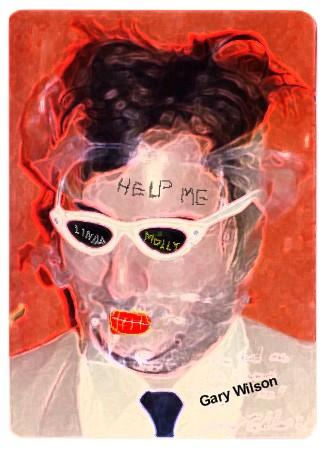

Gary Wilson

The point is: Gary Wilson is at heart a performance artist who is very serious about his craft. The person you see on stage and on record is a character, a very carefully constructed character.

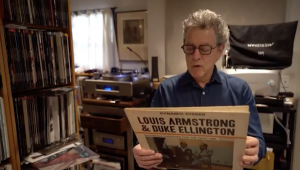

After the aforementioned Lincoln Center Film Festival viewing, I shared pizza and Apulian red wine with Wilson, two members of his band, and the film's director and producer. As we drank more and more, I watched Wilson and his buddies reminisce about the old days in Endicott, and the stuff they did and the people they did them with. It made me think about my friend Frank Doris. After I had turned Doris on to Wilson, I noticed how obsessed Frank became over this music and this man. At one point, I thought Frank had actually turned into Gary Wilson. Well, as I watched Wilson imbibe and discuss high school, music, and old Twilight Zone episodes, I finally understood. Frank Doris and Gary Wilson are actually the same person.

So, who would be more qualified to interview Wilson? The following is from an interview Doris conducted with Wilson in October, 2004:

—RJR

DORIS: OK, it looks like it's going. No dead batteries yet. I guess I'll get started, and like I said, I'm interested in asking some of the musical questions that a lot of people haven't asked because they tend to focus on other aspects of what you do. I'm kind of interested in the beginnings of your musical evolution because, obviously, your music isn't the usual C F and G that you hear out of most pop bands. It's more harmonically sophisticated, more keyboard-based rather than banging on a guitar. I'm wondering about how you managed to evolve that style rather than what most people would do.

WILSON: Well, I guess the story is my father was a lounge player, he played bass, so he was playing, you know the more sophisticated, I guess you'd call it in a jazz quartet, he played standup bass, they were an instrumental, but they played in restaurants. So, I was aware of that sort of thing because often we would pick my father up, my mother and I at one in the morning or something on a Friday or a Saturday, so I was aware of that sort of music and I started to get into the string section when I was young, fifth grade/fourth grade at the time too, so I kind of got an interest in that a little at the time, and I guess some of the teen idols were using some simple chording, like Dion, those type of people, so it all just blended into something, some people were more interested in kind of a blues rock type of thing when you were young and I went more towards the Mothers, Beefheart, the Fugs, plus maybe an interest in people like Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, everything just started blending in seventh grade. It all started coming to a head then. And then the Beatles came out, you threw that into the mix, there were all kinds of things that blended that turned into whatever it turned into.

D: I guess there's always that minority of people even among musicians whose ears are caught by different sounds, unique sounds I know Bob and I have always been that way.

W: It's funny because I guess you'd say I'd never really been into the blues that much, to tell you the truth, when I was young, I kind of considered it more of a jamming situation. You get together and jam on chords.

D: And either it's done right or it's the most boring thing in the world. Muddy Waters can pull it off!

W: You know when I ended up moving out here [to San Diego in the late 70's], that's what I ended up playing, with a blues band. I ended up playing bass with Roy Brown, of “Good Rockin' Tonight.” I played with him and Percy Mayfield and some of these blues legends that were from the early fifties and could actually be the fathers of rock and roll in their own way, so I got thrown into the mix with these guys for three, four, five years. I was real interesting. We had a gig at the Whiskey [a-Go-Go] at one time he was making a comeback like after. He wrote Elvis' songs, but he was like a blues shouter. He was a legend in itself. So it was great to have the original sax player from his old album. We were at the Whiskey and Eddie the Whip was the DJ host from Detroit who was specially flown in to introduce him, I guess he was the guy who brought him into radio in the late forties. It was great, we had the Sir Douglas Quintet open for us there, the energy was great. And then all these blues guys came out in their cars, with guys in their eighties and 70's paying respect to one of theirs of their time. It was great. Percy Mayfield, he's the guy who wrote “Hit the Road, Jack.” It was interesting the stories they would convey. So I got thrown into blues, I got to actually play with the real things, it was kind of intriguing. How can you play a whole night, four or five hours, of blues and keep it interesting? That's the secret, and we were able to do that. I really had kind of a blues awakening.

D: That's probably something I wouldn't have guessed. It's interesting because I guess most people (I'm just skipping around I have a few things written down because my memory keeps failing the older I get) a lot of reviewers would have never guessed that you've done any of that. They probably just think you're this mysterious, bizarre, freaky, twisted … They tend to characterize you by way of your music as this kind of strange, whatever, thing, and, on the other hand, I was always grabbed by the honesty of it, because, let's face it, most adolescent boys and probably a lot of men and they never get out of it, they've got sexual fantasies and fixations insecurities, lascivious thoughts about girls, but most people don't get to express it through their music

W: A reproductive thing. I guess deep down reproduction is the driven force behind it all, the whole sex business, really when you get right down to it. The finished thing, the ejaculation is done, you've tried to reproduce.

D: You've fulfilled your reason to be on earth but how do you feel when you read these reviews and people say, My God, this guy is totally nuts or totally bizarre or whatever when I think you're just honestly expressing what most guys would say if they could express it.

W: I'm just trying to do something. You try to find some identity in your music, and if that's the case, that's how it went, so be it, it doesn't offend me really. I've been noticing it lately in some of those Mary Had Brown Hair articles, where guys just come right out and say something like that. The only way I can describe them is crazy...

D: I think reviewers may sometimes get lazy and not really do their homework

W: There's a review of Michael's [Wolk's] documentary in the latest Spin magazine…I got pick of the month.

D: He did a really good job. I was really amazed at his finding all that archival film footage, talking to all those people he talked to in your past. How does that feel, as, you were almost in hibernation, and now of a sudden you get all of this attention as a result of the fact that album You Think You Really Know Me made an impact, an obvious heavy duty impact on a small number of people, but enough where ...it's like the “butterfly effect,” you made this wave 25 years ago and now all of a sudden it became this whole “thing.”

W: It's cool, it's kind of nice, it's great. Who would have expected it? After a certain amount of years you do succumb to your situation, you have in the back of your mind your fate. You give up on your dreams in one way, you do what you do, you stay active, you keep playing the lounges, keep playing some music for your therapy to keep going. Yeah, it's great how it's turned around a bit.

D: Yeah, it's nice to see, because I know so many musicians, for every one who makes it there are a thousand guys who are playing and who are really great and who have stuff…

W: Did you see how many were on that list on that CMJ thing (referring to the list of bands performing at the CMJ festival the week before in New York). Gosh, there were literally 200 bands, or something.

D: I know! And none of these are Britney Spears. They are all on one sort of fringe or another, but it's nice that you can always hope. I think what it all boils down to is that a lot of musicians do what they do because they have to do it. There's just something in you that needs to be done. I know, speaking for myself, I've always played, and I have recordings that, literally, no one has heard, not even my wife, because I'm in the basement and I feel like recording something. I just do it and maybe some of my friends hear it and it's just because you have to do it. I mean I'm wondering how young were you when you had that impulse that you knew you had to be a musician?

W: I was a member of the Dion fanclub when I was in fourth grade, so things started turning into a musical thing. I remember one time doing some sort of classical thing we were doing, probably with sixth grade, we were doing some solos against other schools, I was doing a bass solo. It dawned on me, I was very young, I was on stage and it was my first time on stage, you're in front of people, but of course when the Beatles came around it was a revolution at that point; everyone wanted to play in bands. You had bands on every two blocks. They had clubs for kids under age, clubs that would turn into psychedelic rooms. The Hullabaloo club actually had a franchise at the time. It was a marvelous time, you got into bands, and you saw all this and you wanted to play. The times were magical in their own way because I guess I started playing in seventh grade, and we would play every weekend because we had a good band with all these Italian kids in the neighborhood; there was good chemistry there. That was Lord Fuzz. And we would play with older guys in the other bands, and we'd pull up, we'd be 13 or 14 years old, the parents would take us, we would have gigs every weekend. We would play in some battles of the bands, it was a good time. It was a very harmless time. At the time you'd try to do the good songs. The Stones, Between the Buttons, some of those tunes; I always thought that was a good album. Their Satanic Majesties Request, it was their answer to Sgt. Pepper….

D: I'm curious, there you are in 1977, and you've got a Rhodes and a drum set and a Mini-moog and a guitar and I don't know what kind of fuzz box, and I'm just wondering how you found all that stuff, what drew you to them, and how you wound up acquiring all those instruments by the time you were 18.

W: I started with Wurlitzer electric pianos and graduated up to the Fender Rhodes and I acquired equipment ever since I was a kid so things just kept with me, certain things just stayed with me, some guys would let me borrow, the lounge band I was playing with when I turned 18 and I could play in the bars, a guy lamed Lenny Corrs [sp?] he used to play with Peggy Lee and actually Sinatra, and he was a good keyboard player and he had bought a Moog or an Arp and he let me borrow it and keep it at my house. Sometimes I'd go up the local university and go in their piano rooms and tape to try to get a good recording with an acoustic grand piano. At the time, when you got into that age group, guys were using electric pianos away from the Carpenters. Hey did you notice there's another Gary Wilson that does the Carpenters?

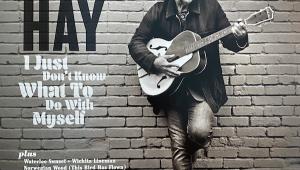

D: Yeah, I saw that on Amazon at first I thought it was another album that you did. Maybe you could cover one of their songs, “Goodbye to Love.” To segue into the stuff you used for Mary Had Brown Hair on the poster they gave out at Rothko's I noticed there was a picture of a Casio. Obviously you're using some drum machines and stuff for some different sounds for the new album.

W: Yeah on the new album, I'm using a Casio, it's a pretty good unit. It has separate outputs for every single drum. Actually, Butch Bottino, who played with the Blind Dates sold me that. It works good, I always prefer real drums, especially when I play live. I had another Yamaha keyboard that I used that I use in my lounge act.

D: And you're still recording into the Teac reel to reel?

W: No, I actually ended up buying a Tascam 788 Portastudio. It works good, it has a hard drive.

D: Yeah, and when you listen to the Stones Throw release of Mary Had Brown Hair and compare it to the original version you released on your website, it doesn't sound as if there's a radically huge difference in the sound.

W: We went back and forth on it. I said try to get it as close as you can. I think the volume could have been lifted on a few tracks, but, yeah, I think they did a nice job. He just joined them a little bit closer and dropped out a few songs.

I saw in [NY music retailer] Other Music, they had the cover of Mary Had Brown Hair in the window.

D: I notice you use that effect where you, don't speed it up, but change the timbre of your voice, sort of having it in the third person, someone singing about you, I'm wondering how you discovered that, as it's throughout the album.

W: It's a color, it adds a kind of timbre to the music. I used to go really wild on the old tapes, manipulating some of the voices. I would submit them to ESP records.

D: In those days it probably wasn't all that crazy or outlandish. It wasn't as if you went to the offices of MTV. ESP would have had an ear for it. You could experiment in those days.

I'm curious, as one musician or another, do they pop into your head, or do they come to you in a dream, or do you have to hash out two years…

W: It's a long process in some ways it's eliminating, you try songs, you sit at the keyboards as some ideas come to your head, and went it all comes together it's magical. It's not the finished thing, but you're close to it. It is a process, it is slow sometimes, you go back and edit yourself a lot, and there's much stuff you throw out. Sometimes maybe a string arrangement you add; you try different things. And when you hit it, it's exciting. You finally know you've got something you can stamp your name on it. And if it works out audio-wise, you're got it going. You've got the fidelity too, and that's imperative.

D: It seems like you still like to sing about women a lot. I listen to your stuff, and I have a young daughter and she'll say: “Why does he always sing about girls?”

W: I guess it's the Dion and Fabian thing.

D: You listen to 90 percent of what people sing about and it's relationships, they're singing about, well maybe some times they're singing about their car, but then it's just my car as a love object, you don't hear people singing about quantum physics or how to build a bridge.

W: Maybe like Zappa when his lyrics started going out there. To me, my favorite albums, and you agree on some of them, are Absolutely Free and We're Only In It For The Money Those are the landmark ones for me.

D: Speaking about myself, I don't know how I got into this kind of music, I know that at a young age, I knew that a lot of the conventional pop music was boring crap. Someone once asked Theodore Sturgeon, the science fiction writer, “90 percent of science fiction is crap” and his reply was “90 percent of everything is crap.” It's hard to say why you're drawn to the more innovative or experimental kind of music.

W: It's just something I got into very young, the more experimental I got, the better it got.

D: In the 60's and 70's you could do that, today, if the band wants to go the whole major label route they can't think of that. Although I wonder if the internet will be a great thing for musicians, as it will give a medium for musicians who are not played on the radio to have a medium and I think it's great.

W: When Motel dissolved, I had that period between Motel and Stones Throw, where it feels so much more comfortable when you have a label over you, I can tell you a story, where I submitted the same record to the (radio) station and they decided not to play it and then Stones Throw reissued it and they played it. So it's like you need that little umbrella over your head to do certain things.

The computer is a major development as it's a record maker, a far cry from the old days with those do it yourself record makers in the carnivals and amusement parks.

D: For 25 years you were very difficult to reach, and now you have a website where people can email you. What kind of effect has that had and what kind of people contact you?

W: It's kind of interesting in it's own way, I don't mind talking to people, fans in their own way. It's far cry from what it used to be with no phone…It's fun, I get a lot of different things from different people, mostly positive stuff.

D: I guess you must get crazy people.

W: Yeah, I get one guy who called me saying he's going to download me for free and then he slammed the phone down.

D: So do you figure you'll be playing more gigs?

W: I will be playing a few more, I'll be coming to NY, I wouldn't mind coming to Philadelphia. That could be fun.

D: Some of the major cities could be cool, some of the fringe places.

W: I was scheduled to go to London with PB Wolf but then it got too stressful as I just did Hollywood, and then NY and then going to London after three days was a bit too much.

D: I guess you got to know the Blind Dates in high school, but how have you managed to keep in touch with them, you have a lot of the original guys still playing with you.

W: Actually, it's neat to be able to do that, to be able to play with people I've known for a long time, guys who have stood by me in thick and thin. It's great, when I did that homecoming show [in Endicott] it was kind of a wild one as you're down there and people from my past, my aunt was there, she's 93, and then younger people, people I hung out with, the Putrinos, and I'm walking around with all of this flour on my head and no one was thinking anything about it.

D: After the Rothko's gig, I was looking for you and they said, Gary's outside, and you were standing out there wearing the whole stage regalia with the sunglasses and the flour all over you and you're standing there on the street in Manhattan and no one is giving you a second look.

So even though you had no phone, at least one of the guys in the Blind Dates was able to keep in touch with you.

W: Yeah, Vince Rossi, he was the one who put me in touch with Motel Records, so Vince I always like to include him. When we did the Hollywood gigs, we did the two guys who did the “When I Spoke For Love” single.

D: Yeah, I bought that single at CBGBs. I never had the You Think You Really Know Me album, I had a tape from Bob, and when you were selling it at CBGB's, there I was a kid making $8500 a year and I asked how much it was. Ten dollars. Ten dollars? That's kind of steep. And Bob is like, What are you crazy? You're not going to buy this thing? Every time I lend this album to you I'm afraid I'm not going to get it back. How many times would I have kicked myself if I didn't buy that album.

W: It's getting rarer and rarer. The original one.

D: It's amazing how many musicians don't have copies of their older and rarer stuff.

W: I don't have a copy of the single we were speaking about.

D: I think I only have one.

W: That's okay. You keep it.

D: When you grew up in Endicott, was it really an isolated small town?

W: You're right, it was near Binghamton, so it wasn't like being in an isolated small town, like the little towns scattered around Lake Ontario. You have a couple of colleges here. Nam Paik, the experimental video guy, used to come to Binghamton for the experimental video studio and we had access to all this equipment.

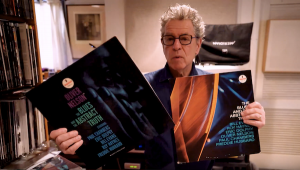

D: McIntosh was there, so you had high end audio.

W: The guy who did the pictures for a lot of my covers worked for McIntosh and his whole cellar was filled with McIntosh amplifiers. Tubes laying around.

D: I still have an MC-275.

W: Yeah, that's a sweet one. He had a tube preamp, tuner, and power amp, and an Altec with a coaxial driver from the 40s and 50s. He had that in his living room so I knew what good sound was at an early age. I had a Harman Kardon Citation amp and they'd bring their McIntosh over and I thought the Citation sounded better.

D: I have a Harmon Kardon 230 that I listen to in the office and it still works.

W: If I was a wealthier man, I'd like to collect one Citation from each year, they brought in a different designer each year. I paired it up with a Dynaco PAT-5. I thought there was a big advance form the 4 to the 5, had more of a McIntosh creamier tone.

D: So it wasn't like you were living in the middle of nowhere. But in your music, you still write about Endicott. The point is, you've been living in California for 25 years and you don't make any references to it.

W: Maybe my roots are upstate New York, because I'm thinking of moving back to New York anyway, not this year, but I've been out in California a long time now. Vince and I have talked about, that if I ever moved back, I could move back and get together with the old guys. Vince said of Rothkos, “This is like a Blind Dates gig from the old days.”

D: The audience was very enthusiastic for that show at Rothko's, more so than last year's show at the Knitting Factory. And you guys played fabulous! It was a terrific show!

Bob and I were talking as we drove into together and we were driving over the Williamsburg bridge to Manhattan, and we were saying, when was the last time we drove over this bridge together to see a show, and we realized it had to be the 70's!! It was like we just went into a time warp.

W: It's funny you say that, because the day after the show The Blind Dates came into the city. We were on Mulberry Street and I had to walk away for a second as I thought I was back in the sixties, taking in the ambience.

D: You have to rejuvenate yourselves once in a while. I felt like I was 25 years old again and going to the clubs. Music is this mysterious thing. You're connected to it.

W: I put on Vaughn Williams sometimes and I always listen to it sometimes and it's nice and when you play with your friends it's even better. I use music as the guiding force.

D: Well, I'm starting to run out of tape.

W: If you have anything else, just give me a call.