Roxy Music The Complete Studio Albums : There’s a New Sensation! (Updated 5/11/15)

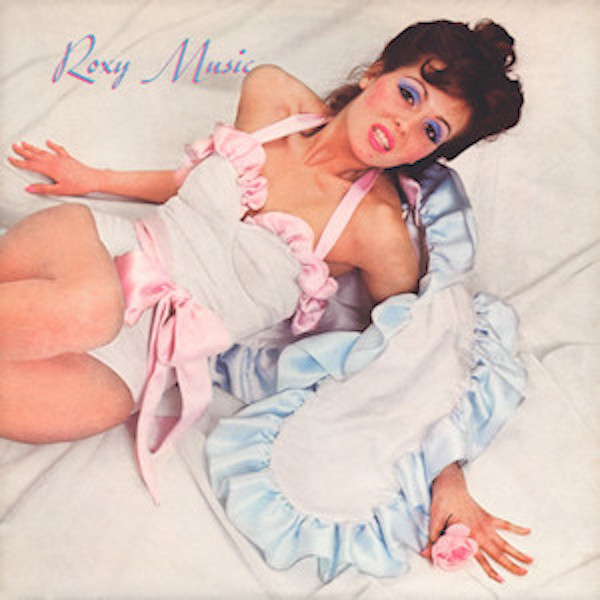

A pin-up cover girl in 1972? Slicked back greaser hair, and while you’re at it an album jacket clothes, make-up and hair credit? Maybe you weren’t around for it in 1972 but back then this—not long hair, sandals, checked flannel shirts and bell-bottom jeans— was outrageous. Those were so yesterday-hippie.

These glam-rockers were trying to move beyond 60’s culture but to do so they had to look both backwards to the 1950s for the roots of both the music and the culture, and forward to wherever that might lead.

In the era of women’s lib, the first Roxy Music album cover was more than provocative, it was “sexist” and a throwback to a bygone era—one that the counterculture had abandoned and left for dead.

But Bryan Ferry (who’d been fired from a ceramic teaching job at a swank girl’s school for throwing ‘record parties’) knew what he was doing.

Though Ferry’s background was working class-modest he clearly was fixated on the trappings of wealth and privilege and not at all shy about going there both visually and musically, despite the hippie era’s egalitarianism.

While the band was way over the top for culturally conservative America (and by that I mean the “hippie enforcers”, not the Nixonians), the eponymously titled first album Roxy Music (ILPS 9200) got to No.10 on the UK album charts. “Virginia Plain” recorded after the album’s release reached #4 on the U.K. singles charts. The song was reissued in 1977 b/w “Pyjamarama” to promote a “greatest hits” package and it again charted, reaching No. 11.

Ferry formed Roxy Music with bassist Graham Simpson whose picture appears on the original U.K. Island pressing but not on the American Reprise original. By the time of the Reprise release Simpson had left the band, replaced by Rik Kenton whose photo appears on Reprise MS 2114. More wedded to the California “alternative culture” than what was happening in England, Reprise had little immediate success breaking a band it little understood.

Saxophonist Andy Mackay responded to an advertisement and was hired, bringing with him Brian Eno, who owned a few Revox A77s but was not a musician. He was hired as a technician but soon joined the band. When the original drummer departed Paul Thompson responded to another advertisement and was quickly onboard. Phil Manzanera was first hired as a roadie after losing the guitar job to former The Nice guitarist David O’List, who quit after fighting with Thompson at a management audition. Manzanera was quickly hired after demonstrating that he knew and could proficiently play the repertoire.

Roxy Music

On the British release’s annotation, Simon Puxley writes “what’s the date again? (it’s so dark in here) 1962? or 20 years on?”. Correct he was! The album, produced by King Crimson lyricist Peter Sinfield, who met Ferry at the group’s vocalist auditions, opens with “Re-make/Re-model”, a saxophone-fueled rave-up that after beginning with a restaurant crowd sound effect, puts one foot in the 1950s, and the other in 60’s era Velvet Underground, with stopovers for “Day Tripper” and “Ride of the Valkyries”. Everyone gets a chance to add a short solo and the song ends with Thompson shutting down the engine and Eno adding wiggly synth squiggles, leaving 1972 listeners pretty much unhinged but wanting more.

“Ladytron” opens with atmospheric synth and oboe, hits the castanets and then takes a “Telstar” break before heading into a guitar and synth driven free flight that, for those willing to go there, leaves in the dust hippie folk music.

“If There Is Something” begins as a simple vamp but turns into a romantic plea from Ferry that expresses male desperation most often heard in soul music (minus the potato growing offer). Andy Mackay’s sax and oboe work light the song on fire. The song’s abrupt final section, filled with nostalgia and regret (“the trees were taller when you were young”) makes clear that this is a band with a musically and lyrically expansive agenda, though the side-ending mawkish Humphrey Bogart tribute “2 H. B.” is one Ferry might wish to forget.

Ferry takes a back seat on most of side two beginning with “The Bob (Medley)”, an art-rock/avant-garde jam session mostly gone wrong, followed by the exquisite trifle “Chance Meeting”, in which a sad young man handles poorly running into an ex, with self-loathing and pity on the plate.

“Would You Believe” is a Chuck Berry meets Jerry Lee Lewis throw away rescued by great playing by all. Just when you think the album is going to peter out and grind to a halt comes “Sea Breezes”. As on the rest of side two, Ferry’s voice is mixed way back, but this song of love and regret, anchored again by Mackay’s oboe and Ferry’s keyboards, plus Manzanera’s dissonant guitar riffs and Thompson’s off-kilter marching orders spotlights an old school romantic songwriter who wears his heart on his sleeve backed by a group of instrumentalists that could deliver the sparks needed to fulfill the songs’ strong demands. The alcohol-tinged “Bitters End” 50’s style denouement, ends with a smattering of the opening sound effects and ends with Ferry’s regrets:

So will someone please find me

Give now the host his claret cup

And watch Madeira's farewell drink

Note his reaction acid sharp

Should make the cognoscenti think

The Sound

The first Roxy Music album on the original U.K. pressing is a wildly uneven-sounding album: part muffled, part pretty good. The American Reprise is lackluster throughout.

However, the mix is very well accomplished so despite the generally muffled drums and lackluster top end, there’s plenty of midband detail and even some transparent elements worth digging out of the grooves—the breaks in “Ladytron” for instance.

Why mastering engineer Miles Showell, who cut ½ speed at Abbey Road ended up working from 96/24 files is unclear. Was it a money issue? It’s generally less expensive cutting from files. Or, were the tapes in fragile condition? We don’t know. It’s also unclear if Mr. Showell thinks a 96/24 file is transparent to the analog source.

A comparison between a few original “pink label” Island originals and the reissue indicate that the goal was not to duplicate the original but rather to somewhat “modernize” on the reissue.

Whether the reissue’s more prominent bottom end is what’s on the tape and was cut on the original or the result of an EQ boost is something only the mastering engineer can answer. I found the bottom end on some tracks excessive. I said to myself more than once “Is Miles a bass player?” though it was the thumpy kick drum that more often intruded.

However, the overall transparency is improved and the top end, while more open, is not excessively bright. Dynamics are greater too. However, images are “thicker”, less finely drawn and somewhat two-dimensional compared to the original. Depth is somewhat foreshortened as well.

The cut is definitely hotter and sounds louder than the original. You can listen below to one-minute excerpt from an original and from the reissue. The files were transferred at 96/24 and yes, of course, one is a digital transfer of an analog source while the other takes a zig-zag course of analog to digital to analog to digital (etc.). Still I think you can clearly hear what Showell has done and decide for yourself if you like it or not. You’ll know which is which! (Both files were "normalized" to -.1dB max level using AudioLeak).

For Your Pleasure

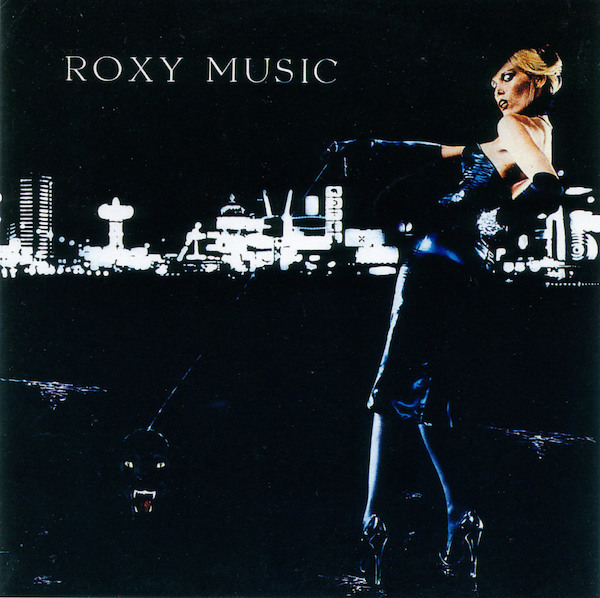

Pin-up girl cover past, what outrage to perpetrate next? Ferry chose kings of tackiness circa 1973: Las Vegas, a bloated Cadillac limousine with a grinning Ferry as chauffeur to a stiletto-heeled blond (Amanda Lear, who was Ferry’s squeeze at the time) tethered to a leashed black panther.

You have to understand how positively offensive to the prevailing esthetic was absolutely everything in that graphic. Neil Young at around the same time released Time Fades Away. The Byrds, their not particularly well-received Byrds reunion album on Asylum. It was also the time for Dark Side of the Moon. The most outrageous album of that year was clearly this and Bowie’s Aladdin Sane, which, unlike For Your Pleasure did not include a song about an inflatable doll.

This album opens with the audacious “Do the Strand”—an invitation to dance in a post-dance craze era of no Twist, no Watusi, no Mashed Potatoes, no Madison and certainly not a time when anyone other than Roxy Music was suggesting a dance as the “solution to teen-aged revolution”!

No actual dance moves were associated with “The Strand”, which like “Virginia Plain” was a cigarette reference. Though there was no actual dance, the suggestion was that hipness would follow doing it. Lolita did it. Ferry’s crooning style acquires greater authority and muscularity here and throughout the album.

“Beauty Queen”’s “Valerie” refers to Valerie Leon a former beauty queen of a girlfriend. The hopelessly romantic Ferry again sincerely wears his heart on his sleeve. The arrangement follows the early Roxy pattern of a instrumental break that shifts into guitar-driven Velvet Underground overdrive that sounds as if it inspired the sound Morrissey and Johnny Marr created for The Smiths.

“Strictly Confidential” is a song of desperation—a hyper-dramatic throwback to the debut album’s second side while “Editions of You” was the album’s second full blown rave up tune that gave everyone in the group a chance to cut loose. Memorable line “Too much cheesecake too soon”.

The side ends with “In Every Dream Home a Heartache”, the creepy inflatable doll song in which the doll is a metaphor for alienation. If Ferry wasn’t thinking of nighttime in the L.A. Hills when he wrote it, he should have been!

Side two includes but three songs: the austere, insistently monotonous, nightmarish “The Bogus Man”, which though difficult to sit through or to comprehend in 1973 makes all too much sense in 2015. 1973’s popular music scene had nothing whatsoever to do with “The Bogus Man”! Back then, I remember either skipping it or waiting impatiently for it to end. “Grey Lagoons” has some memorable lines like “Satin teardrops on velvet lights/Morning sickness on Friday nights/Heaven knows what others I might bring/To you” and equally memorable Phil Manzanera licks.

The album ends with the title tune, which was Eno’s final Roxy Music statement. He made the most of it with off an off-kilter, almost nauseating ending featuring spinning, looped synthesizers that morph into a draining funnel of sound and vocal echoes from the end of the first Roxy Music album.

After the U.K. chart success of the debut album, Island gave the group a bigger budget that allowed them to record at AIR Studio and to take more studio time to produce this album. That’s obvious in a far superior sonics, the vastly improved production and the album’s overall cohesiveness.

The bass and drum sound in particular are far superior and the overall sonic picture more spacious and better extended on both top and bottom, with greater depth, three-dimensionality and dynamics.

While the reissue taken on its own terms sounds very good, when you go back to a clean U.K. Island original you hear that the reissue loses instrumental “elasticity”, particularly the drums and bass, which, while arguably better extended and clarified, sound cardboard-like compared to the original. Depth is foreshortened and image edge definition coarsened.

The reissue sounds “clean” and very well organized, and in no way does it sound bright and/or hard but it lacks subtlety and suppleness compared to an original U.K. pressing. Transients are softened and vocals also take a reality and transparency hit.

There are certain sonic characteristics shared by the first two albums that had me thinking I was more hearing the A/D, D/A converter’s character than that of the master tape.

Still, without comparing to an original, the reissue sounds good on its own terms though I’m reminded of what I heard comparing an original UK pressing of John Lennon’s first solo album with the digitally remastered Mobile Fidelity reissue.

Here’s a video I found on YouTube showing Roxy Music performing “Editions of You” on a German television show back in 1973:

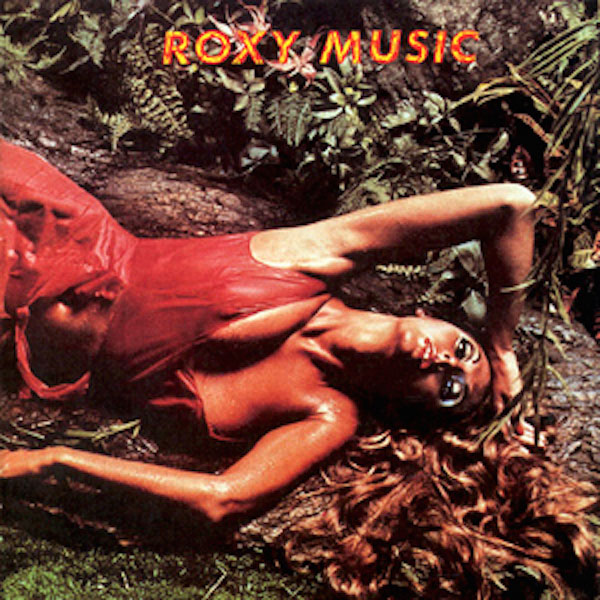

Stranded

Stranded, released in November of 1973 featured yet another pin up cover, this time a genuine Playboy Bunny named Marilyn Cole who didn't know the band Roxy Music. She took the cover gig but apparently was surprised when the photographer Karl Stoecker, began ripping up the dress.

Though Eno had left Roxy Music, “Street Life” begins the album with some Eno-like signal processing, perhaps contributed by new member, the multi-instrumental Eddie Jobson, (or it could be Andy Mackay’s), followed by an uncharacteristically ebullient, optimistic and adventurous Bryan Ferry lyric. His only complaint: too many phone calls, though he’s not sold on a college education because “the good life’s never won by degree”.

Then on “Just Like You” he’s back as the star-crossed lover, lost before he’s found, vowing to “never again, no, will I give up my heart”, but finally admitting he’s got no choice, he’s “fallen head over heels, over you”—whoever that might be.

For the first time, Phil Manzanera contributes a tune, with Ferry getting co-writing credits. “Amazona” is no throwaway or sop to a frustrated sideman. Instead, it’s among the album’s high-energy stand-outs, with a flashy rhythmic line driven by an even flashier guitar-shriek. The far-flung lyrics about escape and hope are fanciful and visually evocative.

Ferry’s “Psalm” has to be among, if not the most heartfelt proselytizing song ever written—and one that even a committed agnostic or atheist might find intriguing, propelled by strong studio atmospherics and a thunderous kick drum that sounds like the earth's heart beating.

Side two opens with another hopelessly-romantic Ferry end of affair onto the next one, ending with “Call the tune, will you swoon?/As I croon, your serenade”?

Mackay/Ferry team up again for Roxy’s most melodramatic broken-heart songs, “A Song For Europe”, where the ache is set in Paris but travels to Italy, with lines like:

Now, only sorrow

No tomorrow

There's no today for us

Nothing is there

For us to share

But yesterday

There’s a break where Mackay takes an arching saxophone solo that perfectly heaps on the weepy heartache after which Ferry sings/speaks undying love in Latin and French. It tears down the house performed live.

In “Mother of Pearl” Ferry explores his quixotic quest-obsession versus life’s search for meaning. The song begins chaotically setting the picture: “Turn the lights down, way down low/Turn up the music/ Hi as fi can go….”.

Then the song takes a contemplative turn lyrically and musically with yet another song with an insistent kick drum anchor. Ferry sings “With every goddess a let down/Every idol a bring down/But the search for perfection/Your own predilection......”Career girl cover/Exposed and another/Slips right into-view”.

The song ends with an acapella chant then seamlessly segues into the “Sunset” finale, soothed by Chris Laurence’s double bass. How many times did that album's second side accompany my California sunsets? Can’t count.

Roxy was big in the U.K. from the beginning but pretty much ignored in America. Because Stranded was an album of straightforward songs and didn’t include any extended “experimental” pieces, it was easier for less musically adventurous Americans to grasp and it became the first to make some sales inroads, though it barely made a blip at 186 on the Billboard Charts. It hit No. 1 in the U.K.

Produced by Chris Thomas at AIR Studios, Stranded was the most sonically coherent and atmospheric album yet. You could sink in and be drawn into Ferry and company’s stylish and grand world. Songs like “Song for Europe” and “Sunset” took listeners to a far different place than most of the era’s rock music. Only Procol Harum’s Grand Hotel, also issued in 1973 moved in similar circles.

Reading the lyrics to this album and the preceding two for that matter makes clear that Bryan Ferry’s writing was seriously undervalued, lurking in the shadows of his unique vibrato-rich, throw-back crooning.

The original U.K. Island release was clearly compressed dynamically and that appears to have been done in the mix because the reissue is equally so. The original’s treble was somewhat lifted and the bass a bit rolled. This reissue produces a better overall tonal balance while sacrificing some of the original’s “atmospherics”, spaciousness and overall smoothness.

For instance the sax solo on “A Song For Europe”, physically prominent and forward in three dimensions on the original, blends into the flatter wash and is less “reedy” sounding.The same with the cymbal splashes that don’t have the same generous decay, but that could be the result of the tape having aged over forty plus years! However, of the first three albums Stranded is mastering engineer Showell’s best work. If these are ever issued individually, it’s worth picking up.

Please read the second part of the box set review.