Ray Davies: One of the Survivors

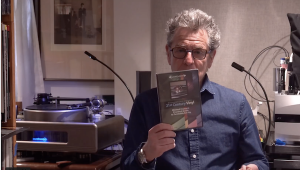

The door to the Velvel Records reception area opened a good dozen times while I awaited Ray Davies' arrival. There was a constant stream of FedEx and UPS delivery men, visitors, and Velvel workers. Each time it opened it could have been for Davies, but I knew it wasn't, though the door opened toward where I was seated, blocking my view of the entrant.

With a click of the knob and a rush of air, the door opened one particular time and I knew immediately it was Raymond Douglas Davies' entrance. I would have bet a hundred bucks and I would have collected. What told me? The panache with which the door flew open? The “vibe?” I don't know. I just knew it was Ray, and it was.

Whatever “it” is, Ray Davies has it. He's had it since “You Really Got Me,” and probably before that as well. For over 30 years Davies, leading The Kinks, has fascinated and mesmerized music fans - first, aided by brother Dave's heavy axe, as a power-chord-charging, but somewhat bemused, hard rocker, then, during the 1970s, as a campy, theatrical, politicized conceptualizer, and finally once again as the leader of a no-nonsense rock 'n' roll band.

Over the past few years Davies, estranged from his brother and The Kinks, has been on a solo tour, reading from his “unauthorized” autobiography, X-Ray, and playing songs from his rich repertoire to adoring crowds around the world.

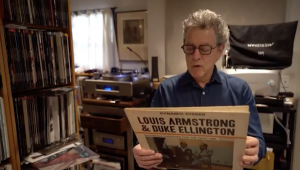

This interview was occasioned by Velvel's reissues of The Kinks' RCA and Arista catalogs, which Rhino had covered on CD not too many years ago. I sat down to talk with a healthy-looking and quite fit Ray Davies (looking younger than his 54 years) in an acoustically disastrous meeting room at Velvel, engendering the numerous brackets around certain inaudible words in the transcript.

While Davies has a reputation for being a tough and sometimes surly interviewee, he was solicitous, courteous, and engaged throughout the forty-five or so minutes that I spent with him.

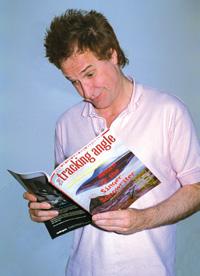

-MF

Michael Fremer: You know, I'm glad I finally got to interview you at an age when I'm old enough to really appreciate it!

Ray Davies: We didn't do this before? I could have sworn we've done this before.

MF: No, I've never met you. Well, I met you once, actually, back in 1973, it was in Boston, I was a disc jockey on WBCN and I was in my disco phase and I was pathetic and I walked into, it was at the Holiday Inn, and I walked into the room - and I won't even talk about how I was dressed - and you took one look at me and you let out a noise….

RD: Are you sure it was me?

MF: Oh, it was you! You just looked at me and the noise you made, you groaned and you literally exposed me for who I was, and I just left. (laughs) It was really sad!

RD: (laughs) Oh, no! I'm sorry!

MF: No, it was good, actually. I needed to hear that. I was so disappointed. (both laugh) I wasn't going to mention that to you, but I had to do it.

RD: You had to do it.

MF: Yeah, and I thought I was so cool, but I wasn't. It was horrible. I want to start by talking about fanatics. I have some friends who are adults - professionals with families, yet they are so fanatical about you! They spend their spare time online on some Kinks chat line talking about you and everything you've done.What do you make of that? Do you reserve that level of fandom for anything in your life, whether it's music or sports, or stamp collecting or whatever?

RD: I think everyone has the right to be obsessive about what they're doing. If I'm interested in something, I want to know all of the details. I don't think they're extraordinary or have a problem at all. I think they're just fascinated. I think what spawned it is, I made a decision in 1972 that I'd never make a lot of money doing this, so I'm going to do it the way I want to do it. And I started consciously to look, to search so that my projects have back stories to them. Every album I've done has a back story and so I get literary (inaudible) and I do a lot of research before I embark on what should be a very simple thing: to make an album.

Muswell Hillbillies I think was really the first. I'd done a lot of that but I hadn't really thought about researching it myself. I wanted to make it as interesting for me as possible, so the amount of research I've done, I'm not surprised that people started to pick up on it. I was putting as much into it as writing novels. And so I'd say that people were interested in finding out what my idea was, so I'm not amazed that people are interested and want to find out about that. How far they go is up to them. People have an insatiable need for information and the opportunity is there to get that information, so if people want to spend time doing that, I applaud it and I hope they enjoy it.

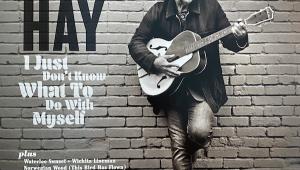

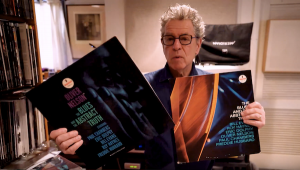

MF: The event which occasioned this interview is the reissueing of the RCA and Arista catalogs. When I heard that Bob Ludwig was doing the remastering I called him and asked whether I might come up there and….

RD: You got through?

MF: Oh, I know Bob. We go back…we've had contentious arguments for over 10 years about sound and analog and digital and records and CDs, but he tells me that you would not supply him with the analog master tapes of these releases. Instead you gave him a hard disk already transferred from the analog tapes.

RD: What we transferred…I tried to track down as many original masters as I could. A lot of them were still with Arista and I was scared of transporting what existed because we had such a hard time getting masters back from Rhino of the RCA tapes.

MF: Really?

RD: Yeah. And I was terrified of transporting them to America so I just copied them to DAT. I took great care with the gear I used to do it. I used Apogee [analog-to-digital converters] and I was concerned that the masters stay home. When we assembled the thing down at Toy Specialists [in NYC], we didn't know then who would be mastering it. You know, I would have sent them to Bob, but I don't know what Bob's [duties] were as an engineer. The last place - when he was at Masterdisk - he didn't cut everything I thought he should have cut.

MF: He cut Sleepwalker and -

RD: Oh, he cut a lot of stuff and we only went elsewhere when he couldn't finish it. And I didn't want to give it to some unknown assistant. So I didn't deliberately not give him master tapes.

MF: But you got all of the RCA tapes back?

RD: We got most of them back. Fortunately, the ones that were slightly damaged, which I felt concerned about, I had taken the time to make really good copies.

MF: And you still have the multi-tracks on these things? Which is something you don't have from the original Pye releases.

RD: No, they exist! They swear they don't have them, but I know they do.

MF: Really? That's a big bit of news! So you did the transfers, literally yourself?

RD: Yes, of the RCAs. The Arista things we got back from Arista in New York and those we put on hard disk.

MF: And those were transferred at higher resolution? 24-bit, 96 K sampling?

RD: Yeah.

MF: You know they're releasing consumer discs on that format now.

RD: That's great. I mean, that gets as good as it gets, but it wasn't my choice to not give him tape, we didn't even know [Bob Ludwig] was going to do it.

MF: So you sat there and….

RD: For the most part. I wasn't there all the time.

MF: Are they straight transfers?

RD: Relatively.

MF: So that Bob has the final.…

RD: I copied some things with the Apogee that were obviously not the original, but I didn't have the original, it was what I had. And it was flat.

MF: I know this is mundane stuff, but people are interested because this is a reissue project. I'm interested in your studio - Konk studio. What is that exactly? Did you build it from scratch?

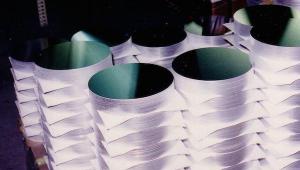

RD: Yes. We bought it in the early 70s to actually rehearse in, then we bought a tape recorder - an Ampex 16-track, a desk [British for mixing board], so we had a studio to do demos and then we started doing our masters there. Then we built the Neve room with a wonderful old desk - I forget the actual numbers.

MF: Is it a tubed board?

RD: Probably; we bought it off of Pink Floyd; it's the desk they used to record the movie The Wall. And I've been offered so much for that desk every year that I'm tempted to sell it.

MF: Well, there are good-sounding boards and bad ones….

RD: We get people coming in from all over just to use that desk to do overdubs. And in the other room now we've got an SSL [Solid State Logic].

MF: That doesn't sound as good, does it?

RD: Ah, well, we've got a few Neve modules in there. We can probably make the SSL sound as close to the Neve….

MF: By swapping out the modules.

RD: Yes.

MF: Were you unhappy with the Rhino transfers?

RD: To tell you the truth, I didn't hear any of them. I'm sure it's improved, though, because the CD actually does - you hear tom toms, your hear snap, you hear echo that got lost on vinyl. (Ed. Note: Rhino's RCA reissues were on CD)

MF: Well it depends on who's mastering and who's playing it back. I mean, I'm a vinyl fanatic, but I don't want to get into that….

RD: I think there's one interesting point and you may come to it. One of the records Bob will remaster, two records actually, is [One For the Road] where he will have the original tapes because I suddenly realized when we got the tape from Arista back - that we didn't [already have them] - an argument was made if possibly we could take it and…sometimes you have to sweeten the adjoining [tracks] because I wanted it to be as continuous as possible, so rather than have a fade-out, a spiral and then the next track, I wanted to crossfade a lot of stuff so we had a tape running so it just fades out while he's mastering and (inaudible).

But the tape that exists is just the bare tape with the edits, so we'll put that into the digital domain and then cross it as smoothly as possible. The real challenge will be with [Give the People What They Want] because that record was designed for vinyl. I recorded that with a lot of ambience because I wanted that record to reflect the gigs we were playing. We were playing large auditoriums and the record was designed to be heard from around the 60th row. So you're aware of all the “smack” and all the ambience. I say “smack” - that's what I mean by ambience. “Slap-back,” and it's deliberately recorded like that. And I don't think you can get that level of compression on CD. It would sound too clean. If there was some way you could actually do it through a lathe first and then go to CD. I don't know, but it was designed to be heard on vinyl.

MF: Well I'll be interested to hear that when it finally comes out.

RD: Well, that might be a challenge for [Ludwig].

MF: How's your hearing, by the way?

RD: Remarkably good. I have an ongoing sinus thing I've had all my life and I have it checked. It's much better now that I'm not touring with The Kinks because I [used to] stand slightly to the right of the stage and play loud, and I used to get “deaf ear” from the side fills (speakers). I don't have that so much now.

MF: You don't have tinnitus, the ringing-in-the-ear thing?

RD: No, thank God. I think I've got a slight bit in the left ear but I have it tested regularly. The last time I had it tested the doctor was amazed what I could hear even though I have a [frequency] dip. My “tuning” is really good. I listen, when I mix records, very intently. I mix at the lowest possible level so we even have to switch off the air conditioner. I've started [physical] training and now I'm taking care of my eyes because your eyes need exercise and you can exercise your ears as well.

MF: I spent this morning interviewing George Martin. I'm curious: do you think about what would have resulted had you used someone like him as a producer instead of Shel Talmy and EMI as a record company instead of Pye?

RD: (long pause) I think I would have liked to have worked with someone like him, with his musical expertise, but I don't [know] the real story of his producing - of who really came up with all of the ideas. When those things happen I think you always think of the same things at once and agree it's the right thing - how fast do you take your crossfade, all that stuff. But I would have welcomed someone with his musical expertise, without doubt. I'm not sure - I think The Kinks records might have sounded a bit too correct.

MF: That's the point I was going to make. Would it have been too clean?

RD: Uh huh. I would have loved to have worked with him just to get the denseness in the recordings, the depth. Things like “Ticket to Ride,” the guitar. It's only a couple of instruments but it sounds so complete. I think it has to do with mixing.

MF: And the facility itself, EMI studios. What were Pye studios like in those days? I have this picture of this slapdash kind of -

RD: It was remarkably well organized. Number one room at Pye was great. They did a lot of orchestral stuff there.

MF: Was it a big room?

RD: Yeah.

MF: What was Shel Talmy's input into those early records? What was his producer's job?

RD: He was there from the beginning as a marquee value. We went in with a package: “Shel Talmy's going to produce this new band The Kinks.”

MF: Had he done other bands like The Who first?

RD: No, The Who came a long time after.

MF: Oh, right! So who was he….

RD: He'd produced a few records with a guy named Mike Stone, Talmy and Stone productions.

MF: He was American, right?

RD: Yes.

MF: Still alive?

RD: I think he's on the coast. I think Shel…he was one of the silent producers. He didn't say much but I think he was good at his work. He would say, “a bit of compression,” but we worked with really great engineers. We had a man named Bob Auger. Bob is still doing records, I think. Probably would be known to George Martin. He was one of the great technical guys. And we were fortunate to have guys like Bob around because it could have been slapdash. And it was like an indie label. So we needed their input. I think Shel was looking to people because he was a rookie, too. It was a wonderful thing. We were all learning, all experimenting. It was like George Martin - he worked with the prefects, “the head boys” in the big school. We were like the renegade kids on the block doing our own version of that.

MF: That probably worked out better for what you were doing. Is it always a good idea to let artists take control of their reissues? Isn't there a chance they'll use the opportunity to “rewrite history” and change things?

RD: I don't think it's possible if you go with the original tapes. How can you?

MF: Well, if you go to the multi-track and remix.

RD: I wouldn't do that.

MF: Some of the hard-core fans are disappointed with the sound quality of the Pye reissues. They would have preferred stereo if they were available. Were they available, and did you choose the mono mixes because that was how they were meant to be heard?

RD: “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All Night,” that period, were mainly mono and they only did that electronic fake stereo, so if people want to hear that, they're welcome to.

MF: Well that's bad, but the first album I have a version Mobile Fidelity released that is stereo.

RD: Are you sure?

MF: It's got a voice here (left) and a voice here (right).

RD: That is fascinating.

MF: The second album was mono. They put two albums on one disc. But the first one was stereo.

RD: Every track?

MF: I don't remember.

RD: I guess [if] certain tracks were recorded four-track, I guess I would have separated the voice. But they would say, “Here's an alternative mix” and it was the same track but with a vocal over on the other side.

MF: Did they just take these old tapes and transfer them and touch up the EQ, or did they try to get rid of any of the noise?

RD: I think the way to get them as “fat” as possible is to give someone like Bob [Ludwig] an opportunity to tinker with it.

MF: I mean the Pye issues. You were heavily….

RD: I wasn't invited to go along.

MF: You weren't?!!

RD: No.

MF: You know, there's a guy online from Pye who says that you were in charge of that entire thing. That it was your operation. That you controlled everything.

RD: I only found out where they were mastering it when it was too late to go down there. They had finished.

MF: Amazing. What is the….

RD: I don't want to create a controversy about it, but they did pay me, they did send me the advanced copies.

MF: But that's too late at that point.

RD: And I sent back notes saying, "That particular track is a copy of the master. That's not a master." Because my memory is really spot-on. And when I used to make records for Pye, number two was a nice room because it was a small control room and I judged the power in my chest. I felt the sound hitting me. And you know when it's a master. Copies don't really hit you properly. And I know a few of those aren't the masters, whether they're in the dustbin, or they've been shipped abroad, or whatever. Because Pye was sold to Castle Communications and they probably moved the tapes around and mixed them up. But I know they all exist somewhere.

MF: What's your feeling on bonus tracks? Fanatics want every last scrap of things you recorded. But is that like feeding guests leftovers? I mean, someone said there are two tracks from State of Confusion that only appear on cassette. Will those be on the CD?

RD: Probably.

MF: Why were they only on the cassette?

RD: Bob Ludwig can answer that because I make long records and the time with vinyl is about 25 minutes a side. I've always been conscious of trying to make long records. I used to annoy Bob, I think, by going in there and standing behind him and saying, "Give me some more edge there, make this louder," and he was very aware of that. It used to frustrate me, actually, near the end - vinyl - because I dread the whole mastering process because I knew how great the record should sound. And when I made the records, like Muswell Hillbillies, I made it right on the edge of being dull, but it wasn't dull. I mean, the tapes were never dull and so it's a crucial moment when you go in there and a guy listens to a tape for the first time and he's unconnected. You know, he's a technician. "Uh, dull. We need to cut the bass and put a little brightness in." That changes the arrangement. Some of the instruments are mixed to be in a certain zone, you know. As soon as you add that brightness, it makes it lumpy.

But there's a double issue. He's looking at technology as well. But my concern was always that they would change the arrangement. And when I finish mixing an album and I assemble it in the studio, I always wave goodbye to it then because it will never be…. I spent so much anguish mastering tracks in New York - and it has nothing to do with Bob, 'cause he's great, but playing things back and saying it's not the way it sounded in London, it's not the way the tape sounds.

MF: Do you really think that a CD sounds like a master tape? The frequency balance may be there, but isn't it fundamentally changed it some way?

RD: Oh yes! It's not sitting on anything. I can't explain it any other way.

MF: That's exactly right! It just doesn't have any gravity. But it affects the music. It affects it in a fundamental way. I can't just sit and listen. Well, now with 20-bit mastering it's better, but originally, it was like, "Where is it?"

RD: I agree.

MF: So will Return to Waterloo be reissued?

RD: This is a weird project because it has to be, it's a project Arista didn't want because they saw it as a film that has a soundtrack and it's outside the Arista agreement. And I've been tracing it down and nobody's claiming to own it. But The Kinks own it because they didn't charge for the mechanical rights, so The Kinks should get royalties of, I don't know, $10,000 or something. I have to recoup that. I'm not sure who owns it. So what we'll do with that is we'll resolve it somehow…and I've got all the film clips and I'm going to dub it all to video and turn that into the project that it should have been. Because I had to cut that on a Steenbach - an old-fashioned film editing machine - I really pissed the TV company off. I went to upgrade every shot. They really hated me. I was there for a week and normally they just cue up the first shot and run it off. It's like the guy hearing the tape for the first time not listening to the arrangement and just putting top [high frequencies] on everything.

MF: So you're going to have bonus tracks on -

RD: I'll tell you what's interesting: on Muswell Hillbillies, there are two tracks, one I knew about at the start of the recording, called “Mountain Woman,” and there's one I found at the end which is a first take with a first vocal called “Kentucky Moon,” that I'd even forgotten I'd written.

MF: You just found it in the vaults?

RD: It was on the end of one of the reels of one of the songs. It was on the same reel as “Complicated Life,” on the same day. And “Complicated Life” must have been done near the end of the album because maybe we thought we had enough songs. I'm really pleased with “Kentucky Moon,” because it offers an interesting insight into the band. I mean literally we had one take for it. So that's the value in bonus tracks.

MF: Yes, but for the most part you don't want to release whatever scraps….

RD: No, I don't want “Dedicated Follower of Fashion,” the same session, same mix, but the vocal stuck on the right-hand side.

MF: There's a certain phenomenon when an artist signs with a new label; there seems to be this kind of liberation: the direction of the music changes. When you signed with RCA, that's when you got into the concept albums. When you left RCA and went to Arista you went back to a hard-rock sound.

RD: Exactly. Politics and art and commerce and art join hands at that point. Muswell Hillbillies is the album I always wanted to make at Pye, but I knew they'd never promote it, they'd never do anything with it. It happened that RCA was good to us, it's what they wanted.

MF: Did they expect to get a rock band and then end up getting a theatrical, music-hall type of band?

RD: That came later. I mean, it was a rock band - a hillbilly-type band [that] they got.

MF: What made you put the “Day-O” song into your act?

RD: Oh, I had a Stan Freberg record when I was a kid and he did the banana boat song. "You're too loud, man, you're too loud." And that became part of our joke - an in-joke with the band. I did it one night on stage and the audience responded.

MF: Have you ever heard of Irving Burgie?

Ray Davies: No, I can't say I have.

MF: He wrote “The Banana Boat Song.” (MF hands Ray Burgie's Angel Records CD)

RD: Really?

MF: He wrote all of these songs that we think are public domain.

RD: “Day-O”?

MF: Yes.

RD: So does it go under two names? “Day-O” and “The Banana Boat Song?”

MF: It says “Day-O” on his album, so that's what it must be.

RD: And he wrote “Yellow Bird”?

MF: Yes. He's a Juilliard, classically trained musician. He had a recording and performing career as Lord Burgess.

RD: Really? Well he should be looking for a new label because Angel isn't anymore.

MF: You've written a great deal about class and politics. Do you think one can really grow out of one's class? Or is there a permanent kind of status that remains so that no matter how much money, fame, or success you achieve - even in America, which is supposed to be a classless country - you can never really get past it?

RD: I think you have to go under an immense amount of psychological rehabilitation to change your origins, and I feel my current displeasure with Britain is - for the first time in my life I'm considering leaving England. I still live there. I'm considering getting out, not because of money, or taxes, because the tax breaks aren't that bad. I just can't stand what's happening to the culture. We've got a middle-class man the head of a working-class party. And I hate him [Prime Minister Tony Blair]. I feel it's a betrayal of the English people.

MF: What's it like doing a one-man show and reciting prose?

RD: It was daunting at first, but I was lucky. I'd done the show just as reading alone when I started. I was doing book readings to sell my book and I got bored with that, being young at heart so I put music to it. I'd done the readings to begin with and the music just liberated it.

MF: When you read in front of people is there a certain sense that something's not happening that you are used to having happen when you're in front of people on a stage?

RD: At first. The first time I did the show as a try out, the next day I couldn't walk because my legs, my shins were bruised, my ankles were bruised because I was stamping my feet real hard to compensate for not having a rhythm section there.

MF: Did you have to build a rhythm section into the words?

RD: Yes; I found it not transcendental, but you have to concentrate and internalize your rhythms more. In a rock band you externalize and jump up and down more.

MF: Did your words seem completely different when you were reading them out loud compared to when you wrote them?

RD: Not so much, actually, no, I can't say that. I could think about the meanings more. When you're playing with a band - when I wrote the songs I knew all the meanings, when you make the record you forget about it, you're concentrating on the mix, and then when you play it live, you forget about the meaning, you're just struggling to get your voice heard over the drums and guitar, but then this allowed me to rediscover the music again.

MF: There's a kit Velvel sent out with this reissue series and it uses The Kinks in the present tense with both you and Dave being in the band. Is that possible?

RD: What? "The Kinks are"?

MF: "The Kinks are." And you and your brother, you know.

RD: I think my brother is there as much as he's ever been, particularly with a reissue, because when it's a reissue, you are there.

MF: Well, yeah, but is there any chance of a live….

RD: Eh…em, em, em, it won't be live, it might be a studio.

MF: It might?

RD: It might, yeah.

MF: So how does it feel to be Ray Davies today and how do you think the world is treating you?

RD: Well, it's treating me alright. I'm just, as usual, my own worst enemy.

- Log in or register to post comments