Should You Sample DJ Format's Devil's Workshop and DJ Shadow's Endtroducing?

Devil’s Workshop

Project Blue Book PBB-LP003

Music 9

Sound 9

Mixed by DJ Format, Matthew Smyth

Lacquer Cut by JSA (Jukka Sarapää)

Mastered by Matt Fletcher

The sampler is an instrument offering virtually unlimited sonic possibilities, and yet, it presents few sonic characteristics of its own. If a sample is well-recorded and minimally processed, no-one might notice that it is a sample. A drum break by, let’s say, Rotary Connection, is played from the turntable, runs through the sampler’s ADC, into the sampler’s memory, undergoes processing, and passes out to the world through the sampler’s DAC. Will that sample sound perfect? Unlikely. The record it was sampled from was possibly found on the floor of a record shop basement. Maybe it wasn’t even that well-recorded to start with, and the pressing was rudimentary, and now it has footprints and cat pee on it. The Shure M44 cartridges and needles on the turntable were not designed for audiophile reproduction, they were selected to stay in a record’s groove even while a hyperactive scratch-pervert is manually assaulting the playing surface of the disc. Technics 1210 turntables suffer regular abuse, and it is possible that all of these machines and discs are exposed to an environment where alcoholic beverages and recreational substances are consumed. Even for a producer with good ears and a technical aptitude with audio production machines, the sample will have ‘character’.

That ‘character’ may manifest as clicks, pops or scratches from the record surface. It may sound compressed, or exhibit uneven frequency response or speed fluctuations. Even with all of these compromises, a sampler offers an artist contact with material which can be manipulated. The intrinsic qualities of the material itself render all of those faults as secondary. Would you like a perfect color print of a lousy photo, or a grainy photocopy of a great photo? Similar choices apply in the universe of sampling. Aesthetic decisions triumph over technical compromises. An artist like DJ Shadow can loop that magical drum break, all fuzzy and clicky, and layer it over a minor-key electric piano phrase by a Finnish keyboard artist, while stuttering that voice yelling “…midnight…”. In fact, the creative technical options bestowed on an artist by sampling technology are almost infinite, and are rarely affected by the limitations of imperfect sound. Once artists are free to limitlessly mangle and layer and decontextualize the sound of anything, a few sonic compromises barely even register. Now that sampling is an established compositional approach, the fizzy clicks gain their own charm through repetition. It was inevitable that artists would eventually use software tools to add to audio recordings artifacts like hiss and distortion to to make them sound like they were sampled.

The French late-20th century artists and provocateurs the Lettrists and Situationists “hijacked” established imagery in order to deface it. The intent of their détournement was to diminish privileged cultural positions, topple them from their pedestals, mock the very canonical basis for cultural importance. The intent in “sampling, “ripping off” or “appropriating” images or sounds is critical to the outcome. The intent of DJ Kool Herc when cutting together breaks from soul and funk records at a block party was celebratory; take the best section of a great record, isolate it and keep playing it repeatedly to string together a sequence long enough to dance to. The intent of the Lettrists was destructive and nihilistic; upend capitalist cultural values to replace them with other more politically acceptable ideologies. The intent of DJ Shadow and DJ Format is neither celebratory nor destructive. It merges B-Boy methods and music production techniques with a librarian’s obsessive questing for knowledge and a film composer’s urge to amplify emotions and sensations. What then is the intent? A sampled work is composed of material, not music. The material may be musical, but lifted from the original context, the music is no longer representative of the composer’s intentions - it has been rendered into raw material, and the intentions of the renderer are undecided, mutable, and possibly non-musical.

In the late 1990’s here in Glasgow, most post-club evenings would end up in some friend’s flat, where it was more or less obligatory to decompress from a long night of hammering techno with a dense soundtrack of downtempo albums by the likes of Portishead, Tricky, Nightmares On Wax, Dr Octagon, or Tosca. DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing….. was also on heavy rotation, and it is in that 4am context that I learned to love the stuttering sampler and melancholy darkness emanating from this now-classic piece of instrumental hip-hop. I could make some glib joke about Endtroducing….. needing no introduction, but I realize that some readers were possibly pre-occupied with Oasis or Nigel Kennedy at this point, and so a brief contextualization of this record will be necessary.

Josh Davis made this ground-breaking hip-hop album not in Compton, not in The Bronx, but in Sacramento. The album was not released by one of the burgeoning US rap labels like Def Jam or Interscope, but by a small independent acid-jazz label from London, England called Mo’ Wax. It should be obvious by now that the music is not typical of hiphop in 1996 either. There are no rappers. There are no blunts, ho’s, or Glock-9s. It does not even require a “Parental Advisory” sticker on the front. Eliot Wilder has written a book in the “33 1/3” series on Endtroducing….. comprising a lengthy interview with Davis, which should be a primary source for anyone interested in the context and process that yielded the album (Endtroducing….. by Eliot Wilder, 2006, Continuum Press, New York).

Billed as the first album to be composed and produced entirely with samples, the process grew from Davis’s teenage obsession with making mixtapes and learning to scratch on turntables. Sending his material to college radio shows, slowly moving from using four-track cassettes to the Akai MPC Sampler, Davis evolved his form firstly by making beats for other artists before producing material that reflected his own sensibilities. Sacramento was hardly B-Boy Central, but Davis used the makeshift studios of friends in Palo Alto and San Francisco to embark on pieces such as “What Does Your Soul Look Like?”. He has referred to this track as “my depression masterpiece”, and this alone indicates that DJ Shadow was taking a distinct path from other contemporary hiphop producers. Introverted yet confident, Davis had no gangster credentials to boast about in his tracks, so chose instead to express dark optimism, slurred and staccato rhythms, glimpses of otherworldly new-age harps smeared into jackhammer beats.

These contradictory collisions and counter-intuitive decisions seem to be emissions from a mind in flux. Lonely melodies give way to flashes of humor, blissful tonal colors are assaulted by percussive interjections. Electric pianos, musical boxes and pipe organs wrestle with chunky funk and soul breaks, which are chopped and stuttered into a rhythmic abstraction of the source. Disembodied voices utter non sequiturs; detached from their original context, these somewhat meaningless utterances emit a curious emotional resonance. A smiling girl explains “I came to America, found Xanadu, and I knew that all I wanted to do was roller-skate.” It is an oddly banal audio fragment that nevertheless conjures hope and innocence amongst the liquid Björk synths and clattering snares of “Mutual Slump”. Equally, the frantic, stuttering “n-n-n-n-n-now it’s approaching MIDNIGHT!” of “Midnight In A Perfect World” is filled with joyful anticipation.

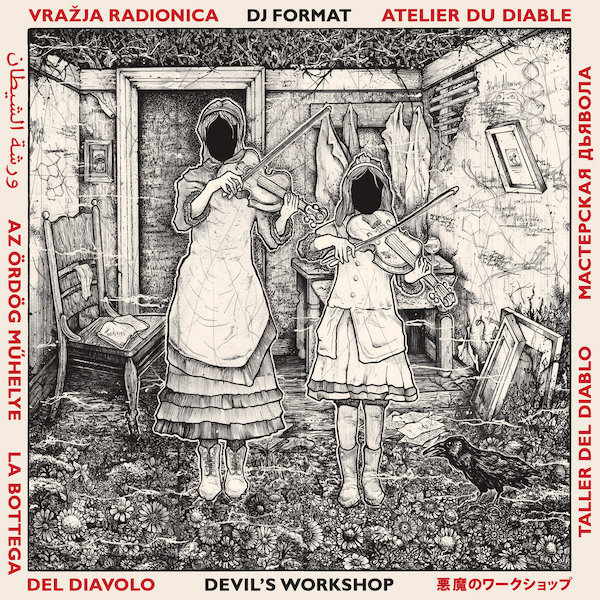

DJ Format may be best known for his 2003 album Music For The Mature B-Boy”(Genuine/PIAS GEN 005 DLP) featuring rappers such as Jurassic 5’s Chali-2NA and Toronto’s Abdominal. To appreciate his DJing prowess, look to his 2006 Fabriclive 27 Mix (Fabric54 CD), a storming feel-good soul party stuffed with wild psychedelia, rolling breaks, and vocal magnificence. It is easily one of my favorite mix CDs from Fabric’s long-running series, and Format somehow seamlessly unites tracks by Cut Chemist and Coldcut with Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone; by the time he is blending Ananda Shankar sitar grooves with English jazz singer Cleo Laine, you are in no doubt about his mixing abilities or the depth and breadth of his musical appreciation. His latest release Devil’s Workshop is a dark, cinematic album that does not immediately call to mind hiphop, and it may be fair to say that the connection stems more from the production methods and cultural approach than any superficial resemblance to Public Enemy or Kanye West. The psychedelic feel of the compositions and the superbly gothic sleeve illustrations by Rough Stuff 77 suggest a complete departure from the norms of US rap and hiphop. This excellent Perlich Post interview with Matt Ford offers an insight into the production of the album.

DJ Format has succeeded in a feat of misdirection in this release, by collating and assembling these samples in such a way that the record sounds like a live studio band. The sensation of a well-rehearsed combo jamming in a sleazy club is an illusion. Every note stems from samples, the curse of every record company administrator and the payday cheque for countless copyright lawyers, the bone of contention for generations of soul, funk and jazz players who overheard their grandchildren playing some hip-hop that impossibly seemed to feature themselves on horns or drums.

Descending the imaginary stairs to The Devil’s Workshop Club in pitch darkness, following the throb of the music, you eventually feel your way through a curtain and now you can hear the band properly. Unfortunately, you can also now see your fellow guests; people of the netherworld, creatures of the night, phantoms of your imagination, pursuers from your nightmares. Smoke, darkness, the scent of decadence, the sense of abandonment. You find a safe corner from which to observe The Devil’s Workshop House Band.

The rhythm section are heavy dudes with heavy lids on heavy ‘ludes. The drummer has been playing this basement every night for thirty years, his sidekick on double bass still considered a newcomer after twenty years. They are soulmates with a telekinetic connection; mind readers of funk, brothers in psychic soul. The guitarist is mainly hair with occasional glimpses of Les Paul. The keyboard player has a whole music shop before him; Rhodes piano, Hammond organ, vibraphones… it seems like he has an extra hand that magically emerges to augment his impressive tonal contribution. But through the haze, smoke and candlelight, is that a harp player? Is there a flautist too? A sinister, uncanny sensation overtakes you, like an English horror movie or a detour into David Lynch’s “Inland Empire”.

That basement full of untrustworthy characters and long-suffering musicians does not exist, except between your ears. This collection of downtempo songs they have composed and played is a mirage. In fragments, the musicians still play that riff, or snap out that break, but many of them died years ago and play no more. DJ Format however, has produced a collection of songs which conjure a living representation of a non-existent band of psychedelic sonic explorers. You can virtually see them on stage, casting sidelong glances at one another, the drummer nodding at the bass player, the guitarist eyeballing the keyboard player in a hopeful attempt to remain in key as the latter extemporizes.

The vibraphone theme in “Time To Listen” conjures a sense of a very mournful Mulatu Astatke paired with a poignant viola and spoken vocals, which are ultimately punctuated by a Hammer Horror scream. The pace picks up and frazzled guitars deepen the unease. After another sixteen bars the pace increases again, like a pursuer gradually closing on their panicking prey. The insistent bass and slow drums increase in menace as the track progresses into tension and uncertainty. The machine gun snares of “The Light” are paired with crime-movie flute lines and sinuous orchestral strings - the theme to a cop film you’ve never seen but which sounds eerily familiar. “Brainstorm” is a psychotropic expression of sensory disquiet and ennui, shaped by tense guitars and a backbeat of sparse soul. Thunderclaps and a hammy tenor express resignation while orchestral strings and woodwinds emit tonal colors. “Warm Dust” opens with a despairing voice but soon picks up with snare scratches and boom-bap before a hopeful guitar line yields to a bumping, funky jam full of cuts and vocal interruptions. Another galloping change of tempo brings the groove in harder; would a producer direct a studio band to push their tempo from 100 to 120 BPM before the end of a song? Probably not. Would a DJ push the pitch slider from 0% to +8% to provoke the crowd? Absolutely.

“Peace” makes a slinky entrance with reversed sitar and a solid, unhurried rhythm before unfolding into a drowsy jam with tablas and guitars; a further progression into clavinets and a more emphatic drum pattern demonstrates the breadth of the compositional approach taken here. As side one closes, it is abundantly clear that this is not simply a few loops brought together in software; this is a deeply complex form of arrangement that is undoubtedly harder to achieve than simply asking the guitarist to lay down another take. If the (sampled) take does not fit, then the search continues to unearth another compatible riff that can fit the arrangement. Both Format and Shadow are “diggers”; if you have ever flipped through the unpromising bins of a second-hand record store, they have been there before you, extracting unwanted curiosities with odd vocals or eerie science fiction sound effects, and rare discs which may not be intrinsically valuable but are priceless because they contain that drum break, that bass groove. The pressing is clean and punchy, and presents the rich, warm, exotic compositions with a softened high frequency that complements the darkness of the material. The sleeve is a heavyweight matt chunk of stiff card stock reminiscent of the 70s.

What DJ Format has achieved in his composition and arrangement on Devil’s Workshop is something of a different perceptual experience to DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing…... Both are entrancing, perplexing productions, composed entirely of samples rather than the expressions of a live band. But was DJ Shadow motivated to emulate a dream band of musicians that he could never assemble in the studio in real life? I don’t believe so. Endtroducing….. is a formal exercise in producing a hyper-real examination of material, a collage approach to composition which allows the plastic nature of sampled audio to yield a new form which is neither definitive of its source, nor representative of its destination as “hiphop”. Devil’s Workshop is more of a cinematic journey rather than an emotional one. Neither of these releases feel much like conventional hiphop, so if you have avoided listening because you thought you knew what to expect, now is the time to reconsider - and if you like what you hear, take a further step with the work of the late J Dilla, or the output of TEEBS on Brainfeeder Records.

Endtroducing…..

Mo’ Wax/Island/UMC ARHSDLP007(Abbey Road Half-Speed Master Edition)

Music 10

Sound 9

Mixed by DJ Shadow

Mastered by Miles Showell, Abbey Road Studios

DJ Shadow was not merely re-visiting the usual James Brown samples in these productions. It may be impossible to identify every sample used in Endtroducing….. but the website whosampled lists a surprising mix of new age incantations, David Axelrod, Meredith Monk, Giorgio Moroder, Metallica, Tangerine Dream, Alan Parsons Project and Björk alongside soul and funk rhythms from Rotary Connection or Billy Cobham. These sources provide texture, atmosphere and emotional dimensions as much as they provide jamming breaks or funky yelps.

The new 25th anniversary half-speed pressing of Endtroducing….. arrives in a gatefold facsimile sleeve with Obi-strip and an Abbey Road certificate of authenticity. The two LPs are contained in high-quality stiff card inner sleeves, printed with an updated set of credits but laid out to look very close to the original. The outer sleeve of the new disc is printed in a cooler shade than my original, but apart from this slight deviation in tone and color, and a light fuzziness, the artwork is a faithful representation.

The important part is in the grooves. To learn more about half-speed mastering, read this excellent piece featuring none other than Analog Planet’s very own Michael Fremer. The article also yields technical insights from Abbey Road’s Miles Showell, who completed this half-speed remaster of Endtroducing…... Half-speed mastering claims to produce more accurate high frequency content with better fidelity, and I can confirm that upper-mid and high frequency material benefit from enhanced clarity in this new pressing. Certain vocal and effect samples have emerged from the muzziness of the original pressing with a crisper and more legible quality. I also have to report that there is a slightly compressed feel to the new pressing, a minor flattening of dynamics. Not only that, but the overall cut is 1-2 dB quieter than the original - I am estimating this from the meters on my mixer, but it is certainly audibly quieter. I can live with these alterations, as they are minor, and there is a definite improvement to higher frequencies which provides sheen to the sound. There is, however, a noticeable attenuation of bass in the new pressing. The original pressing does what hiphop fans want - the bassline bangs and slaps, the low end is dominant and alive, booming and thumping along underneath the kick drum. The new pressing, in spite of a decent low end response, seems to have a slight hollowness in the bass, and is a little more controlled. It is possible that an engineering decision was made to balance the mix in order to enable the best cut. It is also possible that an aesthetic decision was made in re-mastering, to depart from the original mix for some reason to address matters of taste. If someone offered me the option to have improved high frequency reproduction and as much bass presence as the original, then I would say ‘yes please’. It is a little unfortunate that the new pressing does not quite encompass both. The re-issue restores “What Does Your Soul Look Like (Pt 4)” to the position it occupied on the original CD release, which confused me a bit, but is welcome. If you do not own a copy of Endtroducing….. and you can’t find a good original pressing, buy this new pressing of this seminal record.