Masters of the Art of Mastering Part 1

Editor's note (please read!).

This story was written in the late 1980's. I don't remember the exact date. At the time, Greg Calbi and Ted Jensen were working for Sterling Sound. Between then and today (2005), Calbi left Sterling and went to work for competitor Masterdisk for a few years. He later returned to the new Sterling Sound (www.sterling-sound.com), a sprawling complex on Manhattan's west side near the "meat packing district," where Ted Jensen and George Marino also work as part of one of the most distinguished teams of mastering engineers anywhere in the world.

So much has changed since this piece was written. Vinyl has made a comeback, digital has improved, and more people are willing to go on record extolling the superiority of analog and vinyl. I'm not sure if these two guys will go on record on it, but perhaps we'll hear from them and if so, we'll let you know.

Please keep in mind the dated nature of so much of what you're about to read. However, despite being "ancient history," I think this story remains a good read and I hope you agree.-MF

I love old Saabs. I have two model 96es- if you went to college in the Northeast, one of your professors probably drove one. Chances are it sported a "McGovern For President" sticker on the bumper. In fact, if only Saab 96 owners voted for President in 1972, McGovern would have won.

What does any of this have to do with disk mastering? Well, about a year ago, a guy pulled up next to me in a 1972 96 and asked me who did my mechanical work. He'd recently brought the car up to New York from North Carolina and hadn't been able to find anyone who knew anything about Saab 96es. I told him I was one of three Jews outside of Tel Aviv who did their own mechanical work. He asked me if I'd help him with his. Being a "Saab person" I said sure, and gave him my phone number.

What does any of this have to do with disk mastering? A few months later he called. He'd left the car in a friend's garage in Montclair New Jersey for a few months and now he couldn't get it in gear. Would I drive down and take a look? His friend wanted the garage back.

After determining that the clutch was frozen to the flywheel and couldn't be freed without removing the engine, the now distraught Saabophile summoned the owner of the house so I could personally give him the bad news.

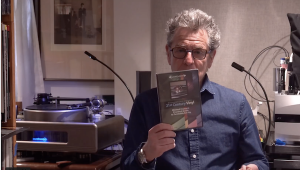

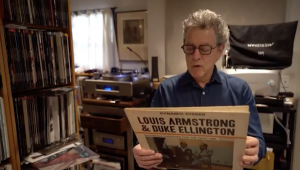

But first an introduction: "Michael Fremer, meet Greg Calbi." "Greg Calbi the disk masterer? I offered a greasy hand to the man who mastered Paul Simon's Graceland and Hearts and Bones, Arthur Delmoni's Songs My Mother Taught Me, Talking Head's Remain in Light, Dylan's Biograph box and hundreds of other albums over a fifteen year career.

After a delay of a few months (during which time I did a clutch job and got the Saab out of his garage), Calbi visited my apartment for a listening session. At the time, I had a VPI TNT/ET II arm combo, an Audio Research SP-11 Mk 2 on loan, a PS 200CX amp and a pair of Eminent Technology IV speakers and Kinergetics subwoofers under review, so when the opening drum "thwack" on Graceland hit, Calbi's jaw locked opened . By the end of the first cut he admitted that he had no idea so much information could be extracted from those grooves.

We spent a pleasant evening auditioning test pressings, reference lacquers, comparing LPs with CDs and just plain listening to music for pleasure. Calbi was particularly interested in hearing records he'd mastered over the years, on a system that let him know in no uncertain terms what he'd done. Mostly he was pleased. Occasionally he shook his head. We left the formal interview to sometime in the future at Sterling's facilities in midtown Manhattan.

I arrived at Sterling a few months later, on a day that will live in audio infamy for me. I spent almost three hours talking with Calbi, who studied journalism at the University of Massachussetts and with Ted Jensen, another disc mastering engineer at Sterling, who began working with Mark Levinson (the person) at the tender age of sixteen when MLAS was in its infancy. Unfortunately, my heretofore reliable Panasonic microcassette recorder decided not to exhibit its usually magnetic personality that night and it didn't take down a word of our conversation. Not too embarassing! I imagined Calbi thinking to himself: "Maybe this guy should stick with carburetors." Fortunately, I had formulated my questions in advance and I remembered the answers, if not the exact words.

Over the fifteen years Greg Calbi has been mastering disks, profound changes have taken place in the recording industry: the solid-state takeover, Dolby noise reduction, the ascent of the pre-recorded cassette, digital recording, compact disks, and Direct Metal Mastering among them.

But the technical revolution pales next to the esthetic one. The recording art, once defined as an attempt to faithfully capture a musical performance, has itself become the performance. Whereas in the Fifties and Sixties engineers may have employed "tricks" to achieve a natural sound, their basic goal was to get out of the way. Today's engineers paint more abstract sonic pictures, and they do so with very visible brush strokes. Anything goes in creating a unique "sound", even when recording acoustic music and vocals.

So today, the task of translating a master tape into a consumer-ready product has grown arbitrary, complicated and full of conflicting options. The master tape- once considered a finished product is now subject to considerable tampering in the mastering process.

Thus, mastering, once a glamourless, relatively unsupervised mechanical link in the recording chain has become a controversial hot spot. If there was an art to disk mastering in the early days of high fidelity and stereo, it was in overcoming the deficiencies of the old cutting lathes to get a good sounding record.

If you want to hear the transparently natural sounding mastering genius of a legend like the late George Piros you don't only have Mercury "Living Presence" classical LPs to listen to. George cut many pop records for Atlantic during the sixties and seventies.

Today the art is in giving the producer, or whoever is supervising the mastering session, what they want to hear- and that could be anything.

Calbi and Jensen say mastering sessions today are attended by everyone from producers and record label executives to the artists, and the artists' girlfriends and boyfriends, whose opinions often carry much weight. As in retail sales, ultimately, the customer is always right, no matter how wrong. To be a successful mastering engineer today, one must be a proficient tongue biter (your own of course).

Once, Calbi recalled, he'd done what he considered an excellent full-bodied cut of a new band's master tape. He proudly gave a reference lacquer to the band to take home for a listen. They came back in the morning insisting that Calbi redo it to sound more like Sting's latest album. They wanted thin and bright, so Calbi had to give it to them, even though his name was listed on the credits.

Frequently, an artist or producer will get a recording mastered at more than one studio and then choose the better sounding of the two. Better sounding on what system is of course the problem. Calbi remembers on Graceland, engineer Roy Halee approved a flat transfer reference lacquer even though it sounded a bit muddy and bass heavy in the studio. Halee told Calbi it sounded great at home on his Infinity RS-IBs.

Is it any wonder Graceland has been an audiophile favorite at C.E.S.? Interestingly, Halee has had second thoughts, going so far as to tell Calbi that in the event of a recut, he should filter the very low bass. I did my best to dissuade him from doing so!

At the other extreme is the fairly famous story about George Szell who insisted on hearing reference acetates after recording sessions with the Cleveland Symphony. To Szell's ears, the results were almost always dull. He demanded and almost always got the sound brightened up. After years of this, it was discovered that Szell's speakers (AR-3a's, I think) were tucked away under his living room couch!

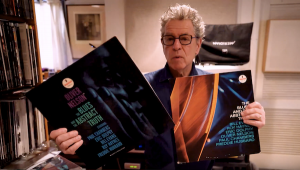

As on the listening side of the audio fence, the reference system used to master a recording is critical. In Ted Jensen's room, which was generously treated with Tube Traps™ and the like, I found a pair of KEF 105 IIs being driven by Krell KMA 200s fitted with Dan D'Agostino's reference "front end", connected by Monster Cable "Powerline II".

Jensen's analogue board is a custom transformerless Neve. The main analogue source is a Studer A-80 30 IPS 1/2 inch deck, whose electronics have been bypassed in favor of the Cello Audio Suite. Jensen said Studer

had really skimped on the electronics, filling the boards with chips and mediocre components, and that when he substituted the Cello, the sonic differences were "frightening". Equalization is accomplished through a Danish "Tube-Tech" unit. For disk playback Jensen has a Technics SP-15 fitted with an SME- II arm and a Shure V-15 Type V.

In the digital domain, Sterling has invested a half million dollars in two of the compact new Neve DTC boards which move between Calbi, Jensen and George Marino as needed. VCRs and PCM processors are on hand as well as Sony's 1630 for the final digital master.

Calbi's room is not quite so sumptuously outfitted for playback, although, of course the mastering equipment is on a par with Jensen's. The board is an older Telefunken which Calbi says is considerably more "transparent" than many newer designs. He's got a pair of large old Canton bookshelf speakers and some equally undistinguished electronics. Jensen and Calbi find it instructive to monitor their work on each other's playback equipment.

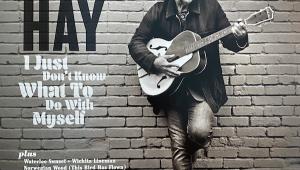

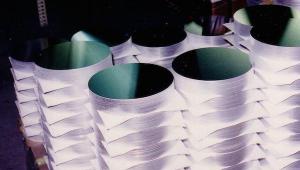

What are their feelings on DMM cuts (Direct Metal Master) vs. lacquer? Sterling offers both at their facility. Calbi and Jensen are both enthusiasts of DMM, but believe lacquer cuts have the potential to outperform DMM. Unfortunately today they rarely do. Even by company, lacquer quality varies widely and with the lacquer making (and using) population thinning out, only a few sources remain.

Both Calbi and Jensen insist that the lacquer quality problem has nothing to do with the declining use of lacquer based paints in the automobile industry, as some audiophiles believe. Quality lacquer is just difficult to produce and since LPs no longer dominate the market, its production is becoming a lost art.

Lacquer is also tricky to handle. It has a relatively short "shelf life", both before and after it’s cut. Calbi feels the original lacquer sounds better than the final record. Jensen disagrees, saying that if the plating and pressing are accomplished carefully, the final record should sound better, despite being a few generations down. Jensen feels that the soft lacquer has too much "give" to ever sound right. It’s simply not designed to be a playback medium, he insists.

So while a great lacquer cut, properly processed, can sound better than a copper DMM, in the real world today, according to Calbi and Jensen, DMM yields the highest fidelity most of the time. Jensen didn't always feel this way. Early on, he went so far as to suggest to Sterling management that they send the Teldec developed system back where it came from. To his ears lacquer sounded much better; the DMM sounding bright and thin.

But the commercial reality was that DMM, like digital mastering was going to be demanded by clients, so Jensen (and of course disk masterers around the world) stuck with it, eventually getting the desired results. One of the early problems with DMM had to do with the "0" degree cutting angle and the severe equalization required to make it compatible with the normal 15 degree lacquer cutting angle.

End of Part 1