear her put down the phone, the sounds of many adults and children talking loudly in the background. After a few minutes an old man came on the phone, who I could absolutely not understand. "Esquivel?" I asked? He muttered something unintelligible.

Then the woman who answered the phone originally came on again. "Esquivel! Esquivel! I need to speak to Esquivel!" I said in growing desperation; another few minutes elapsed, and the same old man came on again—hard-to-hear and again utterly unintelligible. I finally, resignedly said good-bye—without a word of acknowledgment from the old man—and hung up.

I don't know whether I was actually speaking to Esquivel or got a wrong number—but I was too embarrassed to call again and try once more! Maybe I did get to say hello to Esquivel after all—I certainly didn't get a chance to tell him how much I've loved his music over the years.

But at least you now have a second chance to hear Esquivel's magnificent music in all its multifaceted, mirthful splendor, thanks to Bar/None. They don't write, produce, arrange, record or engineer 'em like this anymore. Maybe the Fifties and early Sixties were a better time, after all.