Preservation Hall: Back to the Future, Pt. 1

The MMJ gig is one of many changes happening at the world-renowned French Quarter home to New Orleans jazz, all part of an historic attempt to forge a new identity as the Hall approaches its 50th anniversary and looks forward to a new life in the 21st century.Our Man in New Orleans, Roger Hahn, has the full story.

Part I

Ben Jaffe, the wooly-haired son of Preservation Hall founders Allan and Sandra Jaffe, remembers the exact moment he was converted to traditional New Orleans jazz. It occurred in May 1993, during rehearsals for his senior recital at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. By then he’d formed his own band, had been playing professionally on a steady basis for a couple of years, and had even begun formulating a strategy to win a major-label recording contract.

The band, named No Evidence, was a septet whose name derived from the Thelonious Monk composition “Evidence”. Repertoire consisted mainly of modern-jazz classics and the band’s own compositions. Members all wore sharp business suits and ultra-cool ties. Jaffe played string bass and managed the band, setting up gigs, overseeing road trips and working out the finances. During the previous two years, the band had played gigs throughout the Great Lakes region, from Columbus to Pittsburgh, Detroit to Buffalo.

Jaffe regarded the recital as a kind of professional showcase, demonstrating the skills of the musicians and their expertise playing a wide range of numbers. Just for good measure, he thought, why not end with a flourish and wrap things up with a good, old-fashioned New Orleans funeral march? At their final rehearsal, Jaffe suggested the band run through a couple of traditional New Orleans tunes, “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” and “When the Saints go Marching in.”

He counted off the time and waited for the traditional snare-drum roll. It never came. Neither did the street-march trumpet flourish to kick off “When the Saints.” The band, in fact, had neither heard traditional New Orleans jazz, nor did it know any of the timeworn traditions associated with the music. Jaffe was stunned. He’d grown up with traditional New Orleans jazz. It was in his blood. He couldn’t imagine some of the best-educated young musicians in America having no knowledge of it whatsoever.At that moment, he felt he was witnessing a very real clash of cultures.

Celebrating Jazz Roots on the Way to Dixieland

In the beginning, Preservation Hall was just an informal gathering of traditional jazz fans where some of the old-time musicians could play for tips on a Sunday afternoon. The musicians, the majority of them quite elderly by then, were mainly survivors of an earlier age, remnants of the dancehalls and neighborhood clubs that had once been popular throughout the city of New Orleans. By the late 1930s, however, the number of professional gigs featuring old-time jazz had been reduced to less than a handful. According the "WPA Guide to New Orleans," published in 1938, the music was by then “nearly extinct.”

What brought it back was an underground movement of record collectors almost-religiously devoted to “hot” jazz—the small-ensemble style predominant before big bands and highly commercialized swing music came to dominate American culture. The collectors—ardent archivists, intellectual mavericks, and impassioned college students—found in the old music a more genuine, more moving form of musical expression. By the late 1930s, this loosely organized underground movement succeeded in producing the first credible jazz history (“Jazzmen – The Story of Hot Jazz Told in the Lives of the Men Who Created It,” published in 1939).

Research for the book led to the discovery of Bunk Johnson, a trumpeter once well-know in New Orleans but now living in semi-retirement in New Iberia, a quiet town surrounded by fields of rice and sugar cane approximately 100 miles west of New Orleans. Believing Johnson represented a direct link to the birth of jazz, the researchers decided, especially with the likelihood of World War Two looming, that Johnson had to be recorded, providing a priceless document of a world that existed before the widespread advent of recorded music.

The recordings of Johnson, made on makeshift equipment in hastily borrowed rooms, helped ignite a firestorm of activity within a larger circle of connoisseurs, leading to a series of concerts in San Francisco, Boston, and New York City. By then Johnson had become a “hip” celebrity, gracing the covers of leading fashion magazines, the founding figure of what was, essentially, the first American “roots” revival. After his death in 1949, Johnson’s band, led by clarinetist George Lewis, continued carrying the torch for what eventually became known as the traditional New Orleans jazz revival.

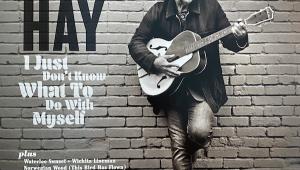

During the 1950s, the traditional New Orleans jazz revival pressed forward in fits and starts. The primary impulse behind it had been transferred to England, where the music thrived as a postwar soundtrack to newly disillusioned British youth and anti-war activists, including those who first popularized the graphic design we now associate mainly with the Sixties, the universal “peace symbol.” In America, the music was eventually absorbed by mainstream culture as Dixieland music and by the end of the decade had produced two nationally recognized “stars,” Pete Fountain and Al Hirt.

A Home for New Orleans Jazz in the French Quarter

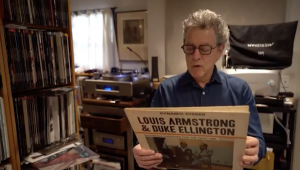

In New Orleans, its acceptance was more tenuous. At the heart of the New Orleans jazz revival was a widely shared new appreciation for African-American music of the early 20th century, including the small-combo jazz Louis Armstrong was now playing, the burlesque-style early blues of Bessie Smith, and authentic gospel music as performed most prominently by New Orleans native Mahalia Jackson. In postwar America, a new appreciation for black music signified the kind of enlightened outlook that would, by mid-decade, bring about court-enforced, public school desegregation.

In the 1950s, New Orleans was still recognized a symbolic capital of the Old South, holding fast to the old Jim Crow laws, insisting that whites remain in control and blacks remain apart. Under these conditions, the world of traditional New Orleans jazz stayed mostly underground, surviving on the fringes of the black community and among a small cadre of outsiders in the French Quarter, among them figures like Larry Borenstein, an art gallery proprietor and real estate owner of Russian Jewish descent, and Bill Russell, one of the original jazz historians, an eccentric classical composer and unrelenting hoarder of jazz memorabilia who hailed from rural Missouri.

Some of the strongest support for the traditional New Orleans jazz revival came from Northern intellectuals and English musicians who fervently collected early jazz records and through them had learned to play New Orleans jazz. All eventually made their pilgrimage to the French Quarter, seeking out “the real stuff.” By the mid-1950s the journey to the jazz mecca had become a not-uncommon ritual and insiders had gotten the word that Bill Russell’s little record shop in the French Quarter—almost directly across the street from where Preservation Hall now stand—was the place to go to find out who was playing where that night and who might be playing later in the week.

By the early 1960s, two national record labels, Riverside and Atlantic, arrived to record an extended series of performances by a variety of artists, and small labels were launched to document their own perspective. Around the same time, the audience attending the informal Sunday afternoon performances at Larry Borenstein’s art gallery on St. Peter Street now extended well beyond “a small circle of friends.”

If they were to continue as a regular fixture of the traditional New Orleans jazz revival in the French Quarter, someone else would have to organize them. Borenstein chose Allan and Sandra Jaffe, a young couple recently arrived in New Orleans.

For their honeymoon, the Jaffes planned to travel around the country looking for somewhere to settle. New Orleans was the first place they visited. Both had musical backgrounds, both were obviously intelligent and capable, and both had fallen in love with the traditional New Orleans jazz scene in the French Quarter. Their ascendance caused a falling out among the loyalists drawn to Borenstein’s gallery; as the Jaffes began the attempt to extend the gallery jam sessions into a self-supporting venture, competitors sprung up immediately across the street and several blocks away. But it was the operation Jaffe decided to call Preservation Hall that survived.

Building the Foundation for Long-Term Preservation

“We didn’t have any big bang at first,” Allan Jaffe told “The New Yorker” jazz writer Whitney Balliett in 1966. “New Orleans doesn’t support its own music. It took two years just break even on a month-to-month basis.” During those first two years, both Jaffes held down full-time jobs and tended to the Hall at night. Jazz historian Bill Russell became an ad hoc adviser. Volunteers from the informal art-gallery sessions signed on as ad hoc staff members. Some nights, the Jaffes, Bill Russell, and a couple of volunteers intentionally sat in front listening to the band so any passersby would think there was already a small audience inside. If they failed to make enough at the door to pay the musicians union scale, the Jaffes made up the difference themselves.

Along the way, Allan Jaffe was creating the foundation for Preservation Hall, developing a management style that created an intrinsic structure—choosing musicians, arranging performance times, marketing the Hall—while taking a decidedly laissez-faire attitude the rest of the time. It’s a management style one could easily mistake for no style at all, but Allan Jaffe knew exactly what he was doing as he created a structure and atmosphere that would sustain Preservation Hall for 50 years. The heart of his philosophy centered on the musicians. As soon as he began enlisting musicians to play at the Hall, he understood they would have to be his most important “customers,” and any structure created around them would have to be of their own choosing.

Writing to his father in those early years, Jaffe admitted the obvious limitations of the style dictated by the Hall and its musicians. But he clearly understood the overriding purpose, too. “I don’t think we can ever get rich doing this,” he wrote his father, “but I think we can do a good thing.”

“I don’t think Allan heard the music as a thing apart from the musicians who made it,” a friend once told author William Carter. And it wasn’t long before Jaffe melded the Hall’s management with the music and the musicians, joining the corps of available musicians himself, making use of early training on the tuba that earned him a scholarship to a private boarding school during high school. Before long, Jaffe was playing tuba with the Hall’s primary touring band. As the music, the musicians, and identity of the Hall became fused in a single phenomenon, Jaffe cast himself as more of a caretaker than a manager, ensuring that the atmosphere at the Hall deliberately reminded listeners of the fundamental nature of the music.

There’s a kind of standing joke among New Orleans scholars that says when visitors regard Preservation Hall’s modest, weather-beaten façade—now worn to a silvery gray that gives up pastel undertones of soft rose and light emerald on overcast or rainy days—they often tell themselves, “This is where jazz was born.” To be fair, it’s not hard to understand how anyone might make that assumption. Jaffe intentionally maintained the Hall as a piece of living history, deliberately refusing to provide air-conditioning, rest rooms, or refreshments of any kind. Everything about the Hall, in fact, is designed to reinforce the intimate nature of the experience within.

From the very beginning, Jaffe simply opened the doors to the Hall’s adjoining carriageway, then collected admission while seated on a wooden stool with a straw basket in his lap. Once inside, visitors were left to find the music on their own, tentatively entering the performance room, standing or sitting until the band members arrive and the music began.

Announcements are usually limited to musician introductions. “When people come in, I don’t want it to be clear-cut on what you’re supposed to do,” he once explained. “You’ve got to come in and figure it out yourself; there are no big arrows and signs that say: this is what you do. Here’s someone who stood in line for 20 minutes, and he still comes out with that feeling that he discovered something himself. It’s exciting.”

Touring Creates a Sustainable Business Model

To support the Hall financially, Jaffe set out to accomplish what many believed to be impossible: booking musicians from the Hall on national, and even international, tours. This would insure financial solvency as long as there were bands to tour. But it took five years to book the first tour. “I spent whole days sometimes,” Jaffe told author Frederick Turner in the mid-1980s, “just sitting in the outer offices of booking agents in New York, trying to get in to talk to them. Nobody wanted to take a chance on us … [They] were all worried that the guys would die off before the concert dates. They’d say to me, ‘Look, we book a year in advance. How can you guarantee me a band by then?’”

What they didn’t know was that Jaffe had, by then, accumulated a list of as many as 200 musicians willing to work at Hall, many of whom could already be heard playing there in the course of a month’s scheduling. Eventually, the relationship between the running of the Hall and the participation of the musicians took on the dynamics of a family partnership. The musicians were the family elders, and the Jaffes became their protectors and sponsors. Growing up in that family, Ben Jaffe says it “felt like I had dozens of grandparents watching over me, answering my questions, reprimanding me, teaching me invaluable lessons about music and about life.”

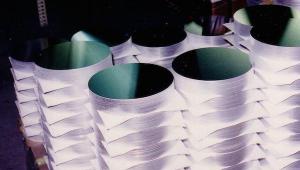

Eventually, the Preservation Hall “brand” became established: as many as three bands were touring the world at any given moment, often stopping annually to renew a fond acquaintance with a familiar audience; the homemade Preservation Hall LPs sold quietly in the Hall’s carriageway gave way to international releases on CBS’s Masterworks label, the only jazz band on the classical label; and the band personnel settled into a productive routine, with the Humphrey brothers, Percy on trumpet and Willie on clarinet, fronting the Hall’s premier touring ensemble. And the Jaffe family was thriving, their two sons, Russell and Benjamin, both in their teens.

But then tragedy struck—in December 1986, at the age of 51, Allan Jaffe was diagnosed with an untreatable form of skin cancer; he passed away in March 1987. Shortly before he died, he speculated about the Hall’s future. “Some of the musicians introduce my two sons to people as ‘This is going to be my boss,’” he told author William Carter. “But I think that assumes an awful lot. Parents like the idea of the children following in their footsteps. It gives a certain amount of assurance in their own life that what they did was worth copying. It also assumes the Hall is going to continue that long. As long as there are musicians playing traditional jazz, I’d certainly like to think that, but when I start to visualize it, it’s hard to visualize who is going to be playing there.”