The status check contributes to fraud prevention by allowing applicants to confirm that their details are correct and that no unauthorized changes have been made to their applications with Srd status check . If discrepancies are noticed, individuals can report them immediately, reducing the chances of fraud or identity theft. This security measure helps maintain the integrity of the SRD grant program, ensuring that only eligible beneficiaries receive financial support.

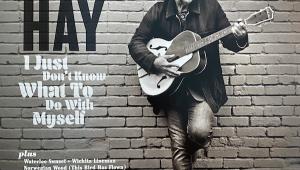

Veteran Recording Engineer Roy Halee On Recording Simon and Garfunkel and Others

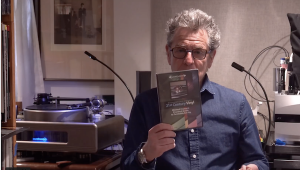

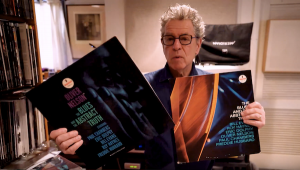

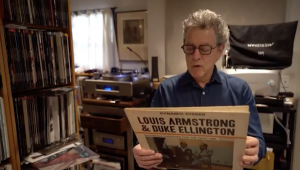

(Photo: Roy on the left, Wilson Audio Specialties' Peter McGrath on the right, Wilson Alexandria X2s in the middle).

You won't find Roy Halee's name on many great sounding records. Not because the veteran recording engineer hasn't made them, but because Columbia Records' policy for many years was to not credit the engineer on the jacket. So, aside from the few that do credit him, the others require you to know who they are. That's one reason I tracked Roy down through Sterling Sound's Greg Calbi who has mastered many of Halee's recent projects. But more importantly, as with Bill Porter, I just wanted to sit down face to face with someone who has consistently provided us with great sound, and find out why and how he managed to do it, when so many others failed.

Some of Halee's recording credits are well known:all of Simon and Garfunkel's records, the best sounding Byrds albums (Notorious Byrd Brothers and Sweetheart of the Rodeo), and of course, Paul Simon's two fascinating and extremely successful projects (both commercially and artistically) Graceland and Rhythm of the Saints.

Halee, who grew up in the New York metropolitan area, comes from a musical family. His mother played violin in Al Jolson's band. His father was the original singing voice of the cartoon character Mighty Mouse among other musical credits. His sister sings opera professionally, and Roy plays trumpet for his own amusement. Despite his long association with pop and rock, Halee is a devotee of classical music-especially opera.

While some people leave their work in the office, Halee has no problem taking it home with him. Nor would you if you had his stereo system, which includes a Rockport System III Sirius, Wilson Alexandrias and one of Wilson's refrigerator sized Xcess subwoofers.

MF: As an engineer who's been around for awhile and who knows what good sound is, how do you reconcile that with the need to make records that sound “contemporary”-usually meaning not good sounding. How do you balance those conflicting sensibilities?

RH: That's a good, good question. First of all, I come from the school of making pop records, where you have to get it and you have to get it fast-that's where I came from at Columbia Records. The arranger is out in the studio running down the tune and by the time that's done, you have to have the sound because he's got to do four songs in three hours-and that includes possible overdubs. So you've got to get it fast, and sometimes sound has to take a backseat.

MF: How did you get started at Columbia?

RH: I began at Columbia's classical division. I was laid off at CBS television, a hundred guys were laid off.

MF: Interesting, because that's how Bill Porter got started. He was in television and got laid off and ended up at RCA Nashville.

RH: When I was there, they were doing Gleason, Playhouse 90, and all those shows-live. I was lucky to get into the record side-because my father was in the business, a singer. Mitch Miller got me in actually-and I started editing tapes of classical performances. This was in the late Fifties-the stereo era had begun.

MF: And you worked down at the East 30th Street studios?

RH: Well, no. In those days, the studios were studios, the editing room was an editing room, and the mastering room was a mastering room-all separate. Dates were done, the tapes came into an editing room where they were edited and mixed down to a two-track and a mono, from there to a mastering room. I found myself in an editing room, editing a lot of classical music-which I like, because my real love is classical music.

They started occasionally sending me on remotes-to Manhattan Center to run the tape machines, whatever. Gradually they were breaking me in. And I found-I was a little disappointed-that there wasn't a lot of experimenting going on. It was a set thing. You go in, that mike goes there, that one there-ten AKG C-12s up there and boom boom boom! It's done the same way every time and nobody changes anything. They used a lot of mikes on a symphony orchestra in those days.

MF: An didn't they add a great deal of artificial reverb to those classical recordings?

RH: Well, not necessarily to the Manhattan Center recordings. But that was the so-called “golden age” at Columbia. They had The New York Philharmonic, The Philadelphia Orchestra. And I think some of the stuff done in Cleveland was a little dry.

MF: Well there's a very famous story about George Szell having an AR-3A under his couch and he'd bring a temp mix back home to listen, and he'd say “Too much bass!” So they'd turn it down, and those recordings ended up bass-shy.

RH: I believe that. You should talk to Buddy Graham [a still active remote engineer who recorded the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Mormon Tabernacle choir among many others for Columbia Classical Masterworks].

MF: That's probably one of the reasons the Columbia pressings are out in the bins for a few bucks while the Mercurys and RCA-well you know.

RH: Well I have a lot of those wonderful old mono Mercurys and I noticed in the notes how they were recorded using one microphone hung directly over the conductor's head…that's what I grew up with though I learned fast that that is not always practical!

MF: At that point, Columbia wasn't doing much rock and roll.

RH: No. Mitch Miller who was head of A&R did not like rock and roll. He was a pop man. Sinatra. Percy Faith. So somehow I was able to break out of classical editing and do more pop editing, like Steve Lawrence and Johnny Mathis. And I'm thinking to myself, musically I don't really love this, but it's more fun, more challenging.

MF: What kind of editing was involved in that? Did you splice-in during takes?

RH: Absolutely. Tons of it. There was always a breakdown. First of all, it was always three-track and if there was a breakdown they'd make an insert for the error.

MF: Breakdown in what sense? Technically or musically or both.

RH: Well, there never were any breakdowns technically at Columbia, in my experience. They had really fine engineers-super engineers-guys like Fred Plaut and Frank Laico and a terrific maintenance staff! And the producer of the session would have it all laid out for the editor before we got to it. Editing the three-track would go on for several days to compile an album.

MF: You weren't at the sessions then?

RH: Occasionally they'd send me up to run a machine. Or I'd be a back-up, or I'd peek in to see what was going on. But mostly I was doing editing and remixing. I did that for about a year and a half and I started to get good at it. And I started to get requested by A&R guys who'd say, “Hey, let's use that new guy…”

MF: And part of that is personality-the way you relate to the artist?

RH: Absolutely. That's how I got in with Steve Lawrence and Edie Gorme. I remixed “Go Away Little Girl,” and it was a number one. So I got popular. By then I really wanted to get in the studio and do a lot more remixing.

MF: Who taught you how to edit tape in the first place?

RH: Well, the people at Columbia when I switched over from television. When I saw how these guys edited-particularly the classical editors-they could cut on a string legato, and cut on the “eeee,” and scrub it and hear it and I'm saying “What the…! What are they hearing?” And I mean they're not going back and forth 25 minutes. They rock back and forth three times and there it is!

MF: Did they read music?

RH: Of course. But you always had the A&R man there because it was a union rule. And I never thought I'd get in the studio because of seniority. But lo and behold, they put me in one day to do some recording. They sent me out on the road doing some classical recording which I love. I got to do the Louisville Orchestra. They sent me down to the Village Gate when Barbra Streisand did her first recording for CBS-I think-then all of a sudden they give me my first sessions in the New York studio and it was cutting Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited! And I don't know what I'm doing! I'm skating on thin ice with this guy. I know enough about recording at this point that the singer cana't go over and stand next to the drums because he wants to. I mean I've got a big leakage problem, you know. And he wants to. So you do what he wants to do! And when you're new in the studio you definitely do what he wants to do because you're not sure of yourself! But somehow you get through it.

MF: Well that's a great sounding record on an original pressing.

RH: Well, it's all live. Al Kooper was on that date. Mike Bloomfield. Tom Wilson was the producer (Wilson also produced Frank Zappa at MGM)-it was fun.

MF: Everything was out of tune on that record-some idiot writer for CD Review dismissed the quality and importance of the record because of that.

RH: Well it was awfully out of tune, but…I'm getting excited about this now.

MF: Well sure! Did you realize at the time that you were making history?

RH: Oh no! I just looked at it as a session because everyone around there was just looking at it and saying, “What is this shit?” Of course, that's coming from a record company that's basically a pop company. So after Highway 61 Revisited-get this for luck, I love luck. Tom Wilson's bringing in these guys to do an audition. And in walks these two kids, Simon and Garfunkel. They're going to come in and do an audition. Two guys and a guitar-this is going to be great, I can't miss. This was at the 799 7th Avenue studio, which later turned into A&R Studios. A great studio, and they sold it! And they later moved to 49 E. 52nd Street. Terrible studios. So anyway, I do this audition for Simon and Garfunkel.

MF: Do you remember what song it was?

RH: Song? It was the whole album, man! The whole Wednesday Morning album was the audition.

MF: Did they know they were doing a whole album or did they think they were doing an audition?

RH: They didn't know. They were kids with their knees knocking through their pants. So we do this thing and I remember thinking I love it. I love these guys. I love the sound of their voices. I love the blend. Coming from a classical school, I heard classical influences. These guys are not run-of-the-mill and they're a pleasure to work with. So anyway, a couple of weeks later Tom Wilson is going to come in and add an electric rock track with some local musicians to try and make it commercial.

MF: Simon and Garfunkel had no idea this was happening, right?

RH: Absolutely. Paul was in England and Artie was off teaching somewhere. And we do these overdubs, and it's released, and Sounds of Silence because a huge hit, and all of a sudden it's “get these guys back!”

MF: Who did the arrangements of that stuff?

RH: In was all “head dates” in those days. You show them the song and they pretty much play what they feel. The guitar player was wayh out of tune, oh! It was awful. It was a 12-string electric and they are a mess to keep in tune. But now I'm making hit records, and at the studio that's a pop studio, and all of a sudden the studio becomes popular for rock and roll of all things! And before I know it I'm getting asked by outside clients and Columbia doesn't like that, but I did stuff for Kama Sutra. I did The Lovin' Spoonful's “Summer in the City” (Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful) album. That was a hit, and now I'm really hot and now the studio is hot. And it's such a fickle scene. All of a sudden everyone is saying “Let's try that new studio, Columbia, and let's get that young guy over there.” And artists started asking for me, too. And I like to think the success of that studio and Columbia signing some of those acts at that time was due to the sound we got. But you're talking to a guy that can't stand putting on his own records. They don't sound anything like the master tapes.

MF: Of course you heara the flaws and the mistakes…

RH: And it drives me crazy! I can't listen to too many pop records on the IRSes (Infinity IRS speakers Halee then owned). I'm more likely to listen to pop on the WATTs (Wilson Audio WATT/Puppys). Like a shaker-I thought I got a really nice sound on the shaker. And I get it sounding correct and it's placed hard left. And on the IRSes it's vague. But you throw it on the Wilsons and there it is! They image much better than the IRSes.

MF: Did you do any Dylan albums after Highway 61 Revisited?

RH: No. The thing about me is, I've got to like the people. They've got to be pleasant to work with.

MF: Dylan is notorious for not being easy to work with.

RH: Simon and Garfunkel on the other hand-I had a ball. Because now I'm out of this classical set routine: I'm in the studio, I can do what I want! I can put a mike out in the street if I want and I'm really having fun.

MF: They were open to experimentation?

RH: Absolutely! For example, they had great echo chambers at Columbia, but I didn't like the speakers they had in there-the sound. So I said “Let's go in the echo chamber and try to do some vocals in there.” Well, you know the background vocals on “The Only Living Boy in New York” on the Bridge Over Troubled Water LP? The “aah aah ah ahs?” That was done in one of the echo chambers and I think it's an interesting sound.

Plus, Dolby. I don't like Dolby (noise reduction), but Dolby can do some interesting things sonically. You can record in Dolby to push the top end, but don't resolve it, which we also did on those voices. IT can give you a kind of snap you can't get with an equalizer on some things.

We did “Bye Bye Love” and Paul said one day “Why don't we do it live, and the audience can be our drum.” He said “Let's not use a drum”-that's where he was coming from. Always looking for something different and interesting. So we go out and start doing live performances and we find we're not really making it-somebody's always making mistakes-we're not going to get this. Sometimes the audience is good, but they're not, or they're good and audience can't keep time. So I say, let's go in the studio and get it right, and let's go out and overdub the audience!

MF: Did they have an aesthetic problem with that?

RH: Not really, just that it would be hard to do…then the aesthetic thing did come up, you know. And I said you could tell the audience what we're up to, up front.

MF: It's funny-when the Milli Vanilli controversy occurred, a writer in The New York Times said it was no different from Simon and Garfunkel's Sounds of Silence overdubs.

RH: That's ridiculous! So we did it. I overdubbed the audience applauding on (beats) two and four to the track. We went out to different locations because we weanted to mix in a few audiences. And they would fall out of rhythm occasionally, so we had to wild track (a track recorded on a different tape machine and not synched up to the original) and in those days you couldn't sample, so I had four two-track machines wild tracked, so you could grab stuff from each. Now I'm in my glory, thinking more about experimenting than sound.

MF: Where did the deep “thunk” on “Cecilia” come from?

RH: We recorded that basic track on a Sony home machine in Paul's living room and then we dumped that onto a multitrack in the studio. And that thunk is just a big bass drum.

MF: The piano on “Bridge Over Troubled Water”-the sound of that piano is spectacular. Do you remember how you got that? In fact, where did the form for the sound to that song as a whole come from? How much of it was you, how much of it was Paul?

RH: It was both of us.

MF: And that's why the two of you have worked together all these years? Because you have a symbiotic relationship?

RH: The basic track was just a piano with Larry Knechtel in that huge CBS studio in Los Angeles, and the piano was out in the middle of the room with mikes back in a classical configuration instead of right over the keys.

MF: And the wet, fat drum sound?

RH: Just experimenting. The snare compressed to some degree-the kit was out in the hallway-anyplace but in the studio, which gave it that nice big sound like an explosion.

MF: Most of the manipulation done today is not organic like that-it's electronic.

RH: Sound, to me, means a symphony orchestra in a wonderful space-all acoustic with air, ambience, deep soundstaging. That's how I'm prejudiced. But in the pop thing, it's more fun, feel, and experimenting. But I'm patronizing in the sense that it will never sound like, or have the weight of say, the Berlin Philharmonic playing in a wonderful space.

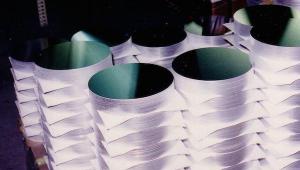

We did a lot of experimenting in audio with respect to what they have today with AMS and Quantec reverb units, DDL (digital delay lines), the new Harmonizer H 3000 which is a hell of a machine that can do just about anything. All these sampling devices-like on Graceland we used Paul's Synclavier-amazing. I brought in my snare drum, we sampled it and put it where we wanted it. But in some of those Simon and Garfunkel records it really came off like the sounds they're doing today, only it was all done flying in, fast delays using tape machines flanging, and I could sight instances where the sounds we got are the sounds of those machines today, only better because they were analog and sound better.

For example on “Save The Life Of My Child” that big choral sound, I flanged the chambers using tapae machines running slightly off speed from each other. You could create hugh sounds that way. What am I doing basically? I'm using a really fast DDL. “At The Zoo,” I thought it would be really neat to give a featured scraper some character, so we flanged the echo chamber. We took the output of the mono echo chamber to two machines and oscillated one up and down in speed. Today they're into that kind of manipulation, but we did it then without electronic processing.

The best record I ever made technically-and it still satisfies me sonically and every way, and I don't care what anybody says-was “The Boxer.” Unbelievable-I love to talk about that record-well, we made it, Paul and I. It's insane, the sounds that are on there. You talk about AMS reverbs? That sound is all over it, but done by opening and closing echo chambers by feel and hand-machines can't do it. There's a bass harmonica on that. It was an eight-track recording.

MF: One? Not two synched up?

RH: That's what I ended up having to create to fit all of those voices on there. I needed 16-tracks. I had to figure out a way to copy all of the first eight tracks onto the second for headphone feed. I figured it out. So we filled up the first eight tracks really quickly with music. Then I came up with the idea of making a big choral thing at the end. Artie says “Yea, it would be neat to go up to the chapel at Columbia University and do it” because Artie went to Columbia. Now we're talking about taking an eight-track with Dolby, remote, which has never been done before, and now CBS is saying “is this really necessary?”

MF: And from a studio that was putting microphones in set places!

RH: Exactly. And here we were adding voices, a big tuba, and a piccolo trumpet playing the melody over a previously recorded Nashville steel guitar to make it a very interesting sound. And here's that church sound, it's not in stereo, we had to do it in mono because we had a track problem. Then we go out and overdub Paul and Artie doing “lie la lie, lie la lie…”

MF: And then there's that big drum “kishhhhhh.”

RH: Well that was done in the elevator shaft at Columbia! So we go to the church, andd their voices with Dolby, and now we're out of tracks…Then we were going to do strings, so we decide to record it onto a two-track and wild track it into the final mix.

MF: You had to use a variable pitch control to keep it in synch with the rest?

RH: That's what I did. Not only that, there's a Dobro lick in it, that's a wild track. It took a long time [to mix and cut], but from a technical standpoint, man! Starting with the basic track done in Nashville with Fred Carter and Paul, just Travis picking-unbelievable! Then that great drummer Buddy Harmon added shaker. Then we built it up, adding the second eight. And I'm going to mix and I'm ending up with two eight-track Ampexes and two machines of wild tracks-“please God, make them run in synch” because as it gets hot, they drift. But it worked. It worked on The Byrds stuff too, because I took that to Hollywood to this producer Gary Usher and he saw it and went out of his mind!

But there's a follow up to this that's really going to kill you! Everybody else is getting 16 tracks (machines) but Columbia! And I have to go through all this hassle because I don't have 16 tracks! But I understand because they have a lot of studios and for them to gear up to 16 tracks would be very expensive.

So we go to the mix, and Artie is off doing his movie-which is the demise of Simon and Garfunkel and Paul and I are in the studio mixing, my daughter is born the night before, I'm up all day and night and I'm in great shape. It started to drift out after 12 hours, so I had to offset them and splice the big ending and the strings, which were completely wild. If that had to be mixed today, nobody could do it, guaranteed-and that includes me!

Please go to part 2 of the interview by clicking here.

- Log in or register to post comments

Checking your SASSA grant status is more than just staying informed—it’s a vital step in protecting your personal information. By regularly confirming your application details, you can help prevent unauthorized changes and detect identity fraud early. If anything appears incorrect, it can be reported immediately. This process ensures that grants are delivered safely and only to eligible beneficiaries. People can visit the SASSA status check portal to confirm the status of their SRD and social grants. It’s a smart way to safeguard your support and keep the system fair for everyone.

I follow UK49s daily, and it’s surprising how often repeat numbers pop up. I found a website that not only posts the Lunchtime and Teatime results quickly but also shows them with colored balls, which makes it visually easier to compare — super helpful!

RUNT Por Placa es una herramienta útil que permite a los ciudadanos consultar la información vehicular registrada en el sistema RUNT utilizando únicamente la placa del vehículo.