Movie Music Recording King: Shawn Murphy Part I

(This Interview originally appeared in Volume 1, issues 5/6 of The Tracking Angle, published in the winter of 1995/96)

Ever hear an LP copy of Maurice Jarré's soundtrack to "Dr. Zhivago"? It was released by MGM during the label's "Sounds Great In Stereo" era. They'd put that statement on the record jacket whether or not what was inside was really recorded in stereo. "It would sound great if it had been recorded in stereo, but unfortunately, it wasn't, " is what MGM meant to put on the cover, I'm sure, but they probably didn't have room.

The "Dr. Zhivago" track was recorded in genuine stereo. Unfortunately, it sounds as if it was recorded in the hanger belonging to the genuine Goodyear Blimp instead of on a scoring stage. Soundtrack LPs were "iffy" in those days, even when the original score sounded good in the movies on a 70MM six track magnetic soundtrack. And some LPswere great: check out the soundtrack to "How The West Was Won' (MGM 1SE5 LP), and of course there are Mancini's "Living Stereo" soundtrack albums.

The advent of Dolby stereo in the 1970's meant that a single compatible mono/stereo optical print could be struck playable in any movie theater. Studios began paying more attention to the sound quality of the music recordings, and of course stereo became the rule.

During the 1980's, pop music invaded soundtracks: it seemed as if movies were being written around pop tune packages, and indeed that was the case. While that phenomenon continues to spawn top selling CDs ("Sleepless In Seattle", "Forrest Gump" etc.), there has been a resurgence in the popularity of symphonic scores, much to the delight of cinema "traditionalists". The two musical forms can coexist: Epic issued two "Gump" soundtracks- one containing the pop tunes, one the symphonic score.

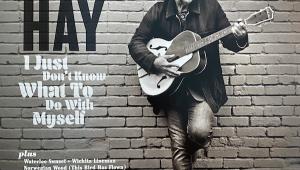

Back in 1981 when I was working at Walt Disney on the soundtrack to "TRON", my path crossed with recording engineer Shawn Murphy. It was nothing more than a perfunctory introduction in a darkened dubbing theater. My next meeting with Murphy was via LP: the 1989 soundtrack to "Glory" (Virgin Movie Music 1-91329 LP). which was reissued by Classic Records on 180g LP. It was and is an astonishing sounding recording: breathtaking in its size, weight, image specificity and dynamic range. "Glory" is a soundtrack any so-called "audiophile" label would be proud to have released.

Murphy has become one of Hollywood's busiest and most respected scoring engineers, having established close working relationships with Hollywood's most sought after composers, including James Horner and John Barry.

The sound on "Glory" was no fluke: Murphy has repeated that magnificent feat repeatedly, recording mostly to analog with just a few microphones. Getting an industry fixated on budgets and production schedules, to accept that minimalist production style was an accomplishment in and of itself, but Murphy's results speak for themselves.

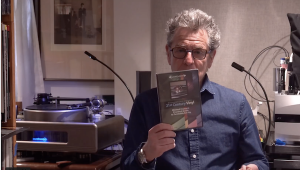

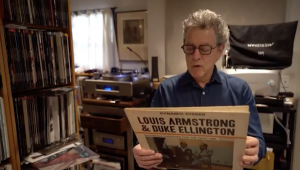

The reason Shawn Murphy strives to produce audiophile quality recordings is simple: Murphy is an audiophile and a music lover. He's got a VPI TNT 3 turntable with a Spotheim SPJ arm and Lyra Clavis cartridge, a Krell KPS 20 CD player, a Jadis JP-80 pre-amp, Belles Labs 1001 amps and a pair of Wilson Audio X-1s. (probably updated since then! -ed.)

There are those in the "number crunching" wing of the engineering community and elsewhere who disparage audiophiles- especially those who like vinyl -as delusional individuals who spend absurd amounts of money to obtain sound at home that bears no relationship to either real music or to what's on that elusive master tape. You've probably heard the argument from digiphiles and "mid-fi" types. Stereophile publishes bitter letters from such individuals all the time.

Recently, during a rare break in his busy schedule, I had a chance to sit down (via telephone) with Shawn Murphy and talk about his work, and his love of music and good sound.

M.F.: The first time that our paths crossed was at Disney back in 1980 or 1981, and you were recording either the digital "Fantasia" replacement soundtrack or "Something Wicked This Way Passes." Is that what you were working on at that point?

S.M.:Probably it was one or both of the above, Yeah. My guess is in '81 we were in preparation for that digital "Fantasia."

M.F.: Which we can talk about in a few minutes, but do me one favor and just trace me the events which led you to be on the Disney lot engineering film scoring sessions back in 1981. Just, you know, some biographical background.

S.M.: Okay. Well it dates back actually to about 1971 or '72 when I was working at Disneyland as a sound supervisor. And this is after all of my educational background complete and a try at teaching university in theater, which is my specialty, at graduate school.

M.F.:Where did you go to school?

S.M.: I went to Stanford - an MFA in theater technology.

M.F.: Oh. So you're a California boy.

S.M.:Yeah. I'm actually a Los Angeles person.

M.F.: Oh.

S.M.:But still I did my university in San Francisco. None of which was officially connected at all with what I'm doing now, as usual. My undergraduate major was history, and I had a pretty heavy involvement with music but no official music degree.

M.F.: Right, but this was something that was always in you?

S.M.: I played musical instruments since I was in third grade. I was a brass player, and I played all the way through college and graduate school and then came to the realization after that time that I was never

gonna make a living at it.

M.F.:And were you a record collector and an audiophile?

S.M.:Always. I was a collector and sort of an infant audiophile, I guess you might say. I was interested in sound equipment and recording all along. And this involvement with theater, connected me technically with lighting and sound, and I took that degree, because I had been interested in theater all along at Stanford. Well, I came to Southern California to teach that and did teach that at Cal Arts for about a year and a half. And then there was the usual cut back where all of the technical theater faculty was let go at one time.

M.F.: What year was that?

S.M.:That was 1973

M.F.: So you weren't a victim of Proposition 13. That came later.

S.M.: No, I think it was just-it's a Disney funded organization, and I think they were just reshuffling their priorities-despite the fact that we had a really terrific program. There were six faculty members and we were all sort of dismissed at the same time. It's still funded by the Disney Foundation Cal Arts, California. Anyway, in the meantime I'd been working at Disneyland and had wound up as a supervisor in the entertainment sound department there, and worked there for a total of almost four years in entertainment sound, parades, special events, wiring sound systems, supervising and making recordings for any live event. Any non-ride oriented sound requirement.

M.F.: Non-ride oriented. So we can't blame you for "It's a Small World After

All?"

S.M.: Uh, please.

M.F.:'Cause if we could, that would be great.

S.M.:It would be great to have the person to blame for it wouldn't it?

M.F.:Yeah it would.

S.M.:So my involvement wasn't directly with the rides, although I wound up in the same department which deals with that as well.

M.F.:How connected was that to the studio itself? Was it a totally separate entity?

S.M.:Well it wasn't very connected at all, but here's the connection for me. While I was working at the park, I met some people who worked at what was then called WED Enterprises (a division of Disney)-the people who designed the amusement park.

M.F.:Right.

S.M.:The rides and and all the engineering. And a couple of people there and I became friends, and ultimately the engineer who I'd met and was working at WED wound up working at the studio, the Disney studio -as the assistant sound department head. We had maintained a friendship all along, and our paths had diverged and crossed again many times since 1973/'74/'75-that area. I had gone on and worked primarily in television, and my specialty in television for many years was reinforcing and recording systems for special event shows such as award shows, big musical specials, things like that. Some of which I just designed systems for, and some of which I mixed. Anyway, we kept track of each other and I had wound up at CBS Television about 1977 or '78, and had been mixing shows there for a few years, and this friend who wound up at Disney studios had inquired as to whether I would be interested in working just occasionally part time as sort of a substitute music recording person at the studio. This was the old Disney regime when the sound department was not a big operation. It was kind of a very friendly small operation, and the same person that was the scoring mixer was also the music re-recording mixer. And he wound up being busy in the theater much of the time as a re-recording mixer, and at that point they needed someone to occasionally substitute as a scoring mixer, and that was where my involvement with the studio started.

M.F.:Now at that point in time Disney was not what you'd call a very active studio as I remember.

S.M.:Very, very much the opposite,. The studio was producing maybe two or three feature films a year. The animation division was, in the mode of producing one picture every two or three years.

M.F.: There wasn't a lot going on. There wasn't much television. Their main emphasis at the point where I became involved, which is 1981 or so, was the Epcot project. And my/my first toe in the water at Disney was to record some tracks for Epcot, and I was brought in just, on a daily basis when I was available to go over there and record individual musicians or orchestras, whatever was required

M.F.Right on the lot?

S.M.:Right on their lot on the scoring stage which was a small stage and it is, kind of thankfully now not in existence anymore, because it was really too small for any kind of major orchestral recording.

M.F.:And I imagine at that time the equipment they had on hand was probably fairly old?

S.M.: Well it's interesting how it wasn't too old but it was pretty antiquated.

M.F.:Yeah, I know, cause when we did "Tron", they didn't have high speed dubbers.

S.M.: They didn't have high speed dubbers for a couple of years after that in fact. It's interesting because they bought some new equipment. I think that when you were there with "Tron" they did have that Harris console, which was a relatively new console.

M.F.:That's right. They made a big deal out of that

S.M.:But they didn't have, you know, anything connected to it which was modern at all.

M.F.:That's why we took the movie off the lot.

S.M.: Yeah you went down to Lion's Gate.

M.F.:You can talk about a friendly sound department, but they weren't too friendly when I did that.

S.M.: Well the funny thing about the friendliness was I think that, in your situation you were very much pushing against the tide at Disney and it was very much a traditional place. It was very much "We've always done it this way, and thisis..."

M.F.:That's right

S.M.:And, "This is old school film," and while there's some valid arguments to the old school film approach for some things, you know, there's also some very good arguments for change and for new techniques.

M.F.:Well they were compressing the dialogue tracks immediately, for one thing.

S.M.:Oh, they were compressing probably everything.

M.F.:They were compressing the rushes (the daily developed picture and sound) and that was it, and that's what was being used.

S.M.:Yeah.

M.F.:I tried to stop that, and it was very difficult.

S.M.:Hard to do, yeah. I mean even multitrack music recording was really not a very common thing there. Most of the music recording prior to 1978, '79 '80 was done straight to film. Three or four track film. No multi-track whatsoever.

M.F.:Well some of our readers are probably saying "Hey, that's good"!

SM: Well if it was done right it probably could be good.

MF: Okay so now let's just talk about "Fantasia" for a minute. I remember being brought to the big mixing stage, and they sat us down and they played us that track.

S.M.: Where at Disney?

M.F.:Yeah, it was at Disney. Now who was the guy in charge ofthat- who conducted the orchestra?

S.M.: Oh, Irwin Kostal.

M.F.: That's right.

S.M. Right. He just passed away about a year ago.

M.F.:Anyway, he sat everybody down and was very enthusiastic about this digital recording.

S.M.: Right.

M.F.: And I wasn't. What was your take on what it sounded like?

S.M.:Well, it was much different from what we had previously heard. You know, it was a new thing, and it was a technology that none of us were very familiar with, and we got familiar on that picture with it.

M.F.:Was that the 3M system?

S.M.:It was the 3M system.

M.F.:Which actually was pretty good from what I've heard from others.

S.M.:Probably one of the best. As we've gone down the digital road it's gotten less and less good.

MF: That was a 50K sampled system?

SM: It was 48 slash 50- the sampling frequency depends on the speed of the machine

M.F.:There were no "digital outs" in those days, so the only way you got a signal out was after it was converted back to analog, correct?

S.M. Well it ultimately did have digital outs, but it was sort of directly on a spigot right off a circuit board. And it could make machine to machine transfers, but it was not in a digital format that any other machine would recognize. It was proprietary and only worked with other 3M machines.

M.F.:When it worked, from what I've been told. Did you have a lot of trouble

with that? Was it exciting working with something like that ?

S.M.: Well it was exciting. I had worked a little bit with it prior to the "Fantasia" project, and it was maddening because the darn thing was very difficult. It wasn't made to synchronize. It wasn't made to operate in the studio environment and it was a problem. It cost us some time. when we discovered that digital copies didn't sound the same as the master.

M.F.:Right.

S.M.:Analog copies off of the machine and back to the converter sounded very different. You know, it was a generation lost at least of the magnitude of an analog generation. It was not a very satisfying situation except the digital world was so new to us that we were sort of in the process of getting used to it and trying to figure what would be the best way to utilize the technology if we could use it at all.

M.F.:Did you find yourself altering your favorite mic positions, and how you miked things?

S.M.:Yeah. I think that was a good and a bad part of that. Because what I wound up hearing was not what I expected sometimes. You would alter microphone selection and pre-amp selection and mic positions to get what you thought was going to be an improvement which ultimately maybe was, maybe wasn't.

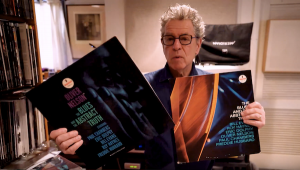

M.F.:Now, speaking of mic positions, when I listened to recordings you've made- I sat down today and played a whole stack and I have to say it certainly was a pleasurable experience-I was amazed at some of the sounds. There's a uniformly great sound on those things, different in each case, but uniformly great. When I listened to these orchestral recordings, I'm reminded of the big wide sound stage recordings that Kenneth Wilkinson used to create for Decca. Is there any similarity to how you mike things? You are familiar with what he did?

S.M.:Yeah, I'm very familiar with it, and you basically hit the nail on the head in terms of the style that I have been emulating. That's it. I mean it's a "Decca tree" and it's outriggers, and very little else.

M.F.:So explain that to our readers who aren't familiar with what that is.

S.M.:Sure. Well a Decca tree is a system that Decca Records developed and Kenneth Wilkinson was probably the engineer most responsible for the Decca tree's configuration in stereo recordings. It consists of three microphones in a triangular array that are positioned directly over the podium. The microphone type that was used primarily was the Neumann N50 in the Decca tree, and that is a mike which was omni-directional at low frequencies and becomes increasingly directional with frequency so that whereas at 100 Hz or less or even up to 1,000 Hz. you have basically an omnidirectional pattern. At 5 kilohertz you have a tightening of the pattern, and at 10 kilohertz and above you have what's essentially a cardiod to hypercardiod microphone which gives you the ability to pick up a sound at distance with some specificity. It gives you the ability to reach a little bit at higher frequencies as opposed to having a diffused sound field of high frequency.

M.F.:Well the image specificity on these recordings is absolutely astounding. The detail.

S.M.:Right. A lot of that has to do with the M50. The M50 is a tube microphone and it also has let's say a boosted low frequency performance, but an enhanced low frequency performance, in that it has a big warm extended low end.

M.F.:Well, that's also on these CDs. I mean the bass response is absolutely astounding.

S.M.:Right.

M.F.:It's superb.

S.M.:And it has a slightly rising frequency response characteristic starting at- depending on the type of M50, there are a number of different types of M50's around- but sometimes as low as one kilohertz- but always by five kilohertz, a rising characteristic so that you get a response peak somewhere in the 10 to 12 kilohertz range, and then a shelf and slow attenuation of high frequencies above 15 kilohertz, which gives you a very extended smooth high end, again with a little extra reach.

MF: Now you're using those M50s?

S.M.:Yeah, I have six M50s of my own. You'll find that there are a lot of good engineers that are using M50s now as their basic room pickup. The spacing of the M50s is variable and it's sometimes as wide as a six foot triangle, and sometimes as narrow as a thirty inch triangle depending on the room, depending on the kind of image you're going for. The height of the tree varies from eight and a half to twelve and a half or even thirteen feet, depending on the room and the acoustics.

M.F.:Now you mentioned outriggers. Those are extra microphones?

S.M.:Two additional mikes that are sometimes referred to as outriggers and sometimes referred to as string boosters. They are hung- spaced to the left and right of the tree, to the left and right of the podium over the first and second violins on the left, and over the viola, celli on the right. They are angled slightly downward in relation to the tree and hung basically in the same plane as the back two mikes on the tree, so that it creates a four mike array: two outriggers and two that are on the tree that are in a straight line across the front of the orchestra. The tree elevation being let's say eleven feet, the outriggers might be eleven, or they might be slightly lower. They might be ten or 10 and a half feet.

M.F. The low bass string instruments dig in so deeply and so fully, you get it right through your gut.

S.M.:Yeah. It increases the detail and the level of the low frequency information, and of course, the high strings as well. Now the outriggers are not always M50s, although in the Decca system, they often were.

Sometimes they're M49s, which is a cardioid version of the M50 using the old U47 capsule and an AT701 tube. Sometimes I use C12s as outriggers, and I use those in various capsule pattern configurations. Omni sometimes, cardioid sometimes, wide cardioid sometimes. I've also used solid state mikes such as TLM50s and Schoeps as outriggers.

M.F.:You ever play around with pressures zone (PZM) microphones?

S.M.:I have. I have found those to be useful in some close miking situations but not so much for room miking.

M.F.:Uh huh. Like on a piano?

S.M.:Well, I've tried them on piano and have been successful in some cases. I've put them inside a bass section just as a section booster. I've put them on the floor in front of woodwinds a few times, and I've used them in percussion sections a few times.

M.F.:I kind of lucked out because I happened to have been playing a Chesky vinyl issue of a Wilkinson recording of "Film Score". I played that just the other night and satdown with some of the CDs you recorded and said "Gee, you know, this is great!"

S.M.:Well, I think his recordings sound terrific.

M.F.:Shawn, when you first started doing this, given what most producers, certainly in the film industry we're used to with recordings, you know, sticking a microphone into everything- first of all how were you met when you proposedm or started using a few microphones hanging on this contraption?

S.M.:Well, I started doing this before I worked at Disney. I actually did some radio recording back in the mid to late '60's and early '70's when I tried this technique out and liked it. I didn't have much opportunity to do it when I worked in television, for obvious reasons. When I had the chance I would

put this kind of room pickup into operation whether or not I would also put up a lot of close mikes. Now you're absolutely right that the prevailing sound at the time was not this. It was a lot of microphones and a

very much in-your-face kind of approach to the recording which I never much liked.

M.F.:Well, yeah, especially given that everything is mix, mix, mix in Hollywood. I mean everything is a mix down from umpteen different elements.

S.M.:Yeah, it's true. I think that a lot of it has to do, of course, with the composer. What you find is certain composers are more receptive both then and now to trying a new way of doing it and opening their ears up a little bit, and some are very much unresponsive. As you know,I've worked with James Horner a lot, and he's been very much in favor of this approach.

M.F.:And John Barry?

S.M.:And John Barry and John Williams.

M.F.:You can hear it in those recordings, but how much control does the composer have, and how much control does a producer or a music supervisor who's sitting on a tight budget and wants to be able to fix it all in the

mix?

S.M.:Well we just don't give them any control!

M.F.:At this point you have that leverage, but did you always?

S.M.:Yeah, I think the composer has always had that leverage. I mean certain newer or younger composers may be less willing to exercise it, but when they hear the results, they often are willing to exert a little pressure. Sure we've had the request all the time from directors and producers and music supervisors, you know, "We want to be able to isolate the percussions. We want to be able to isolate that solo instrument." And whatI always say to them is "We're making an orchestral recording here, and if there's a very important dramatic reason or sound mixing reason that we should isolate

something, let's plan ahead and try to do it in such a way so that the recording doesn't suffer." So that the overall musical effect is still one of an orchestra playing in a real room all at the same time. And, let's try to think about this because, really the technique I like to do, and the technique that most of the composers that I work with would prefer is one where everyone performs in the same room at the same time and there isn't much isolation.

M.F.:That's what gives it that that live quality, that sensation that it's big, and it's right in front of you, which you get.

S.M.:No question about it.

M.F.:Now when the feed comes from those mics, what kind of mixing desk

are you using?

S.M.:Well, I'm now at the point where most of the microphones are fed directly to the multi-track machine via outboard pre-amps.

M.F.:Each to it's own track?

S.M.:Each, well usually each to its own track. A few tracks get mixed and then I'll use a Nieve console to mix together those signals, but what I usually do is to make a live mix at the same time not going through the machine. So that I have basically the output of the pre-amps going to two locations at once. One is to the multi-track machine for later mixing if necessary, and the other is straightto the Nieve console to make a monitor mix. Now in a lot of cases, and I would say with John Barry and John Williams, the majority of the cases, what you get is a lot of mix.

M.F.:What you end up using is the monitor mix?

S.M.:Absolutely. What you get on the CD and in the film is the mix that was created at the session, at the time and is not altered in any way.

M.F.:To how many tracks?

S.M.:Usually to five which is a three-track mix: left, center, right plus stereo surround. And that's it. That's the beginning and end of the story.

M.F.:Stereo surround?

S.M.:Stereo surround.

M.F.:Okay, when they mix that down for a Pro-logic mix, what do they do?

S.M.:They make the surround mode at that point, because it goes through a 4-2-4 ( four channels to two, and back to four Dolby) matrix.

M.F.:Now we're gonna have AC-3, so we're gonna have five lousy tracks instead of three good ones.

S.M.:Right. You're gonna have five digitally compressed tracks.

M.F.:Right. What do you think about this?

S.M.:Well, you know, so far the demonstrations I've heard of

AC-3 have not been too effective.

M.F.:Same here.

S.M.:But, you know, I'm willing to give it a chance and maybe someone can impress me, but, you know, simply 5.1discreet is very good.

M.F.:Right.

S.M.:You know what goes into a 5.1 system coming off a dubbing stage is very, very good. So,hopefully, we can get closer to that in our deliveries.

M.F.:Well it seems to me that when you're watching a movie in a movie theater that's on an optical Dolby track, you're losing a lot in the other regard.

S.M.:Right.

M.F.:So with an AC-3 digital mix in a theater, you're benefiting from the extra dynamics and everything else.

S.M.:I think all these digital systems are a trade-off because you're right, going to the 4-2-4 matrix is a fairly destructive thing, particularly to the music.

M.F.:Especially on an optical track.

S.M.:Especially when it's optical, although a very well produced SR (Dolby Spectral Record) optical track is actually pretty good. One could argue that it is-just as an example on the "Hook" score, which I recorded, as well as re-recorded, we made three masters. We made a Dolby A discrete which went to six track mag 70MM, which was basically a 5.1 channel dub.

M.F.:Well those were the days, Shawn.

S.M.:That was Dolby A though. Then we made an SR optical, and then we made a Dolby A optical, and I could argue pretty strongly that the SR optical was better sounding than the Dolby A mag.

M.F.:Wow.

S.M.:Mainly because of the limited dynamic range of the 100 Nanoweber mag track, and the Dolby A noise reduction which is less than perfect. Now I can tell you that after playing back100 times there's no question that the SR optical would be better.

M.F. :Oxides's being shaved off every play.

S.M.:Yeah the mag is just not gonna hold up very well.

M.F.:Now once you've got this mix down, what are you recording on, analog or digital? I know many of them are analog, but.....

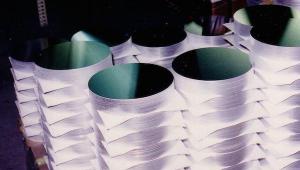

S.M.:Most of them are analog. The orchestral recordings are virtually all analog now, and I went through that period when you and I first met, of (trying)the 3M digital machine and the Mitsubishi digital machine, and the Sony digital machine, and I tried them all through consoles and with outboard pre-amps and with various kinds of setups and wound up going back to multi-track analog pretty quickly.

M.F.:What machine do you use?

S.M.:Well, it's usually a Studer.

S.M.:It varies with studios and we typically we either use Studer A-27's, A-20's or A-800's. Occasionally we'll run into an ATR 124 which is a particularly nice old machine. Not very many of those around. Usually at 15 inches per second. Usually with Dolby SR noise reduction and usually without elevating the level. There's an argument which says that format really gives you more dynamic range than 16 bit digital, and it certainly gives you better sound quality in the recording if you're executing it right.

M.F.:Well I noticed that a few of the recordings had "DDD” on them, I think "Bopha"?

S.M.:Yeah "Bopha". That's not an orchestral recording though. That's the synth score. Now most of the synth scores that I do are done on a Sony 48-track digital machine. Partly, of course, because the source material is often synthesizers and samplers anyway. So the source material itself is not necessarily any better than 16 bit digital, and I think the rationale for doing that is one of convenience and practicality when you're doing synth and overdub scoring and lashing up a lot of tracks. You may at some point have two 48-track machines working. You need to be able to bounce tracks, combine tracks and make digital edits. You need to be able to have a relatively expedient session in terms of punching in, and punching out. And that's where digital really comes in handy. It's very, very fast and production friendly.

M.F.:Do you read scripts and change your miking choices based on the emotional needs of the film, or do you depend upon the director or the composer to communicate those things to you?

S.M.:Well I virtually never read a script before I work on a show. I always talk to the composer before we record a score to find out what his intentions are, and we always try to coordinate our production plan and our musical plan both so that we can get things done on schedule and with the most efficiency, and so that we wind up with the kind of sound we want. But this is usually between myself and the composer and sometimes the orchestrator. The orchestrator is a very key figure in all of this.

---End of Part I--