Audio Legend Harry Pearson Passes Away

Forgive me for making this obit a very personal remembrance. I first encountered Mr. Pearson in print when I read my first copy of TAS in the early 1970s at a friend's New York City apartment. At the time I'd lost all interest in audio. I read Stereo Review, High Fidelity and Audio and like many had been dragged down into the world of measurement "perfection" and so slowly over time I'd replaced a rocking tube-based system with some very poor sounding but well measuring solid state gear of that time. I still loved music of course, but listened with less passion than I had in the late '60s as the sound receded into the background. The loss of interest was so gradual, at the time I didn't take notice, nor did I realize how far down my system's sound had sunk.

Walking into my friend's home I was confronted by what looked like large white room dividers. They were Magnapan Tympani 1C speakers. The rest of the system as I recall it consisted of a Kenwood KD-500 turntable, Sonus cartridge, Infinity Black Widow tonearm and Audio Research SP3A preamplifier and D120 amplifier.

I had never heard of any of these brands. They were not even mentioned in those other magazines. I felt cheated. I felt I'd been had. Taken for a ride. This was a new and very expensive world but when for the very first time I sat down to listen my world literally changed forever.

This was a system recommended by Harry Pearson in his magazine (arguably among the first "Zines") The Absolute Sound, which my friend plopped into my lap. Pearson was a former environmental reporter for Long Island's Newsday newspaper. The magazine was quarterly, Reader's Digest sized and print heavy. At the time it did not accept advertising. The cover art by ROBBII was dark, dense and the antithesis of what magazine covers were/are supposed to look like but they were works of art, visual puns and instant classics. I didn't read it because I was too overwhelmed by what I heard. I'd never before heard anything like it: so expansive so "real" sounding and so musically believable.

I ordered a subscription and immediately fell under the spell of Pearson's eloquent writing and the almost mythical goings on at his Victorian home in Sea Cliff, L.I., N.Y. There were the listening rooms that he would describe in misty detail. There were the writers he had assembled and the manufacturers he venerated in print, many of whom also went on to become legendary. I'd read about Pearson's famous annual "friendship parties" where the young industry's luminaries would gather to celebrate their success and pay tribute to "HP" who almost single-handedly (along with Stereophile's founder J. Gordon Holt) re-invented a moribund business that had become mass market, mundane and culturally irrelevant.

It may be difficult for some today to understand how one person with almost zero technical skills or understanding (Harry never did set up his own turntable) could so transform and/or invent a business segment but there's little doubt that he did just that using the power of the written word, a sophisticated esthetic and a world-view and descriptive language that he can rightly claim to have almost single-handedly invented.

Pearson and crew (and J. Gordon Holt too who first inspired Pearson) reviewed audio equipment based on how it sounded not on how it measured on the test bench. At the time that was revolutionary. Yes, the language could be dense and jargon-filled but Pearson probably modeled his invention after the then fairly obscure and lofty world of wine criticism, which today has easily surpassed audio in terms of dense and silly descriptors: wine can taste of leather, of asphalt, with hints of B.O. but it must never taste like a grape!

Of course these small, upstart audio companies like Audio Research, Magnepan, Mark Levinson along with some of the "old school" brands like McIntosh and Marantz were founded and existed without Pearson and in some cases well before he began writing about "high end audio" but by the time he got involved, the culture of "hi-fi" so popular and cool in the "Mad Men" 1950s and early '60's and venerated in Playboy as the epitome of hip (and the best way at the time to remove a girl's dress) had faded out almost completely.

Pearson more than anyone was responsible for inventing a new market segment—a home—for both the older, then fading companies and the new ones and for putting them on the radar screens of the well-off who could afford to buy the very pricey gear. Pearson turned hi-fi from tech to a cultural phenomenon by making it always about music and about the people.

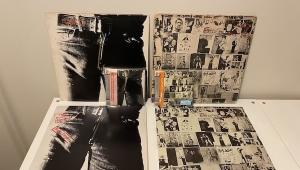

Pearson along with TAS writer Sid Marks and a few other LP experts attracted to the magazine venerated the RCA "Living Stereo" and Mercury "Living Presence" records. Like The Foo Fighter's Dave Grohl does today on his HBO TV series "Sonic Highways", Pearson elevated the status of certain recording studios and venues like Kingsway Hall as well as legendary recording engineers like Kenneth Wilkinson, Robert Fine and Lewis Layton and producers like Jack Pfeiffer and Wilma Cozart Fine.

As Wilma Cozart-Fine's son Tom related to me in an email upon learning of HP's passing: "I can tell you for a fact that Harry's articles and commentaries about Mercury Living Presence were read by and had influence on decision makers at Polygram, and the same was true at RCA/BMG. At Polygram, the methods employed to make the Mercury CDs, and their success in the marketplace, were widely adopted throughout the company. Competitors at Sony and BMG started digging in the vaults to find real-deal master tapes and started caring about analog playback, simple signal chains and state of the art analog-to-digital conversion, raising the bar on quality for all classical CDs. I'm not saying it was just Harry, but Harry's voice was important."

Back then when a friend would call and ask what was going on I'd say "a new issue of TAS just arrived". "I'll call back tomorrow" came the knowing response. All else had to wait. Even though back then I couldn't afford any of the gear reviewed in TAS, I read it from cover to cover immersing myself in the colorful descriptions and the excitement of the reviewer describing hearing familiar music as never before.

Pearson and TAS put into focus for this listener an unclear past. He put the puzzle pieces together. Of course I grew up listening to Belafonte at Carnegie Hall and recognized its sonic greatness but I never knew why, and even as a young boy found exciting the "RCA Living Stereo" logo but reading TAS put into focus all of these experiences. I'd lost touch with that era as rock took over but rediscovered it in TAS.

I was always a big Roy Orbison fan but I didn't own any of his Monument label albums. I saw in a store The Very Best of Roy Orbison and bought a copy in "stereo" figuring it would be electronically reprocessed junk. When I played it, the sound was astonishing. I later read in TAS about engineer Bill Porter and another piece was fit in the puzzle.

Yes, HP could be very frustrating. Sometimes Harry would start a review and end it in mid-review with a "more next issue" ending and that "more" would never come, or a promised review would never appear in print or after anointing a product as "the best" (which would cause the faithful to run out and buy it) an issue or two later he'd reconsider and rescind his recommendation by pointing out a certain "fatal flaw". It was all part of the game and most readers loved playing it. But not all. Pearson would publish the nastiest "letters to the editor" and then, incredibly, produce an even nastier response! He was having none of that "the customer is always nice" stuff. Sometimes, as I recall it, he'd cancel a subscription and refund the reader's money.

In 1980s I was doing some writing for the Los Angeles music publication Music Connection edited by my friend Bud Scoppa. I'd followed the introduction of digital recording first heard on vinyl and even though I'd been primed by Stereo Review and the other mainstream magazines to love the wider dynamic range, the absence of tape hiss and scrape flutter, I found the sound of Ry Cooder's Bop 'til You Drop literally disorienting and nauseating. From day one TAS was on the case covering the promise and the hugely disappointing sonics. I heard the same things and began agitating in Music Connection. At the same time, recorded sound regardless of technology was taking a huge hit probably in great part because of a rampant recording studio cocaine epidemic. Sound got hard, brittle, wiry and edgy like a good coke high.

I wrote for Music Connection a piece called "We'll Get it Wrong in the Mix" and when it was completed I realized what I'd written would not have been possible without my TAS readership. I was in many ways parroting what I'd read in TAS but what I'd read in TAS was a reflection of what I'd come to experience.

Around the same time that story was published the latest issue of TAS included a note from Harry Pearson looking for a new pop music editor. I Xeroxed a copy of that piece and mailed it off to Sea Cliff.

That proved to be another life-changer for me. I got a call from someone on the TAS staff. HP loved my piece (how could he not? It mirrored everything I'd absorbed from a decade's worth of reading TAS!) and would I come to Sea Cliff and meet with him.

"Yes!" I said, of course, and in the Spring or early summer of 1986 I made my pilgrimage to Sea Cliff, heart pounding as I ascended the wooden porch steps. You have no idea what that felt like after more than a decade of reading about and imagining the Sea Cliff saga comings and goings. Now I'd meet the legendary HP, the image of whom, at the time, it must be remembered, never appeared in print! I had no idea what he looked like. Today that kind of tight control seems inconceivable but back then it was possible. Once he allowed ROBBII to paint a full length HP portrait but only from behind. It was almost shocking.

I'd previously met many famous people. Back when I was on the radio one night I talked up the then fairly obscure Peter Frampton (then with his band Camel) and he was in Boston and happened to hear me. He came up to the studio. I'd met Paul Rodgers, Ray Davies, and later while working on "Animalympics" and "TRON", Gilda Radner, Billy Crystal, Harry Shearer, Graham Gouldman, Jeff Bridges, Wendy Carlos, etc.—not that most would ever remember meeting me—and you realize that "people are people", though there are many special ones whose charisma is unmistakable.

But I have to say, having by then met and worked with some famous people, when HP's door opened I was more flustered than ever before. I'd read this guy's writing and I literally worshipped his magazine, but I had no idea what he looked like or really, who he was beyond the mythical in-print character he'd so carefully crafted.

I shook hands with Harry Pearson and was immediately struck by two visceral emotions: on the one hand he had a gruff, undeniably charismatic and commanding presence and a deep, from the bottom of the diaphragm voice that was authoritative and in some ways intimidating, but on the other I felt from him an incredible sadness. I felt as if he was thinking that somehow, meeting him would be a disappointment for me. I could almost hear him thinking to himself "Okay, now he's met me and he's disappointed so let's move on to business." I felt that he felt he was like "The Great Oz" and I was Dorothy peering behind the curtain. An apt analogy as it turns out.

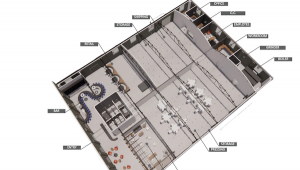

Since I was expecting Harry Pearson to be a human being and not a mythical character, other than that odd sensation of feeling his feeling my disappointment with him, I was not at all disappointed—though I was taken aback by the size of the mythical listening room in which he had the giant Infinity IRS loudspeakers and Goldmund Reference turntable. The room was barely large enough to contain the speakers! You sat but a few feet from these enormous monoliths. How could this sound any good? But as soon as he put on a record I heard good that was way gooder than anything I'd ever before heard and those four giant columns completely disappeared leaving a holographic three dimensional picture the likes of which I'd never before heard.

Ironically I now have a similar circumstance: giant Wilson XLFs shoehorned into an impossibly small space but I get similar results here as every skeptic who's visited will attest.

Harry Pearson could be a most charming, warm and giving person as he was to me that afternoon. He had only wonderful things to say about the piece I'd submitted. He autographed the then current TAS "To Michael with great respect, HP" and he offered me the pop music editorship, which came with a yearly "stipend" that could hardly be called a "salary" but no matter, I had other income sources and it was a dream come true (okay maybe I didn't dream large enough) to imagine soon seeing my name among the staff list that then included John Nork, Robert E. Greene, Jack English, David Wilson (that David Wilson), John W. Cooledge as well as record reviewing celebrities (in my world then) including Ed Mendelson, the aforementioned Sid Marks, Robert J. Reina, Fred Kaplan, Frank Doris, Arthur B. LIntgen, Enid Lumley and Martin Colloms. These were important names to me. I hung on their every word and in some cases still do.

I moved back east from California (something I'd been planning to do anyway) and began my pop music editorship at The Absolute Sound. I was in!

Harry first assigned me to interview the legendary recording engineer Bill Porter. For that I flew to Nashville and boy was it fun meeting Bill and hearing his stories about Elvis, Roy and the others he'd recorded.

The pop music editorship was enjoyable, I got to interview some musicians and a few industry people. At the time I owned a PS Audio preamplifier and was assigned to interview PS Audio's Paul McGowan. The interview appeared in the Nov/December 1986 issue. But I wanted to be an equipment reviewer. I told this to HP and he sent over a pair of budget Seifert Research speakers to compare to my Spica TC-50s.

I had no idea what I was doing but I wrote the review. It was returned with HP's red pencil all over the place. He'd clearly spent a great deal of time with it and I was grateful. I re-wrote it again and again, each time getting it back with suggestions for improving the grammar the content and the structure. Until one version returned with no red mark-ups. I was finally ready to review audio equipment for The Absolute Sound.

When I heard this morning of HP's passing, what first came to mind was the time and effort he put in to help me become a better writer—one good enough to appear on the pages of the magazine I thought mythical even when I got close enough to see it from the inside, big, ugly metaphorical zits and all. It was that good back then and I learned so much from it and from Harry Pearson that I will forever be grateful. Wherever it is I am now, I don't think I'd be here if it was not for Harry Pearson. In fact, I'm not sure where this industry would be today, if anywhere, without Harry Pearson—and that is not death-borne hyperbole.

There are so many memories flashing by now: the time I told VPI's Harry Weisfeld at an audio show in 1988 that I was about to get married and he responded "Thank God!". I said "That's an unusual response." He said "Well, everyone in the industry assumed you'd moved east to work for TAS because you were Harry's boyfriend." I survived the fall to the floor.

I got married in October of 1988 but had to postpone my honeymoon because Harry Pearson was throwing a 15th anniversary party in Sea Cliff that week and I was scheduled to give Bill Porter a "Lifetime Achievement Award". Harry had to keep the guest list "tight" so incredibly, even though she had to endure a honeymoon delay my new bride was not invited to the gala nor were some other women. Well, my wife was having none of that. She called Harry and scorched his phone's receiver. She got her invitation and as I recall it (could be wrong), she made sure that the other uninvited women also got theirs. We ended up with a Pearson Maine Coon cat, after which and for all time he affectionately called my wife "pussy mama". Only Harry could get away with that one.

Harry was from the South and from a time when being closeted was a necessity but he was cautiously open among his friends. At one point before gay marriage was even a dream in the minds of that community Harry held an informal, not recognized by the state of New York wedding with his then partner and many in the industry, even those made uncomfortable by it, attended to show their support. I donned a blond wig and sang "The Look of Love" as Dusty Springfield. I figured given what people thought anyway, I had nothing to lose.

Another great memory of that time was attending a famous Harry Pearson friendship party. The first one I attended was yet another fantasy come true. Every year in the fall, on or around Labor Day Weekend, Harry would throw this enormous party to celebrate his friends and his friendships and the wonderful camaraderie the industry created. Upon approaching the house you could hear and see in the distance the crowd filling and spilling onto the walkway beyond the generously sized wrap-around porch. A Canadian flag fluttered against the golden late summer sky high atop his Victorian home's turret. It was audio Camelot. The closer you got to the porch the more familiar the faces.

Everyone who was anyone in the audio industry and beyond was there. They flew in from around the world to pay homage to Harry Pearson, without whom it could easily be argued, many of them would not be in this wonderful business. I was an unknown at the time so spent most of the party eating the outstanding catered food (Harry was a gourmet), drinking the heavily alcoholic blender drinks and gawking at the audio celebrities wherever you looked. What a time!

Here's the sad part of the story that really needs to be included in any honest remembrance: not that many years later, the party had moved on. The friendship party attracted but a few friends—literally a handful. I remember being there with Frank Doris, a few other loyal Harry supporters and staff and that was all. The porch was empty. The industry had lost patience with some of Harry's less attractive, some would say abusive behavior that eventually led to his tragic downfall.

He had a large garage full of unreviewed equipment that was never returned. Or equipment would be returned having been seriously damaged by his cats. I was at the house more than once when Harry couldn't be bothered coming down from the home's upper level to greet manufacturers who sometimes traveled from overseas to bring and set up equipment for review.

I remember going upstairs and pleading with him to just come downstairs and say "hello" but for reasons known only to him he wouldn't, though in the evening he'd be happy to be taken out by that same manufacturer for an expensive meal where he'd order embarrassingly expensive wine regardless of the manufacturer's ability to afford it.

The once flush magazine's finances became dire over time as revenue dried up and Harry continued to feel entitled to live large and lavish while those in his employ were late getting paid. Had he run the magazine more like a business and less like a personal fiefdom perhaps he too could have "cashed out" like Stereophile's Larry Archibald did at the height of the magazine buying boom. Unfortunately, despite efforts by loyalists to tighten the magazine's lax business practices, conditions got worse. Despite fierce loyalty to the brand that once got me barred from a CES Stereophile party and a stern (and deserved) dressing down from Larry Archibald, I quit The Absolute Sound.

It was surreal. I'd devoted myself to the magazine and to Harry Pearson's vision, in which I firmly believed and I was left with no choice but to leave and hope something else would come along. Some people think Harry Pearson and I were "enemies" but nothing could be further from the truth. He believed in me and gave me my start in this business and he taught me how to write an equipment review. How many young writers today are given such careful mentoring? Judging by much of the slop found in print and especially online—the fawning publicity pieces posing as objective, critical reviews—I'd say a few, but not that many.

So a great man died last night. Some of you younger readers who have encountered online some of his later writing may have trouble understanding his greatness but if you go back and read his earlier writing which was fearless and brilliant, you'll understand.

Harry Pearson deserved better in his later years. The pieces of his magazine were picked up by others who kept the name and little else. He wrote for the new TAS but his heart was never really in it and he didn't feel respected, valued or particularly well-treated. He was eventually "fired", though he still had a large, loyal following particularly in Asia where I'm sure news of his death will shake many.

For some time friends had been encouraging him to start an online by subscription only website that would generate a decent income for him. I know for a fact there were offers to build the site for him gratis but he declined. I don't think he was interested in doing the hard work required by a website presence, especially one funded by paid subscribers.

Eventually he did start a site called 'HP Soundings" but what he did write was a shallow shell of what he was once capable of producing. He was going through the motions. Much of what was presented on the site was written by Joey Weiss who was as loyal as anyone ever was to Harry Pearson and I'm sure HP valued Joey's loyalty and friendship.

At least, through the assistance of friends he found a way to remain in his beloved Sea Cliff Victorian, where he was found last night. To be brutally honest, I think it is fair to say that just as Harry Pearson in his younger days was singularly responsible for creating his own greatness, he was also singularly responsible for his tragic downfall. He was not a victim of circumstance.

While for an obit ending that may sound harsh, I think Harry Pearson would be the first to agree and approve. Beyond the mythical man he cultivated in print the man I knew was above all else a realist. Our first encounter told me so.

Harry Pearson could be charming one moment and irascible the next. He had a temper and he did not suffer fools easily. He was a wonderful dinner companion and boy did he have stories (though I can't count on 10 hands how many times he stood up my wife and I after making dinner plans—in that we were not alone). Many great writers in other fields befriended him. His passion for audio was contagious. You might enjoy this high performance audio magazine story written in 1990 by the great film critic David Denby who upon meeting him, fell under Harry's spell.

I didn't see him all that much over the past few years but I will miss him. We all will. Even those of you who never knew or heard of him.