Immedia RPM-2 tonearm Page 3

The look, the feel, the sound

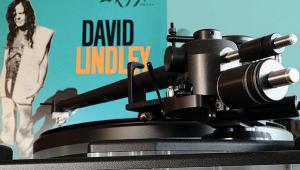

With everything set up and ready to go, the Immedia RPM-2, with its matte black and stainless-steel accents, cut a low-key, businesslike appearance on the VPI turntable—more like an impressive piece of machinery that's had its outer shell removed than a piece of sculpted audio jewelry. Despite my complex description of it, the RPM-2's outward appearance is simplicity itself, a tribute to its well-thought-out design.

The combined armlock/cueing mechanism feels secure and sturdy, and the unique, laterally operated, nondamped system gives you total control at your chosen speed in both directions: You're never left waiting for the stylus to reach the record. Because the cueing mechanism must transfer lateral movement to vertical, the arm shifts sideways almost imperceptibly each time you raise or lower the cueing lever. I didn't have a problem with this—especially as I found the curved fingerlift user-friendly, and the arm's overall stability such that I did most of my cueing by hand. This is one unipivot that feels like a conventional arm—it doesn't flop over when you lift it.

Having heard the RPM-2 at HI-FI '96 on Immedia's turntable with a Clavis DC feeding a CAT preamp, CAT amps, and Audio Physic Caldera loudspeakers, I had a certain expectation of what it would sound like, and I was neither disappointed nor surprised.

First of all, the RPM-2 had the deepest, most dynamic, most controlled, "fastest" bass response I've ever heard in an arm. While the JMW Memorial arm that I reviewed last January (Vol.20 No.1, p.171) had equally good extension, it could not match the RPM-2s bottom-end focus, stop-and-start control, dynamic slam, speed, and tonal purity. The RPM-2 didn't just give me "bass," it gave me the instrument creating it—its timbre and texture—with absolute authority. The RPM-2 surpassed the Graham's bottom-octave performance by a considerable margin, and absolutely creamed my reference, the Rockport 6000.

I pulled out all my bass-rich LPs: The Small Faces' Ogden's Nut Gone Flake (British Immediate IMSP 012); Davy Spillane's Atlantic Bridge (Cooking Vinyl 009); Elvis singing "Are You Lonesome Tonight" from Elvis's Golden Records Volume III (RCA LSP-2765), in which the bass player drags his stand-up across the studio floor during the chorus (don't ask why); The Power and The Glory (M&K Realtime RT-114); The Rolling Stones' Sticky Fingers (Mobile Fidelity MFSL-1-060)—and subtler fare: Classic's superb new reissue of Earl Wild, Arthur Fiedler, and the Boston Pops performing Gershwin's Concerto in F, Cuban Overture, and "I Got Rhythm" Variations (LSC-2586); and Alto's wowie-zowie reissue of Espa;tna (SXL 2020), and an original I picked up at a garage sale for a buck (nyuk, nyuk).

The RPM-2 delivered the bass goods better than any arm I've ever heard—always under control, always making music, never surrendering to one-note monotony or bloat. Of course, if you don't have a subwoofer or a full-range system that goes down to 20Hz and below, you won't hear any of this. But if you crave the wave, you've got to hear this arm.

More impressive, though, was the way the arm "hung together," bottom to top. To my ears, the RPM-2 was, essentially, tonally neutral, while maintaining an unsurpassed ability to deliver transient speed and incredible dynamic energy throughout the audio band—a "fast"-sounding arm. When a drummer hit the snare hard, the arm "popped" the energy level and the music sounded supercharged. Small dynamic gestures were carved out of spaces that other arms simply fly right over. Its speed, its ability to deliver the rhythm and pacing of real music, killed me every time.

As I expected from its low crosstalk performance, the RPM-2 provided a gigantic soundstage with superb center focus and equally impressive image solidity at the extreme sides and back. I could follow rear-wall reverberant trails as they ricocheted off hard surfaces and slid out of earshot. On superb studio recordings like John Hiatt's "Lipstick Sunset" (from Bring the Family, Mobile Fidelity MFSL 1-210; a record that belongs in every audiophile's collection for music and sound), the clarity of the reverberant picture behind Hiatt's voice—the way it set up, moved, and disappeared—was truly remarkable. So was the timbre and texture of Ry Cooder's slide guitar.

Here's a heretical statement: The RPM-2's timbral balance was virtually identical to good digital. Okay, okay, calm down. I believe, at this point in time, that when Bernie Grundman masters, say, Mingus's Tijuana Moods for Classic Records (LSP-2533) on both vinyl and gold CD, the results should be timbrally identical when played back on topnotch gear. There is no reason why the high frequencies should sound rolled-off on the record, or the bass should be more bulbous and "warm," or dynamics should be flattened compared to the CD. With the RPM-2 and any of the more neutral cartridges I used with it, in direct A/B comparisons using a remote-control preamp and precise level matching, that's what I got. I defy anyone reading this to distinguish, on the basis of timbre alone, LP from CD.

Of course, when you listen for small musical gestures, air around instruments, three-dimensionality of images, and the communication of emotional content—something you can't measure, so of course it doesn't exist—the record kills the CD. You understand completely why you lose interest in CD sound after a few minutes, while records can keep you thrilled for hours.

In fact, the closer the timbres, the closer the two formats sound, the more devastating the differences reveal themselves to be, and the more evident it becomes that digital sound—at least 16-bit, 44.1kHz digital sound—is an emotionally disturbed, emotionally insipid medium. As Neil Young once said about it, "The mind has been fooled, but the heart is sad."

Sonic downside

For the same reasons some think the Classic reissues don't sound as natural as the original RCA Living Stereos, for the same reasons some prefer the warmth and midrange purity of single-ended tube amps to even the best solid-state designs, and electrostats to dynamic drivers, not everyone will appreciate or admire the RPM-2's sonic performance. No doubt some will find it too "etched" on top, too "lean" in the midbass, not "fleshed out" enough in the midrange. And if your system doesn't plumb the depths, with no midbass gut hanging out to warm things up, the RPM-2 might sound "thin."

- Log in or register to post comments