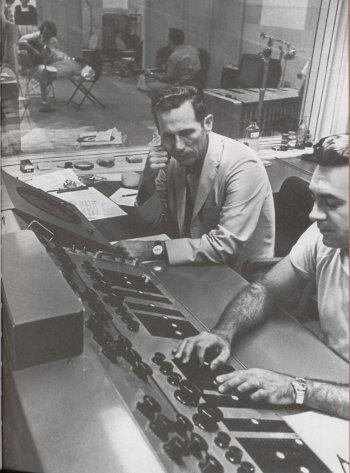

Recording Elvis and Roy With Legendary Studio Wiz Bill Porter

This is part of an interview I conducted with the great recording engineer Bill Porter back in 1987. I met up with Porter at Denver audio dealer Listen Up! We chatted and listened to some of his recordings. The remainder of the interview will be posted at a later date, along with listening session notes.

In part I of my interview with legendary Nashville engineer, Bill Porter, I wrote, “In one month of 1960, Porter-engineered recordings accounted for 15 of Billboard's Top 100 Singles.” That was a mistake. In fact, Porter had 15 charted singles in one week.

You could chalk it up to his having folks like Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, Chet Atkins and the Everly Brothers to record, but then you'd have to explain why, with Porter out of the picture, so many of their careers took a nose-dive. The fact is, the original pressings of many of those classic Porter recordings possess a natural, spacious, jump-out-at-you “live” feel that today's engineers don't seem capable of achieving.

Currently, Porter teaches courses in recording engineering and the history of rock and roll at the University of Colorado, Denver, where I spoke with him last December. A listening session conducted at Listen Up, a High End store in Denver, was published along with Part 1 of this interview.

MF: We touched upon this a little earlier, but how has the role of the engineer changed, vis-à-vis the producer?

BP: Well of course, when I first got into the business there were very few studios across the country that weren't owned by the major record companies. There weren't too many independent studios. The major labels were RCA, Columbia, Capitol, Decca, people like that, and they tried to lease them out to pick up some business to offset the cost of operating. A lot of people didn't like the corporate approach to sound, so that's why the smaller studios sprang up. All the hits I cut, I just drew a salary at RCA. I got overtime, but…

MF: Big deal.

BP: Yeah.Big deal. The Elvis sessions were always on Sunday and that was double time. I made a week's pay in one day.

MF: Why was it always on Sunday?

BP: His choice. Fewer people hanging around.

MF: Was there security there?

BP: Not really. There was security inside the building. They always tried to keep the session quiet, but they never could. There were always a few dozen people standing around about the time he was supposes to arrive.

MF: I would imagine so! Now, today, I imagine the producer calls the shots-even on a technical level-and the engineer just…

BP: Well, back then if you were an engineer you were looked to for technical reasons, you were not considered part of the creative process. Of course I didn't know any different when I went in there. I always wanted to ad-lib musically, so I did.

MF: At the time they were made, were your recordings better than the equipment being used to reproduce them? Are you hearing things today…

BP: Oh sure! Do you know what we had for a studio playback amplifier? You won't believe it. This little funky RCA thing with 6L6 output tubes-a maximum twelve watts out-that fed two baby A-7s (Altec-Lansing) sitting on the floor. Not the control room, that was a bit better, but that was the studio playback system. You're talking about stuff that cost a couple of hundred dollars, you know?

MF: So hearing your recordings on this state-of-the-art stuff must sound different.

BP: Yes. You know that bumping and thumping you hear on Elvis's “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” That's not evident on my systems. You don't hear that.

MF: So basically, what was put in the grooves was a lot better than what people were hearing in those days, and now it's coming out. Given the catalog of deficiencies in that early equipment, how did you manage to get such good sound out of it? People talk about early equipment having no dynamics, and a lot of tape hiss and rolled-off frequency response and this and that, and the other thing. Those old recordings sound better than most of what I hear today! How is that?

BP: Well, for one thing, I discovered that the tape machines were better than I thought they were. But I really worked extremely hard to keep the signal-to-noise ratio up. It was a constant struggle. Tube checks. I'd check my machines on a daily basis. It's maintenance. Preventive maintenance solves most of your problems. It's basics. Some people think basics are too dull. I don't.

MF: What was your reaction to the introduction of transistorized electronics?

BP: Oh man! I hated it!

MF: Were you forced to use it?

BP: Yeah! I was forced to use it. I remember RCA senta tape machine down-they were in the tape machine business. It was all solid state. Boy, it sounded like it was running through sand. And I refused to use it. I set it up, and ended up using it as a cue amplifier for head sets! (laughs).

MF: And you went back to using what you knew was better.

BP: Yup.

MF: With that experience in mind, what do you think so far of digital recording?

BP: My experience with digital-and it's slowing changing…the first time I heard it I said , “My, what a harsh, strident sound.” Everybody was saying “Well ain't that fantastic!”. I said, “What's fantastic?” “Look! There's no noise.” I said, “Well listen to the music! What does that sound like to you?” “Oh it sounds great!” “You don't hear that high end?” I said. “Huh? What high end?” “That grainy distortion?” “Oh yeah, I didn't hear that before.” “Well, listen!”

MF: We keep hearing that the poor old Westrex cutters used to master all of those old records (we played today) were vastly inferior to what's available today. Yet those old recordings sounded so good.

BP: Well I worked with those cutters quite a bit. Those cutters work on a feedback principle. And those old Westrex cutters had a resonant frequency that was in the audible range. You had to work to get it out. It was a matter of tweaking to a certain extent.

A lot of the old equipment had the potential for tweaking. Nowadays you don't have as many options. It's there, or it's not there. The old equipment had a personality you could doctor. I did a lot of that. Some of it wasn't exactly technically correct, but I listened to what I heard, not what I read on a scope. What I heard is what counted. People don't listen to a scope. You don't say, I like the music because the measurements are great.

MF: I'm afraid that is done.

BP: The ear is the final judge. Now if your going to use specifications-the ear can't decode that. I'm afraid what's going to happen is, you're pre-conditioned to what you learn as you grow up-what you hear-and if you don't keep some of the older stuff around as a standard, you're going to have no basis for comparison.

MF: I think that gets to the heart of the reason for conducting this interview.

BP: A whole generation of people grow up not having any comparisons, they won't know if it's good or bad. All they know is what everybody tells them.

MF: Well when the first generation of compact-disc players arrived and they sounded as bad as those early solid-state amps, when people wrote how great they sounded, those of us who really care about all of this tried to sound the alarm but were vilified for our efforts. Let me lighten up here. Have you got any good Elvis stories for us? I mean did you realize then just how special those moments with Elvis were?

BP: Nah! When you're doing three, four sessions a day, artists come in and out, some you know, some you don't, some are big artists, some aren't, you just do your job and go home. I knew who Elvis was, but he was just another client. I din't know if Elvis liked me initially or not, because I had a tendency to talk rather quickly and in a high-pitched voice, and when you push the talkback button under stress…

Anyway, when we recorded “It's Now Or Never,” Elvis had to do multiple takes because he kept missing the ending-it's a pretty high note. And ita was the middle of the night. I said after one take, “EP, I can splice that. We can just cut dthe ending. And he said “No, I want to do it all the way through, Bill. I want to do it all in one take.”

So we struggled with it. He finally got it, of course, you could tell…Presley sessions were kind of strange…all these hangers-onthat were his entourage. To a certain extent they were a lot of “yes” people. When he was doing a recording, they would be in the front room playing cards, or something, they could care less. Then, during playback time, they'd come back and ita was the biggest glad-hand slapping you ever saw. “Yeah, that's fantastic! That's great!”

See back then, and I don't know if it's because he didn't have enough clout or an RCA rule, or what. But back then tape copies just didn't go out the door. He didn't hear it again until it was actually released.

So we would do playbacks after the sessions sometimes maybe a couple of hours because he'd want to hear things over and over and over again. And on “It's Now Or Never,” he had me play it about twenty times.

MF: Who was the final arbiter in these decisions?

BP: Well Steve Sholes and myself, basically; Elvis didn't come in that much. Sometimes Elvis thought he did a bad job of something and Steve would talk him out of it. Steve Sholes had good ears and he was a good guy to work with. He died. Had a heart attack in Nashville about ten years ago. Great talent.Likeable fellow. He brought Chet and Elvis to RCA.

MF: How “sound conscious” was Elvis? Would he reject a take because he didn't like the way something sounded?

BP: Well, as far as all the recordings I did with him, he never said anything at all about the sound quality. Zero. Felton Jarvis, who was his producer during the later period, basically called the shots, so Elvis didn't butt in too much. Once in a while he'd ask for a remix or something; but all the time I was working with him, he never made any comments at all about the sound or the balance.

MF: Was he conscious of how his voice sounded?

BP: Oh yes. Definitely. He always was conscious of that.

MF: Did he ever tell you to put more of less reverb on it, or things like that?

BP: No. He never told me anything about that. The only time he was really concerned was when I was working on sound reinforcement [for live performances].

MF: Did you make suggestions for getting closer to the mike, or further away?

BP: Oh yeah. And he always said “Bill, I'll work the mike the way I want to. I don't want to be heard too much. Don't try to turn me up. I'm trying to do this intentionally…” I said “OK!”

MF: Was this done in a friendly tone or did he throw fits?

BP: He never threw fits about sound…well let me rephrase that. He got very upset if he couldn't hear everything on stage, and I think rightly so. That's how I got working with him again, as I told you. There were no monitors. When I got them up, he could hear. He never got as bad as Paul Anka, for example. Paul Anka, I think, is deaf. EP was not a typical dictatorial musician. Sometimes he would comment on the musician's part. He'd want to have him play something a little different, but he never criticized what the guy sounded like.

MF: He never brought in any recordings and said, “I like this sound, can we get that?”

BP: Nope. Never did.

MF: Did he ever express concern about how something would sound on the radio? Was he concerned about the commercial aspects of a recording?

BP: No. Not to me. Maybe later on. I know on his jukebox at his house were all the Orbison hits I'd recorded. I know he liked the sound of those. Sometimes I'd askhim, “What do you think?” He'd say “Fine.”

MF: There weren't headphones in those days-you just stood there and listened live, right?

BP: If you listen to some of those re-releases of “Reconsider Baby” and stuff like that that's out now-I think I have three or four on those packages-and you can hear him lean off the microphone and yell to the other guys.

MF: Who played on the Elvis sessions?

BP: Buddy Harmon on drums, Bob Moore on bass, Grady Martin and Hank Garland on guitar, and Boots Randolph on sax. D.J. Fontana on drums and Scotty Moore on guitar. That's the basic nucleus.

MF: How much of what we hear was pre-arranged before they got to the studio? Were there charts?

BP: No. A guy named Freddy Bienstock (Porter pronounced it “beanstalk” but I think my spelling is what he had in mind) who ran Hill and Range Publishing Company would come with a stack of demos on record with lead sheets. I'm talking about maybe a foot-and-a half high. I'm not exaggerating. We had a little record player for 78s and Freddy would've already culled some material, and he'd bring this big stack out and he'd go through it, five or six down and he'd pull it out and put it on for Elvis and say “Hey, listen to this.” Elvis would say “I don't like that.” So he'd pick another one.

MF: So at this stage, Elvis was the arbiter. Steve Sholes didn't say, “Now Elvis, wait a second.”

BP: Now wait! Everything was culled to a fine point. It was Elvis's choice, but he didn't have the initial picking. They led him to hear what they wanted him to hear. If he didn't like it, he'd say “No, I don't want to do it.” I found that the ones that imitated him on the demo, he liked them…Then they'd play the record over and over and over again and the musicians would learn the part-and it was all ad-lib-nothing was written down, not even chord sheets.

MF: This is all happening while the studio time is booked and the clock is running?

BP: Yup! We start at nine at night and go until seven or eight in the morning and we'd record anywhere from eight to fourteen songs.

MF: (incredulous) Eight to fourteen songs? Finished in one night?

BP: Yes sir, you heard me correctly.

MF: From the point of picking the songs out of the stack, learning the parts and doing the takes, you'd end up with eight to fourteen songs in one all-night session?

BP: Exactly.

MF: You couldn't do that anymore!

BP: Musicians make a difference. If they get their act together quickly, then it's up to the technical staff.

MF: So who was the arranger on all of these things?

BP: There was no arranger! A lot of times they'd copy the demo like it was. But mostly they'd just try stuff.

MF: It sounds like anarchy. I mean, who was producing these sessions?

BP: Nobody.

MF:Nobody?

BP: Not as far as I could tell. Well Steve Sholes produced, using the term loosely. But Freddy Bienstock was in charge of music selection. Sometimes Elvis would hear a lick and pick up a guitar and the musicians would follow him, but there was no one person in charge of every song.

MF: So one of the reasons why all this was so exciting, is because it was fresh. Totally fresh.

BP: Exactly The licks were original from the date-except when they copied the demos, which were darn good sometimes.

MF: Where do you suppose all those demos are today?

BP: Boy, I have no idea.

MF: Those would be absolutely fascinating to hear…When you began to record Elvis he had had a whole recorded history before you got to him. Didn't anybody say to you, “Well Bill, here are Elvis's old recordings and we want to continue the sound where we left off.”

BP: Nobody said boo. I wasn't told what to do, or how to do it.

MF: And you didn't say to yourself, “Well, Bill, I'd better go back and”…

BP: I didn't have time. I'm serious. It was just another session. I was hung up on a quality kick, trying to get some depth into those recordings and it was just another client to do the same darn thing with. You know Elvis had a lot of hits before I came along…but after we left…

end of Part 1

- Log in or register to post comments