A Week In The Past---David Jones In New Orleans 1961

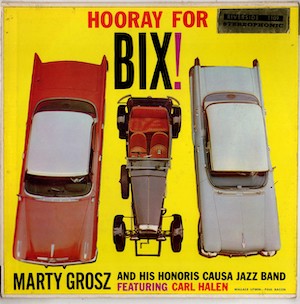

Jones began his career in the early 1950’s in Yellow Springs, Ohio, recording traditional jazz for the Empirical label, which he probably owned. By December 1953, when he recorded the now forgotten Gene Mayl’s Dixieland Rhythm Kings in an empty hall, using an Ampex 350 recorder and two mics which he placed in front of the band, with no close miking, he had found the minimalist style that he would use and refine for the rest of his career. These mono recordings have a wonderful sense of space and air with great front-to-back imaging; but they lack the “David Jones magic.” The missing element was stereo. In December 1957, in Yellow Springs, in the same month that the first stereo records were introduced for sale in New York City, Jones demonstrated his prescient understanding and mastery of the new format when he recorded Hooray For Bix (Beiderbecke) by Marty Grosz and His Honoris Causa Jazz Band (Riverside RLP 1109).

This superb recording is one of the greatest examples of early stereo. The sound is warm and ultra-detailed with a large, but not unrealistic dynamic range. Stereo separation is wide but without the “hole in the middle,” common in early two channel days and imaging is 3-D visible. Hooray For Bix makes obvious that Jones, even at this early date, understood that the benefit of stereo was not that it could make sounds seem to move, but that it could produce more separation of the instruments and deliver room sound, making possible pinpoint imaging and thus, greater naturalism and realism.

Sometime in 1958, Jones moved to New York and approached Riverside Records, probably to seek employment. While a job was not offered, Bill Grauer, one of the two owners, was impressed by Jones’ work in Yellow Springs and purchased for issue on Riverside some of his Empirical recordings plus the unissued, Hooray For Bix. Soon, Jones did find employment; as chief engineer for Elektra Records. The label’s late 60s rock heyday was nearly a decade in the future and commercial folk was paying the bills. It’s difficult to imagine that Jones could muster much enthusiasm for Ski Songs, More Airforce Songs, Tell It To The Marines and a series of risqué folk song LPs, but he recorded very well even this pallid music. It seems likely that Jones convinced Jac Holzman, Elektra’s owner, to allow him to record some music that he actually liked. The result was Cuadro Flamenco (Elektra EKL 259-X), a bona fide audio masterpiece. While the music is not the type of deep, soul piercing Flamenco that Jones was later to record, it is very good and the audio is spectacular as dancers stomp across the soundstage, castanets clicking above their heads. Seemingly, the occasional personal pride project was not enough, and the surfeit of comedy corn folk was too much; and in 1960 Jones quit Elektra and began his freelance recording career.

Probably, at about the same time, Bill Grauer made the decision that Riverside would fund the “Living Legends” project. Recording Black traditional jazz in 1961 was rare and when done was the province of one-man collector/fan operations, not successful independent labels that specialized in modern jazz, like Riverside. The ambition of the project was unprecedented for a commercial record company. Recording Black American music in a documentary fashion was more akin to the work the Lomaxes had done for the Library of Congress, than the normal commercial imperatives of the record business. The scope of the project, eventually ten and a half LPs, documenting one type of music, in one city, in one week had never been attempted before. Grauer was also determined to make better sounding and more authentic recordings of New Orleans jazz than had ever been done. He had heard many of the greats live and knew that the recordings available weakly reproduced the power and polyphonic complexity of a New Orleans style band.

Sending an experienced New York engineer to record in a top New Orleans studio was his original plan. However, New Orleans was a segregated city; still tightly in Jim Crow’s grip, and all of the best studios refused to record black musicians. Rather than abandon the project, Grauer made a decision that was daring and potentially disastrous. He hired Jones to make the recordings live and on location, gambling that releasable recordings could be made under conditions that any other record company would have considered archaic and impossible. Clearly, Grauer had to have been extremely impressed by the recordings that Jones had sold him two years earlier, to take a chance on a little-known freelance engineer with such idiosyncratic recording methods.

On January 20, 1961, the day of John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, Jones and Chris Albertson, a Riverside staff producer, headed south to New Orleans in a van crammed with recording equipment. “The Sixties” had begun. The nation was heading toward a “New Frontier” while Jones and Albertson were embarking on a journey into the past of American music. A past that had been left behind in New Orleans when Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Sidney Bechet and so many others had brought jazz to the North and to the world, paving the way to the Swing Era and all that was to come after. Many of their peers, however, had remained behind, continuing to play New Orleans traditional jazz, untouched by the many musical developments their music had spawned. The musicians Jones and Albertson were seeking were as yet unknown to them. Grauer had not instructed them to record anyone in particular. They did know that they were not seeking Al Hirt or Pete Fountain or any of the “tourist dixieland” acts that were filling clubs in the French Quarter. That would have been a job for record business pros, requiring only clever negotiation and a check book. Instead they were searching for a “sound” that Grauer trusted them to recognize when they heard it. It was a sound that could not be heard elsewhere. Maybe they would have said it was the sound of “soul” or maybe, they would have said “authenticity”, but they would have known they were the same.

They arrived in New Orleans on January 22, began auditioning bands the next day and started recording on January 24. Chris Albertson later wrote that there remained “only twenty-seven living musicians still able to play in the true New Orleans tradition.” One could call the musicians Jones and Albertson chose to record not “folk musicians” but “for the folk musicians.” They were all beyond middle age, the youngest 50, the oldest 73, semi-pros with musical roots in the 20s, who played social music for older people in the black community at bars, parties, dances and parades. Some of the gigs were rough, in places with names like “The Pigpen” and others were at family barbecues in the parks, but all were playing for “our folks.” These musicians had never played on Bourbon Street and wouldn’t have been even allowed in the clubs there. Jones and Albertson arrived just before culture and society in New Orleans began to change and the music with it. Ten years later, partly because of these recordings, many of these musicians would be playing for tourists and doing concerts in Europe and Japan. While the financial reward and respect accorded the musicians was just and deserved, the music wasn’t the same as it was in 1961 when they played only for the “folks” back home.

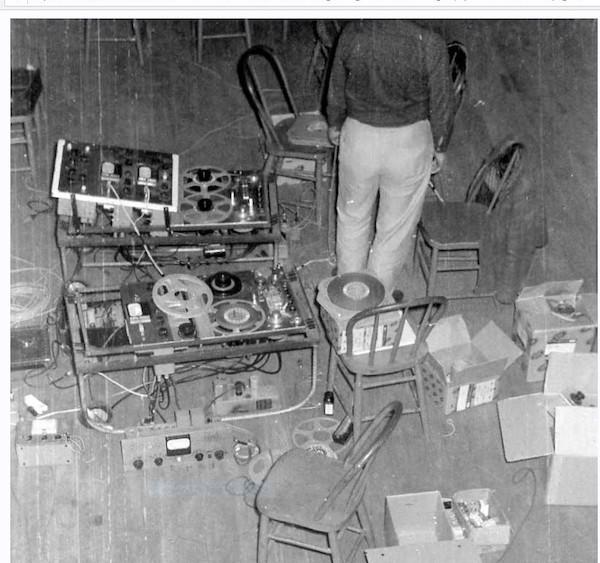

The recordings took place in Societe des Jeunes Amis Hall which had been built in the nineteenth century and belonged to a Black Creole fraternal organization. It was a small wood frame building, certainly not an auditorium, in a residential neighborhood and was used for parties, meetings and, in 1961, infrequent dances. Jones certainly chose it from other possible venues, apparently including a small studio, and it’s easy to hear why. The hall’s sound is dry, airy, warm and woody, yet tight and focused due to the comparatively small space and twelve to fifteen-foot ceiling. Not surprisingly, it’s a very similar sound to that of his Empirical recordings. In Jones’ own words, “the hall was all I could ask for.” The musicians played on a small, low stage at one end with a wall behind them. Jones set up his equipment nearby on the floor—two Ampex 350-2 two track recorders, an Ampex MX-35 mixer, Sony condenser mics, probably C37A’s and, for monitoring, two AR-3 speakers and a pair of Beyer headphones.

The Ampex 350-2s were state of the art, studio equipment and not designed to be portable but Jones had them mounted on wheeled racks. Jones later summed up his recording philosophy and the technique he would use for the sessions, “The choice was between the advantages and disadvantages of a large hall or a small studio. I could never see crowding the band into such small quarters that the artificial aid of an echo chamber was necessary, but soloists could be recorded with greater presence. I always preferred the natural sound of a good hall, but improper balance could easily cause a blurred, muddy effect. Better microphones plus the benefit of stereo, make it a great deal safer now to record in a hall. I was able to give Jim Robinson’s trombone all the presence it needed, without masking any of the other instruments. I tried for a combination of the old traditional sound and the closer miking given modern groups.”

In Societe de Jeunes Amis Hall Jones succeeded in finding the perfect microphone placements for the hall and the musicians and the balance he sought between close miking and the more distant sound of his Yellow Springs recordings. With the exception of the trio recordings and a few full band tracks with vocals, it can be seen from the session photos that Jones used three mics placed three to four feet in front of the musicians; one on the left between the trumpet and the trombone, one in front of the quieter clarinet and a third on the right in front of the banjo or bass but overhead or closer than the other mics. Contrary to common practice, he did not separately mike the drums, but allowed them to be picked up by the other mics, resulting in a natural, “in the room” sound without the exaggerated dynamics and cymbal brightness of close miking. Jones’ minimal, no close miking technique recorded the music as truthfully and as honestly as possible. Appreciating his recordings requires an acceptance of the imperfections inevitable when humans play music. Momentary “I got excited and played too loud” balance flaws and the inevitable “clinker” notes are heard unaltered and unfixed “in the mix.” Jones’ recordings in New Orleans reproduce the sound of the music with amazing fidelity but also its truth and humanity.

Jones and Albertson recorded ten and a half albums during their week of recording at Societe des Jeunes Amis Hall. The reasons why they are the greatest recordings of Black traditional jazz in the LP era are many. Because Jones and Albertson were fans, they understood the music and chose to record the best and most compatible musicians and allowed them to record the best parts of their repertoire, instead of demanding gimmicky pop and novelty tunes that might increase sales. The musicians were comfortable playing in the hall in familiar and relaxed surroundings rather than in a recording studio with time constraints. Finally, the importance should not be overlooked, of the fact that in the hall, they could hear themselves, the other players and, most importantly, the collective band, so that they could play together and balance themselves to sound the way they knew a New Orleans band should sound rather than having the studio engineer create a generic “good balance.”