The musicangle interview: Joe Boyd

As with the music, Boyd's tasteful production and John Wood's no nonsense engineering have passed the test of time. The consistently fine sonics on those records, evident even on the primitive turntables of the sixties, are greater treasures today.

Wood's recordings are spacious, dimensional, dynamic and natural. He knew how to mike acoustic instruments and he respected the power and communicative abilities of the unadulterated human voice.

The original British "pink label" and "rainbow" Island pressings of Fairport, Drake, Thompson et.al., though hard to find and expensive , are worth seeking out for their superior sound and fine packaging. The American issues on A&M pale by comparison. For some reason, that goes for all of the Island catalogue released by A&M. Warner Brothers did a somewhat better job with the Island material they licensed- Richard Thompson's Henry The Human Fly for example.

During the eighties, Boyd's Carthage Records reissued much of this material on vinyl, mastered both at Sterling Sound and Masterdisk, with mixed though mostly positive results. Also during this period, Boyd's Hannibal Records released three new Richard Thompson records: Shoot Out The Lights (a gold CD reissue was reviewed in TTA #1), Hand Of Kindness, and the very hard to find Small Town Romance - a compilation of two solo acoustic sets recorded in the fall of 1982 in New York City at The Bottom Line and Folk City. It was withdrawn from the market due to Thompson's discomfort with the preservation of mistakes inherent in live solo performances . Rykodisc, which acquired the Carthage/Hannibal catalogue, has been reissuing the Thompson catalogue and much of Boyd's other productions on CD, also with mixed sonic results.

The self-effacing Boyd failed to mention during the course of our interview that he produced the documentary film Jimi Hendrix (1973), as well as R.E.M.'s Fables Of The Reconstruction, and 10,000 Maniac's Wishing Chair . You'll also see his name on the soundtrack album to A Clockwork Orange .

Boyd now runs Rykodisc Europe out of its London office. He's still involved in producing records for Hannibal, with the emphasis on ethnic and "world" music.

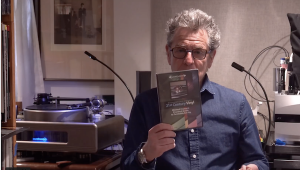

Being an appreciative fan of Boyd's work for over twenty years, and knowing nothing whatsoever about the man, when an interview opportunity presented itself, I went for it.

I was a college student when I started buying Boyd produced albums, so I was expecting an older, distinguished sort of British gentleman. Boyd turned out to be in his early fifties, and a native of New Jersey. His conversation was as straightforward, honest and enjoyable as his production.

MF: Twenty years ago when I was in college, your name was on many of my favorite records. You don't look much older than me, so when did you begin producing records?

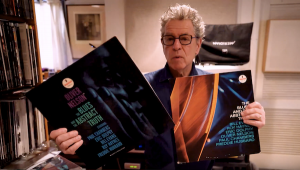

JB: I was a blues and jazz buff in my teens and when I went to college in the early sixties at Harvard, it was a good place to be, surrounded by the folk scene, I started distributing record labels from my dorm room- Folk Lyric, Folk Legacy, Arhoolie, Delmark- that kind of thing.

MF: What made you do that? Didn't the Harvard Coop have those recordings?

JB: No. This was 1962 they didn't have that kind of stuff. The watershed moment where you realize you can transfer your fantasies into reality and that basically what you have to do is pick up a telephone and knock on a door- was when we- my brother and Geoff Muldaur - I grew up with him- we'd spend the whole saturday afternoon listening to every single solo by Johnny Dodds in chronological order- things like that.

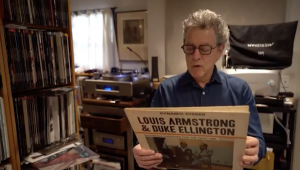

My brother had heard over a Philadelphia radio station- Chris Albertson had a jazz show - and he happened to mention that he'd heard that Lonnie Johnson, who'd disappeared in the fifties, was working as a cook in a hotel in Philadelphia. And Lonnie Johnson was one of our favorites. He had all these different careers as a blues singer on Bluebird, and jazz guitar with Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, and those duets with Eddie Lang. He did incredible things. He had a hit as late as the fifties- "Tomorrow Night" on King. And then he disappeared.

We went and got the telephone directory and went to "Johnson L" and started dialing. The third one, there was this elderly male voice and we said "Are you Lonnie Johnson?". And he said "yes". And we said, "Are you the Lonnie Johnson who recorded "Blue Goes Blues" for Bluebird in 1936?" And he goes "Yes". So we invited him to come to Princeton to do a gig. We offered him fifty dollars because that's all we could afford.

So we said we'd come down to pick him up, and we got all of our friends to promise to pay a dollar each. And it was an unbelievable experience. He was great! And subsequently Chris Albertson made a record for Bluesville, and Johnson started doing the revival circuit. That was the moment you realize you could actually make contact with the real world and do real things, not just sit there and live through records, listening and fantasizing.

MF: How did you get to England?

JB: Well, to make a long story short, I took a year off from Harvard, and went to Los Angeles and started knocking on doors. And I knocked on the door of Les Koenig's office who ran Contemporary Good Time Jazz and asked for a job... . He'd left Dartmouth in the middle of his sophomore year to go on the road as a band boy for Count Basie, so he identified and sort of patted me on the head and gave me a job as an office boy during my year off.

And I heard Phil Elwood had a jazz show on Pacifica radio and I had all these tapes from old 78s and I thought Phil Elwood would be out at the radio station so I went there looking for him, figuring we could swap tapes, but of course he wasn't there, he was in San Francisco because it was syndicated. I was totally naive, it was totally insane. But at the end of the afternoon of looking for Phil Elwood, I had an invitation to do my own show on KPFK Pacifica, which was network.

MF: See how easy life is for some people?

JB: Well, the same thing happened with Europe. I wanted to go to Europe. Europe was like a nirvana of reissue. Blind Boy Fuller records on English Phillips. RCA deleted the old ten inchers.

MF: So how did you go from the Black jazz and blues stuff to folk music and Island records?

JB: I ended up getting a job taking a blues and gospel tour to Europe. Muddy Waters, Reverend Gary Davis, Brownie and Sonny. They needed a tour manager, I had put on concerts in Boston and I was known to Manny Greenhill who was the big concert promoter at the time. He'd hired me once to look after Jesse Fuller for a weekend-keep him sober and get him to the gig on time.

MF: So while in college, you were not only selling records, you were putting on concerts.

JB: Yes. I'd blow all the money I made doing records, bringing in people like Big Joe Williams. We had three hundred people to see Lightning Hopkins. But I was known as a person who had a history of getting a blues singer sober and on time to a concert. So Manny recommended me to George Wein who hired me to take this tour to Europe. And I got there and from three hundred people coming to see Lightning Hopkins in Boston, there were three thousand people in Bristol and teenage girls waiting backstage for Muddy Water's autograph, and like it was a completely different world! I said this is the audience that likes what I like. It was a very exciting time to be in England, so I decided to stay. This was 1964- 65.

MF: So the whole pop thing was exploding then too. How did you relate to that?

JB: I was very excited by it. I met some people in folk clubs in London. Blues clubs and Folk clubs were in the same pubs. And I met this weird guy and he said "I want to show you something". And he took me to see the Ian Campbell folk group with Dave Swarbrick on violin (later with Fairport Convention). And that really blew me away. And of course the footnote to that is I ended up spending some time in Birmingham with Ian Campbell's family and travelling around with them to gigs and exploring English folk music. And he had these twin sons about four years old, and I used to take them to the park and push the swings. And that's of course Ali Campbell and his brother from UB 40!

And of course I met The Watersons and I went around Scotland and met all these different people and slowly absorbed English folk music. To answer your previous question of how did I relate to the pop stuff that was happening, I saw that alot of stuff was really interesting. A friend of Ian Campbell's took me to a pub in Birmingham where I saw the fifteen year old Steve Winwood singing with the Spencer Davis group doing old Ledbelly songs with a rock band!

And I went back on my next trip to New York, and got together with (the late) Paul Rothchild (producer of the Doors etc.), who was a friend of mine, and said "hey, there's something going on here". We really ought to take some of these folk singers and put them together with a rhythm section. And we actually put together a band with John Sebastian, Zal, Yanovsky, Jesse Colin Young, Jerry Yester and somebody else and had them together for two weeks rehearsing as a band, and Paul was going to record them. But then they broke up, and some of them eventually got together and formed The Lovin' Spoonful.

But the fact that they felt obliged to Paul for what he and I put together, is why Elektra got those four tracks on the "What's Shakin'" album. That was like a payback favor even though they signed with Kama Sutra because they didn't think Elektra was a pop label at that time.

But then, I knew that Paul and I were very frustrated by our failure with that band, and I was working for George Wein and I had to go out to Chicago to do a college bookers convention and sell them Muddy Waters and the same package we had in Europe. And I had already run into Jac Holzman (founder of Elektra Records) at a party when I was drunk and told him what I thought of his European distribution, which was shit. The records were twice as expensive, and you couldn't find them anyplace. So he got very huffy.

Then I ran into Sam Charters (producer for Vanguard) at the Gaslight where Son House was playing. And I said I'm going to Chicago tomorrow, is there anyone I should check out. And he said, well do you want to see the best blues band in Chicago at the moment, because you probably don't know who they are. And I said come on Sam I know about Otis Rush, and I know about Buddy Guy and Junior Wells and Magic Sam, and I know where they play. And he said its none of those. And they're playing on the North side, not the South and they've got White people playing. I said come on Sam you must be kidding. And he said no, its The Paul Butterfield Band. So I called up Rothchild and I told him about them. And Paul said I'll be there. And Paul signed them immediately. And I suggested we go see Mike Bloomfield-he wasn't in the band. And I persuaded Butterfield to jam with Bloomfield's band and the result was Bloomfield was asked to join the Butterfield Band.

So Elektra owed me one. Five months later Rothchild said get up here I've set up a meeting with Jac (Holzman). So I went in there and he said "I remember you, you're that burnt guy from the party. Well here's your chance to put it right. Do you want to go to London and represent Elektra? So that's how I ended up living in England working in the record business. I had been going back and forth and didn't really have a job.

MF: You set up Witchseason Productions then?

JB: After Jac and I fell out. I was with Elektra for a year. I brought The Incredible String Band for Elektra and a few other things. I tried...I brought them The Pink Floyd, The Move, Eric Clapton and Holzman wouldn't sign any of them.

MF: Aargh!!!!

JB: And so there was a lot of antagonism and mutual resentment and ego battles, and I really wasn't on a level to have ego battles with Jac Holzman. And so after I left, I decided to stay, and I started to manage The String Band, and of course I was involved with the musical "underground". And to me there was nothing weird about listening to Muddy Waters one minute and Dave Swarbrick or Syd Barrett the next. It was all music and I only responded to it if it was interesting.

MF: Now John Wood is an engineer you've worked with a lot. Did he engineer the Incredible String Band albums?

JB: Yea.

MF: Those are wonderful sounding records. What was your input on the sound, because all the records you produced, have great sound. They sound better than most records being produced today.

JB: I owe a lot of that to John. It was just chance. When I was working for Elektra, Jac Holzman had a little sideline, it was the first mood music for astrological signs. It was a whole series, Zodiac something or other- twelve disks and there was a contractor arranger because string players were really good and cheap in England those days, about 12 pounds a three hour session. He used to come over and record these things in London. And Jac would call and say he's coming over, would you please help him because they're Elektra sessions. Would you book the studio, handle the paper work etc.

And this contractor always used this little studio in Chelsea called Sound Techniques. And it was a studio that did mostly mood music, some classical stuff, just an ordinary non rock and roll type studio. So I went down the first day to make sure everything was okay, and that's when I first met John Wood and I liked him and I liked the look of the place. So when I had the first Incredible String Band record to record, or a Dave Swarbrick/ Martin Carthy album I don't remember which. Anyway, John, who was a very good classical engineer- he'd started out as an editor at Decca, and he'd been in mastering and maintenance.

So John had never recorded anything remotely like what I was doing, and I'd never produced a record really, so we were both learning and I had a clear mental image of how things should sound like, and he had his training. So I learned a tremendous amount from him and vice-versa. And he just thought this was the weirdest stuff he'd ever heard, but eventually he got to like it. About three years later I was block booking it -doing everything there.

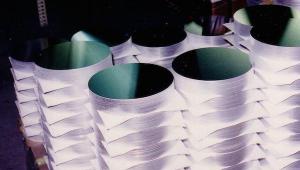

MF: Who was mastering these records?

JB: George Peckham ("another Porky Prime Cut- Pecko Duck) and Malcolm Addey. They were at Pye and then Apple set up a mastering room. But we liked to mix here (in the U.S), and the later stuff we'd take our four tracks and transfer to eight and finish it off at Olympic and mix it at Morgan and then we discovered Vanguard here and they had the most wonderful EMT plate. So it got to the point where in 1969 and 1970 we'd record at Sound Techniques and just come to New York at 23rd street next to the Chelsea Hotel at Vanguard, and we'd move into the Chelsea and mix next door.

MF: Those original pink label Island records, nothing touches those. You have to hear some of those. When A&M bought the Island catalogue? Terrible! How did you hook up with Island?

JB: I started the production company and I had to deal with Polydor for the first Fairport Convention and they were going through a lot of changes. I got very unhappy. I hadn't signed the deal yet. One thing led to another. I met Chris Blackwell (Island's founder), I paid Polydor back all the money and left. It was a very good association with Island. In fact it was nostalgia on both of our parts that led to Hannibal starting as an Island label. Unfortunately it was ten years later, and things didn't work out so well. Eventually I left.

MF: You recorded all the Fairport and Richard Thompson albums?

JB: During the Witchseason/ Island years? Yes. We recorded Nick Drake too.

MF: Do you know what kind of equipment you had at Sound Techniques?

JB: They had their own board. In fact Elektra was so enamored of them they built the board for Elektra's studio in L.A. .

MF: Was that all tube stuff?

JB: Probably, yea. We had Studer two tracks. The multitrack was a 3M at first and then a Studer when it went eight track.

MF: Do you use the same recording techniques now? That record of Bulgarian folk music sounds pretty good.

JB: Well, that was different. I took a classical recording engineer and we went straight to an F-1 and we horrified the Bulgarians by placing them in a circle around a stereo pair. They weren't used to doing things that way. Neither was I, but it turned out very well.

MF: For a digital recording it sure did. Have you experimented much with multitrack digital recorders?

JB: No. I've never done that. What I have done, which I think is okay, although I generally share your cynicism about digital. I don't like the transparency.

MF: There is none.

JB: I think there's too much. I like things to be solid, to be there.

MF: There's no body. Things just float off into nothingness. There's no low level resolution. You can't place things in space. I think we're using the word "transparency" in different contexts.

JB: I agree. I did one record for Virgin a jazz big band album at Angel on Telcom noise reduction- a new system. I was impressed.

MF: Is it like Dolby SR?

JB: I havn't heard that, but I really don't like Dolby. I've never worked multitrack digital and I have no interest in doing it.

MF: Have you heard any CD reissues of your records?

JB: The only ones I've listened to carefully- some of the ones on Hannibal, Shoot Out The Lights those are pretty accurate. I havn't heard the Fairport stuff, but I have heard the Nick Drake stuff, which I think they did well because a guy named John Dent who used to work at Sound Clinic- which used to be part of Island. And now he's got his own place. ...So generally I've changed the way I work a little bit because in the late sixties early seventies I progressively got into working in a very layered way- taking a lot of time with things, but I've really gotten burnt out with that way of working. At Hannibal we don't have the money, so we have to do things live in the studio as much as possible.

MF: Were you upset when Richard Thompson left you for Polygram? (He's now with Capitol/EMI)

JB: No. I had a two record deal with him, and Hand of Kindness is a record I really love...

MF: Me too.

JB: And we really went after it in America. We'd done very well with Shoot Out The Lights when we were very disorganized- no promotion, no distribution and we still sold over 100,000 records. And so we were better organized when Hand Of Kindness came out and we thought, lets really go for it. And we almost bankrupt the company, because we spent a lot more for promotion and we sold only half as many records. And I wasn't sure we could afford to keep the American office open. And so Richard was beginning to reach what could be perceived at the time as a still upward curve, although as it turns out Polydor was unable to sell any more records than we were. But it looked at the time as if he needed a big record company in America. And I didn't even have the money at the time to make the next record. So the fact that Polydor came in and paid me in advance to produce it, and paid Richard a big advance... .

MF: Its a much more commercial, flashy, multitrack sounding record.

JB: Exactly, well we had more time to spend on it. But I knew at the time Polydor wanted something flashier and I felt pleased with the record, Across A Crowded Room because I felt it walked the tightrope. It was a lot slicker than Hand Of Kindness , but I don't feel it comromised Richard's sound or Richard's music.

MF: What's he like working with in the studio?

JB: He's great. He couldn't be easier.

MF: I interviewed him, and it was tough!

JB: He's not a forthcoming kind of guy.

MF: I did Richard and Linda in two different hotels, the same day.

JB: Oy!

MF: What are your favorite records that you produced?

JB: Nick Drake's Bryter Layter , the first McGarrigles record and Reggae Got Soul - Toots and The Maytals. I think that's actually my favorite record of them all. Partly that's because I think I'm a frustrated dance music producer in the sense that I've been identified with much folkier, more intellectual, much more so called middle class white music.