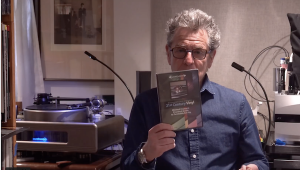

Bassist and Recording Engineer Steve Albini

I conducted this interview with the great Steve Albini way back in 1993, before MP3, before the iPod, back when all but a few outspoken critics like Albini, Neil Young and a few others had anything negative to say about the digital recording revolution. It's fascinating to read Albini's thoughts today. He was right on target then, as he is today.

-Michael Fremer

He's the dean of alternative rock engineers, a thirty-something (now 43) veteran of literally thousands of get 'em in, get 'em out recording sessions, mostly with young, inexperienced bands who can't spend a great deal of money, but who have something to say and who don't want to be restrained in the recording studio. More than anything, they want to recognize themselves when they hear the final product.

With Albini at the console, the results are raw, ballsy, honestly recorded representations of ensembles playing (mostly) live, in acoustic spaces. In other words, audiophile quality sound, but applied to music many audiophiles probably won't care for. That's their loss.

Albini's productions are big on space and image focus and are engineered to highlight the sense of ensemble- of musicians communicating with each other as they play. While Albini's recordings are brash, and sometimes bright, they explode with excitement and musical truth. His recordings have fired the imagination of a generation of musicians who want to be heard on record the way they play live- a method of recording pop music that all but disappeared with the advent of multitrack tape recorders in the mid to late sixties. Albini has also opened the ears of the listening public to the sound of honest recordings. And for that audiophiles of every musical bent should be grateful.

What prompted this interview was the first play through of Albini's 1992 recording of P.J. Harvey's Rid Of Me (Island ILPS 8002 514 696-1 LP). Albini outdoes himself here, aided no doubt in part by a reasonably large major label recording budget. "I've got to talk to this guy", was my first reaction beyond Harvey's extraordinary performance.

With the help of Lori Somes, P.J.'s publicist, I contacted Albini at his home studio in Chicago. Yes, he would be happy to speak with me. I procured passes for Albini and a friend to the summer C.E.S., and hooked up with the two at The Chicago Hilton.

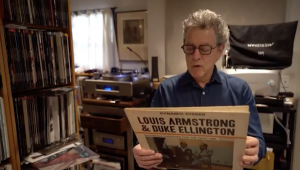

Long, thin, and thoughtful looking, with a close cropped head fitted with wire rim glasses, Albini had "bass player" written all over him, and indeed that is his instrument. We spent a few enjoyable hours traipsing through the exhibits listening to the vinyl and CDs he'd brought along-some he'd recorded, some done by others-before ducking into an abandoned utility closet- the only place we could find that would be quiet enough to conduct an interview.

We spoke in a small dark almost air-less space strewn with stacks of broken chairs, empty glass cleaner bottles, assorted rubble, and discarded industrial grade upright vacuum cleaners. A perfect setting, I thought

MF: I got a letter from a reader who said I should "check out the recordings of the great Steve Albini" and at that point I had only one record with your name on it- Surfer Rosa by The Pixies on Rough Trade records, which I hadn't yet played. So I did, and it blew me away because it was in every sense of the word, what an audiophile recording should be.

SA: Well thanks, I'm flattered.

MF: What I mean by that, is it captured a space- and musicians playing in it and I don't care if they play amplified or un-amplified instruments. So my question is who is this person, and where did this audiophile sensibility come from?

SA: I'm sure it's the same notion that drives all people who want to hear music reproduced accurately. I'm a fan of live music and when I listen to a recording I think it should in some way be representative of the band that's playing. I talk in terms of rock bands and other engineers may talk in terms of quartets- its essentially the same thing. Its a performing unit that is the heart and soul of any style- whether its a solo performer, a vocalist, a symphony orchestra, or a rock band- that performing unit is what the entire genre is based on- what the entire notion of that music comes from. So my skills have all been developed, to the exclusion of virtually all of my other skills, most noticeably personal hygiene and dress- to try and make accurate recordings of rock bands. Pretty much my whole reason for getting up in the morning is to make a better, more flattering, more accurate recording of a rock band than I did the previous day.

MF: Why are there are so few engineers who have that perspective. I mean, forget about actually being able to do it, so few aspire to that.

SA: Most recording engineers aren't fans of recorded music, first and foremost. They are fans of engineering first and foremost. And so they like to do things as engineers that reveal to other engineers things about their knowledge, or their hipness within the engineering community. That's overstating it somewhat, but I think to a greater degree than most engineers admit, they don't really listen to music. They don't go see live bands very much, they don't listen to records much at home. Some producers carry with them the notion that they are part of a continuum of producers each of whom has a distinct style and personality that must be imposed on whatever band or artist they are recording. I don't come from that perspective at all. When I'm making a record with a band, the band is in charge. I am there as a technician, essentially, to make what they do every day as part of their normal life, to make that come across the speakers to someone listening at home.

MF: I've always said that the majority of pop engineers today think of artists as voltage sources for their processors.

SA: Exactly! That's a really good way to put it. Politically they can be a nuisance as well because the artist may very well want things to be one way or another and if the producer is not of that frame of mind and he can get the record company to agree with him, then the only sticking point is the damn artist gets in the way wanting to play an F#minor- that sort of thing.

MF: So how did this esthetic develop in you? Where did you grow up- just a quick overview.

SA: My very early childhood I traveled across the country because my dad moved from California to Washington D.C.. From about nine years of age I lived in Montana. All of my formative years, my adolescence was there. All of my tastes developed there, pretty much in isolation from the mainstream popular culture because this was before there was MTV, USA Today, CNN and things like that that made information leap across the country to every small village. Montana was still relatively isolated culturally.

MF: Was there music in your house?

SA: My folks were big fans of the Folkways recording series, so my earliest memories are listening to records like Hedy West and Hoyt Axton and Ledbelly and folk and blues recordings that were made more as documentaries than as esthetic undertakings. My dad was also a huge fan of Johnny Cash and other country and western hillbillies. We had a monaural hi-fi that he had built himself. Had a really nice Heath vacuum tube amp and Heath turntable which he built. Had the crudest idler wheel drive of any turntable I've ever seen in my life. The speed control on it was approximate at best.

MF: Was it a tapered shaft?

SA: Exactly. And you could move the idler up and down the shaft. The arm weight about a pound and a half and you'd turn it on and let it heat up for a while and it would sound fine. All of my early music experiences- even when I became a teenager and was listening to punk rock records, I was listening on this old vacuum tube monaural Heath hi-fi and I developed a very crude sense of what recorded music really sounded like. And it wasn't really until I got to college in 1980 that I was able to see live rock music to any extent. I'd seen a few stadium concerts, but I'd never seen a three piece rock band in a club environment until I came to Chicago.

MF: What made you want to become an engineer? Had you met musicians that wanted to be recorded, and you did it?

SA: That was a big part of it. A lot of it is just the tinkering urge that everybody gets. When I was in Montana I was in a punk rock band and we wanted to make recordings of ourselves...

MF: What did you play?

SA: Bass. And the only way to make recordings of yourself was to find somebody with a tape recorder and borrow it and some microphones and experiment. I spent the better part of a summer just tinkering with a tape recorder and finding out what different things did. I didn't really learn anything, but I got all the tinkering out of my system early on. So now I don't feel the need to punish other musicians with tinkering.

MF: But you came from the perspective of a musician so it was a position of respect for what music is, as opposed to what the technology is.

SA: I've been in bands as a musician, and I've been a fan of music for longer than I've been recording bands on a professional level.

MF: At what point did it become apparent to you that other bands were going to ask you to do their recording?

SA: It just started happening. I was in a band called Big Black that was reasonably successful on an independent level, and other bands admired the way our records sounded and we had done the bulk of our own recording, and so people started approaching me about recording their bands, because at the time, in the early eighties, most recording engineers were unsympathetic to anyone who played actual rock music. Engineers in that era were all trained to do voice-over and jingle recording sessions. Or “lite rock” and pop without any esthetic imposed on it. It was just a matter of getting the music on tape and putting the voice on top.

MF: Except the heavy producers at the time.

SA: Right, and the heavy producers' stuff of that era, there was no level of aggression in that music, except for a very few hard rock recordings of that era, the emphasis was always on a slick classy quality and never on balls or impact. And the bands that I was dealing with-the bands that I was a fan of- all operated on much more gut level, on a much more immediate esthetic. It had nothing to do with being smooth or well crafted. All that mattered was taking the audience by the collar and shaking it. So what an ordinary engineer would consider a good recording would be one where the VU level was appropriate to the tape and where the noise floor was acceptably low and the instrument isolation level was good enough. For me the criteria would be one that surprised me and made me ears perk up and one that accurately reflected what the band was trying to do.

MF: Did the first Sex Pistols record do that for you?

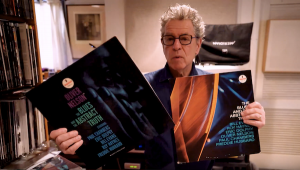

SA: Yea! That's a great recording. There are many great recordings that are not generally recognized as great recordings by people when they discuss techniques and things like that. There are some recordings that I think are timeless and perfect. Alot of people talk about Beatles records in that regard. I think they're flattering to the band and I think they're pretty good, but there are many other recordings I think are as good if not better. The first Television album I think is an absolutely astounding recording. Its the first time in my life where I ever thought "wow, that's a nice high hat!" There's a record that was done a couple of years ago by a group called Slint, from Louisville, Kentucky, the album's called Spiderland and that I think is one of the most amazing records I've ever heard.

MF: What label is that on?

SA: It's on the Touch and Go label. I brought a copy of it.

MF: Cool, we'll play it.

SA: It was executed by a friend of mine, Brian Paulson, who's done many good sounding records, but this one is one of the most strikingly stark recordings of a rock band I've ever heard. Its totally, completely unaffected and bald, and as a result you can hear every detail of what everybody is doing and it happens to be an amazing band too.

MF: They have to be to get away with that kind of recording. A lot of what's being done now is covering for the fact that musicians can't play.

SA: And there are expectations that audiences have for a level of production on certain recordings. If a Van Halen album came out sounding like this Slint album,

Van Halen fans probably wouldn't appreciate it. People like me might find some use for Van Halen at long last, but that's not likely to happen. If you go to see a rock band at a club there will be three people playing instruments and somebody singing. When you go home and listen to their record there may be as many as six or eight parallel guitar tracks doing the same thing, merely to provide a cushion of sound under a multitrack vocalist that's undergoing a whole lot of dynamic processing generally massive compression, heavy duty EQ and a lot of digital effects, and that will be supported by a rhythm section that's heavily compressed, electronically recorded bass guitar with drums that are likely as not gated, at best, or at worst, sampled off of other recordings and you end up with something that bears some resemblance to what went in, but it can't in any sense claim to be a representation of the band.

End of Part I