Analog Corner #124-All Quiet on the Vinyl Front

Talk to vinyl fanatics about record-cleaning fluids? I’d rather discuss with Rummy the wisdom of invading Iraq, or debate with drug czar John Walters the efficacy of the so-called “war on drugs.” I’d rather talk to a wall. But here I am talking about them, having spent the better part of the summer swimming in the stuff. So many claims are made about how well they clean, and even about how they sound, that I decided a careful survey was in order. Remind me never to do it again.

What prompted this survey was the unearthing of Myles Astor’s article on the subject, published in an issue of the long-defunct magazine Sounds Like . . .. Although I don’t agree with some of Astor’s conclusions, the article is excellent, covering vinyl chemistry and fluid ingredients in admirable detail. I’ll spare you the chemistry, but here’s one of Astor’s conclusions: “[W]hile vinyl appears to be a solid, at the molecular level, it’s porous enough to allow chemical exchanges over time between the record’s surface and its interior.”

All vinyl compounds used for pressing LPs contain, among other ingredients, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyvinyl acetate (PVA), the latter a softer material used as a plasticizer to keep the disc from becoming too brittle. Other ingredients often added to make the final vinyl biscuit include antistatic compounds, as well as coloring agents (carbon-black or dye) to give the naturally clear plastic its usual black color.

While a stylus’s downward tracking force is small—only couple of grams—its footprint is so tiny that the pressure per square inch that it exerts on the groove walls is enormous. Add the buildup of heat due to friction and you can understand why a tiny ridge in a microgroove pressed into a brittle material might crack and break. Hence the plasticizer.

In fact, one cause of the pops and clicks that mysteriously appear on pristine records after only one or two playings is due to impurities in the vinyl compound that break off or pop out under this pressure. (One of the claims made for the LAST preservative, once very popular, was that it bound those impurities to the vinyl’s polymer chain at the molecular level and thus prevented those pops and clicks from occurring.)

Water and isopropyl alcohol can leach plasticizers from vinyl compounds, making them more brittle, but, as Astor pointed out in his piece, in order for that to happen the fluid must be in contact with the record for at least an hour. If you apply fluid and vacuum it off within 30 seconds or a minute, can any plasticizer possibly be leached out? It’s unlikely, unless a residue is left on the record surface. One way to prevent that from occurring is to follow the cleaning with a rinse of distilled water, then another vacuuming. More about water shortly.

Another variable to be reckoned with is mold-release compound—a lubricant added to the vinyl during manufacture or sprayed on the stamper itself to ease the removal of the newly pressed record, and which has a tendency to “cloud” and soften the sound.(NOT TRUE-Ed 2020).

As for the best record-cleaning regimen I know of, regardless of what fluid(s) and applicators you use, see Michael Wayne’s fanatically meticulous article . Even I don’t have the time, energy, or desire to follow Wayne’s advice to the letter, but I do make use of his insights in caring for my records. I’m sure you’ll find his advice useful as you formulate or update your own.

What we’re trying to remove from the grooves with all this cleaning is dust, fingerprints, mold-release compound, Special Sauce, cigarette ash—and that’s from some brand-new records I’ve cleaned lately. In addition to any or all of that, a used record might have cannabis resin, mucus, semen, blood, urine, sweat, rat droppings, cooking oil, lighter fluid, dishwashing detergent, and—the LP was stored in a wet basement—organic mold. You never can tell what’s on a garage-sale record—people have handled them who were doing G–d knows what at the time. And because records retain static charges that attract all kinds of crap, anything in the world might be lurking in the grooves of your used LPs.

Water, water, everywhere

H. Duane Goldman, a PhD chemist who’s also known as “The Disc Doctor” (Goldman recently retired and sold his business to Acoustic Sounds), claims that alcohol is used in record-cleaning fluids because of a “lone engineer at the British Museum who was on record as having stated that, following cleaning with methanol-water, he ‘liked the look of the disc.’ ” Goldman went on to tell me that Thomas Edison himself used methanol to clean his Diamond Discs, “to avoid wetting the spindle hole or edges of the disc, as these discs are a layer of phenolic resin over a filler that could absorb water, resulting in swelling and/or cracking of the surface.”

Quality counts

Water can be purified by deionization or distillation. You can buy steam-distilled water at the supermarket, and that’s better than tap water, but super-pure, deionized, reverse-osmosis–filtered water is the best kind to use for cleaning records. If you plan on saving money by buying concentrated cleaning fluid and diluting it yourself, visit your local college’s chemistry lab and try to grub some, or buy a reverse-osmosis filter for $135 and make your own. (I’m buying a reverse osmosis filtration system from FilterdirectOtherwise, buy a ready-to-use fluid and hope the manufacturer has used distilled water that’s better than supermarket grade.

Some manufacturers are quite open about what they use in their fluids; others won’t say. Record Research Labs, Audiotop, and L’Art Du Son’s are teetotalers. Of the manufacturers who use alcohol, most use isopropyl, of which there are various grades of purity. Audio Intelligent for instance, uses laboratory-grade isopropyl for its Record Cleaning Formula.

I didn’t talk to every manufacturer, but no one with whom I did speak specified the surfactants they used. Goldman says he uses a “carefully tweaked blend of ionic surfactants” in his standard fluid, and “non-ionic” in his Quick Wash. Audio Intelligent’s Paul Frumkin says that, along with using high-quality ingredients, the key to an effective cleaning solution is the proportion of those ingredients.

Now what do I do?

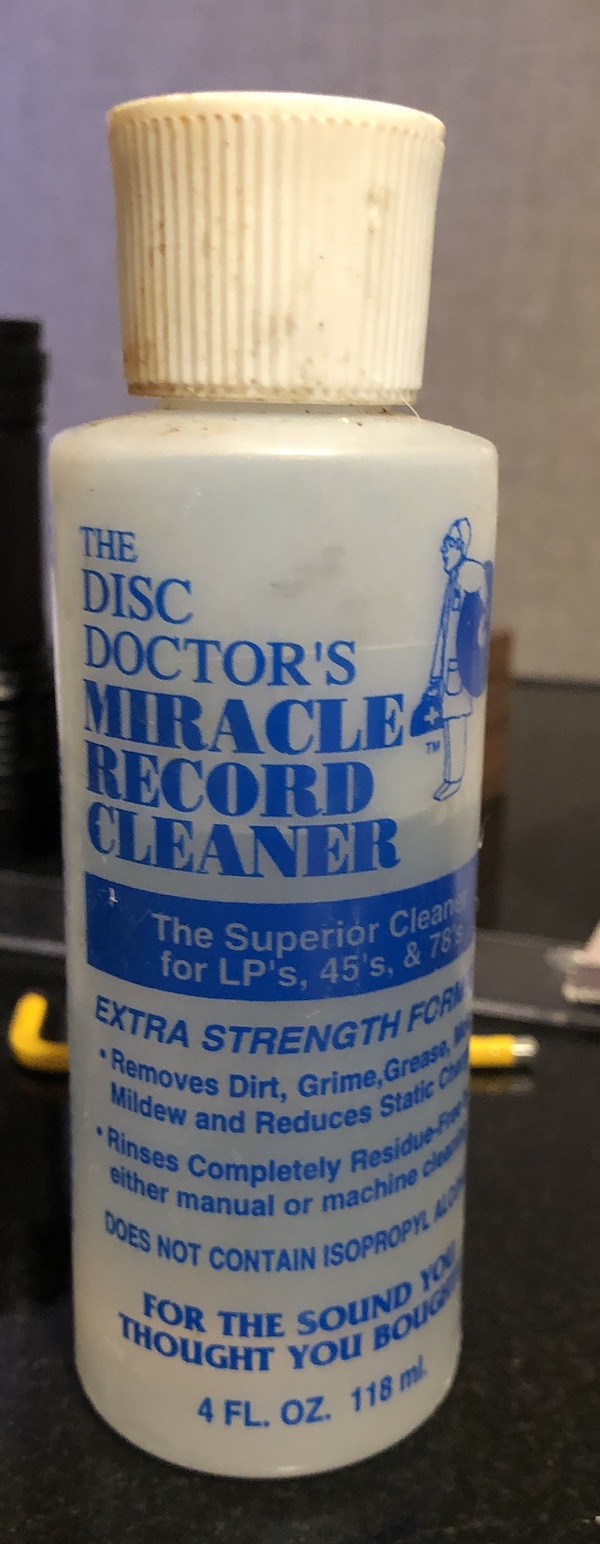

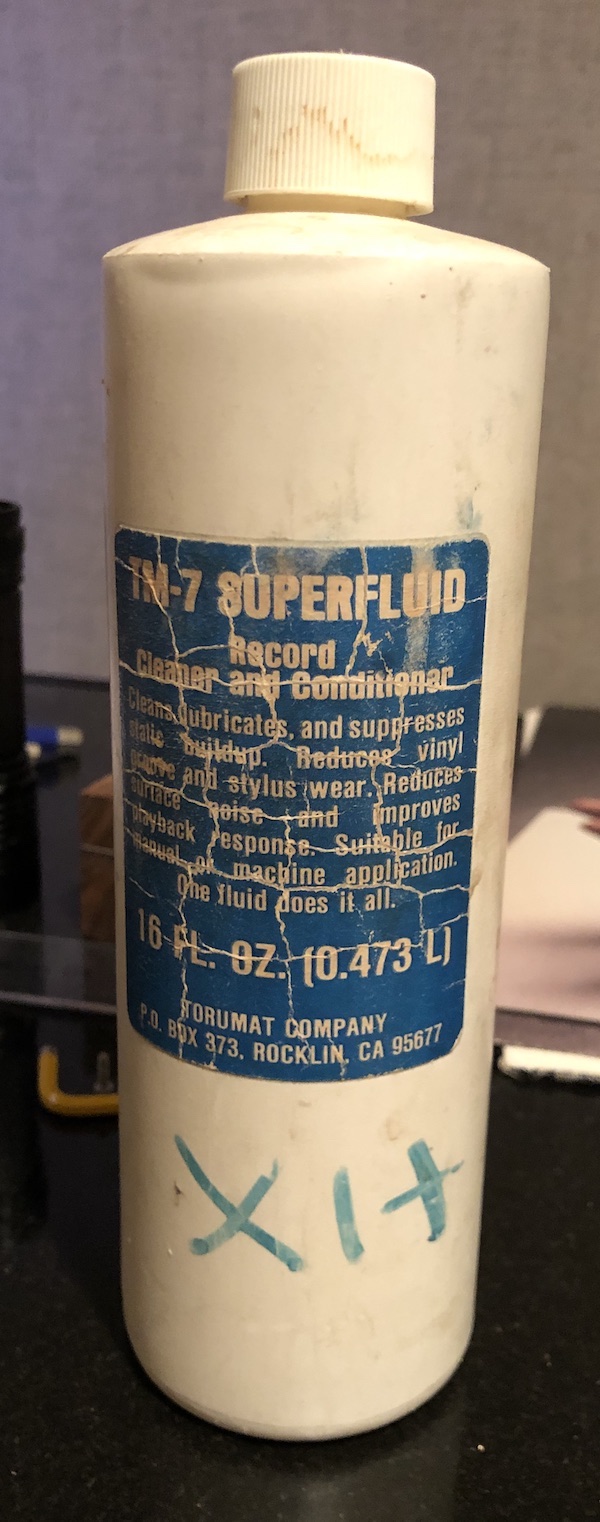

There I sat, staring at fluids from Audio Intelligent, Disc Doctor, Record Research Labs, Audiotop, L’Art du Son, VPI, Nitty Gritty, Bugtussel, LAST, Lyra, a guy named Brotman, and some old Torumat, vintage 1986, which I bought when I lived in Los Angeles and can’t bring myself to pour down the drain. But you should know that the shelf life of these products is finite, so don’t stock up. Some last longer than others; a year or so is a safe bet. With most of them, if you see sediment at the bottom of the bottle, it’s time to replace.

The mesmerizing singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens had United’s Nashville pressing plant send me five test pressings of his latest double LP, Illinoise (Asthmatic Kitty), to get my approval before the press run. I felt honored. I played an uncleaned side, then cleaned each side of each set’s first disc with a different fluid, for a total of 10 fluids. Then I listened.

What did that prove? Scientifically, nothing—there’s no way to scientifically compare these fluids. Once you clean a record with one fluid, cleaning it with another doesn’t allow you to fairly compare the two—the second fluid tested benefits from an already clean record. You could reverse the process on the other side, but each side of a record is different. And you know what? Press 10 copies of a record from the same stamper and each can sound slightly different. Still, I cleaned and listened—I wanted to hear the album a few times anyway.

I wasn’t listening to hear which record cleaner “sounded better.” I think anyone who says that fluids “sound” different is delusional. If you put any cleaning fluid on a record and vacuum it all off, the only sonic difference can be the absence of dirt or residue, not the addition of a “sonic signature” from a nonexistent substance. That can be significant if a particular fluid removes crud and noise no other fluid managed to do, but it doesn’t mean you’re “hearing” the fluid. The only time you’ll “hear” a cleaning fluid is when you haven’t removed all of it, or when it’s designed to leave behind a residue, such as a lubricant. If you think otherwise, please write and tell me how a piece of vinyl’s intrinsic sound can be changed by pouring fluid on it, scrubbing it, then sucking all the fluid off.

I played side 1 of Sufjan Stevens’ Illinoise, then cleaned it and played it again. There was definitely greater focus and clarity, probably because most of the dirt and mold-release compound had been removed. Cleaning it again, with another fluid, made no difference that I could hear. Nor did playing the 10 cleaned sides back to back reveal any sonic differences. All 10 sides had occasional pops and ticks that no amount of follow-up cleaning could eliminate.

Do all of these fluids remove mold-release compound with equal effectiveness? I don’t know—I don’t have an electron microscope. But I used each fluid to clean a different brand-new LP that I played once before cleaning, and every disc sounded better after being cleaned: quieter and better focused. Machine-cleaning new records is as important as cleaning old ones.

I applied all of these fluids, as directed, to many other records over a period of two months, using inexpensive nylon brushes to avoid cross-contamination whenever a cleaning fluid did not come with its own applicator. None of them removed the white “spider webs” that leach onto record surfaces from polyethylene inner sleeves such as the ones Decca/London/Deram used in the 1960s (put those Moody Blues LPs into new sleeves!). Otherwise, all of them left cosmetically attractive surfaces, though some did a better job of removing mold, as well as those stubborn fingerprints that seem to be applied with white paint. If a fluid couldn’t eradicate a fingerprint, or some other physical or sonic blemish that looked or sounded as if it might be removable, I tried another fluid.

When I began this survey, I planned to rate each fluid in terms of its spreadability, odor, ease of use, cost, packaging, stylus residue after play, etc. But when I smelled the first one and almost passed out, I canceled the stink test. You won’t be deliberately smelling this stuff, so why should I? I killed off enough brain cells during the 1960s (and 1970s, and 1980s, and . . . ).

I divided the cleaners into two categories: Everyday and Heavy-Duty. I will report on the Heavy-Duty cleaners next month. All of the Everyday fluids did satisfactory jobs of cleaning new records, as well as used ones that were moderately dusty and marred only by oily fingerprints. The differences were in packaging, ease of use, and price.

Alcohol-free everyday record cleaners

I don’t buy the claims that alcohol damages records. Yes, the wrong kind of alcohol can damage an LP, just as the wrong fluid of any type can. That said, all four of these proved that dusty, dirty records can be cleaned and, as best I could determine, mold-release compound be removed—all without alcohol. Audiotop’s Vinyl1 is specifically designed to remove mold-release compound, along with the usual dirt and grime.

Audiotop doesn’t divulge Vinyl1’s proprietary ingredients but describes the solution as a “special detergent” made of a “highly purified (99.999%) non-specified substance, Aqua Purificata (repeatedly distilled and purified) and special tensides.” Because the product itself is described as a “detergent” and not as containing a detergent, I assume the “non-specified substance” is not alcohol, though Vinyl1 does smell like alcohol.

At $157/quart, Vinyl1 was easily the most expensive record cleaner of the 10 I tested, so use judiciously. Audiotop doesn’t make this easy to do so: the fluid comes in an open-mouth container not suitable for direct application to vinyl. For $157/quart, a smaller applicator bottle should be included.

Vinyl1 spread easily and worked as promised. New records sounded more transparent and detailed after being cleaned with Vinyl1—what you should expect from any cleaner that’s claimed to remove mold-release compound. Vinyl1 worked well, but the price is steep, even taking into account that you’re paying for water shipped from Switzerland.

Record Research Labs’ premixed Super Wash uses quadruple-distilled water and features “non-toxic, natural de-greasers and dirt solvents.” The latest formulation, “ten times more powerful” than the preceding one, doesn’t seem to use a wetting agent—it beads up on the record surface and is difficult to spread, even using Disc Doctor’s applicator pad, which is the most effective in my arsenal. If you’re not careful, the beads will flow right off the record; more will end up on your floor than in the grooves. Even if you’re as careful as I was once I saw how Super Wash behaved, going slowly to try to get the liquid to spread evenly, more of it appears to sit atop the disc surface than migrates into the grooves. Still, enough apparently manages to get down where it belongs—Super Wash did a good job of cleaning new and moderately dusty old records and left no residue on the stylus. At $100/gallon, the fluid is expensive: again, you’re paying to ship water. On the other hand, quadruple-distilled water is better than you’re likely to get without investing in your own reverse-osmosis rig.

L’Art du Son’s concentrate comes in a tinted glass bottle—the company says it’s light-sensitive and should be stored in the dark. It also separates over time and needs to be shaken before use—so don’t pour it into the well of a pump-equipped vacuum-cleaning machine. It spread easily and was effective at cleaning new and moderately dusty used LPs. The label has a “best if used before” date—something all makers of cleaning fluids should include. At $45 for a gallon of finished fluid, L’Art du Son costs less than half of what Record Research’s Super Wash costs, though for best results you should use steam-distilled water that’s better than supermarket grade. That’s what I used (my reverse-osmosis filter has yet to arrive).

Lyra’s VPT(C) concentrate is so new that its page on Lyra’s website it is still “under construction.” According to a UK site that sells the stuff, VPT(C) was developed by Torumat’s Toru “Toy” Shigekawa, Shiro Suzuki, and Lyra cartridge builder Yoshinori Mishima. The fluid is said to clean as well as lubricate, which means that, like the Torumat fluid, it must leave a residue of something in the grooves. I can understand why a cartridge maker would want to lubricate the grooves to reduce stylus and groove wear, but it seems to me that cleaning and lubricating are different tasks best accomplished by separate products. VPT(C) contains a “proprietary surfactant formula,” but the lubricant isn’t specified.

I listened to a new record rich in high-frequency transient information before and after cleaning with VPT(C), to check on the lubricant’s sonic effects, if any. (I’d first cleaned the LP with another fluid to remove mold-release compound.) I thought I heard a slight overall “smoothing” of the presentation and a damping down of air—nothing dramatic, but definitely noticeable. I need to do more listening before drawing any final conclusions about Lyra VPT(C). And I need to find out what’s in it—particularly the lubricant.

Everyday fluids containing alcohol

Nitty Gritty Pure 2 contains a degreaser, a static neutralizer, a mild detergent-surfactant, and an unspecified alcohol. It was as effective cleaning regular dirt and greasy fingerprints from records as any of the fluids I tried. It costs $39.95 per half gallon or $67.95/gallon.

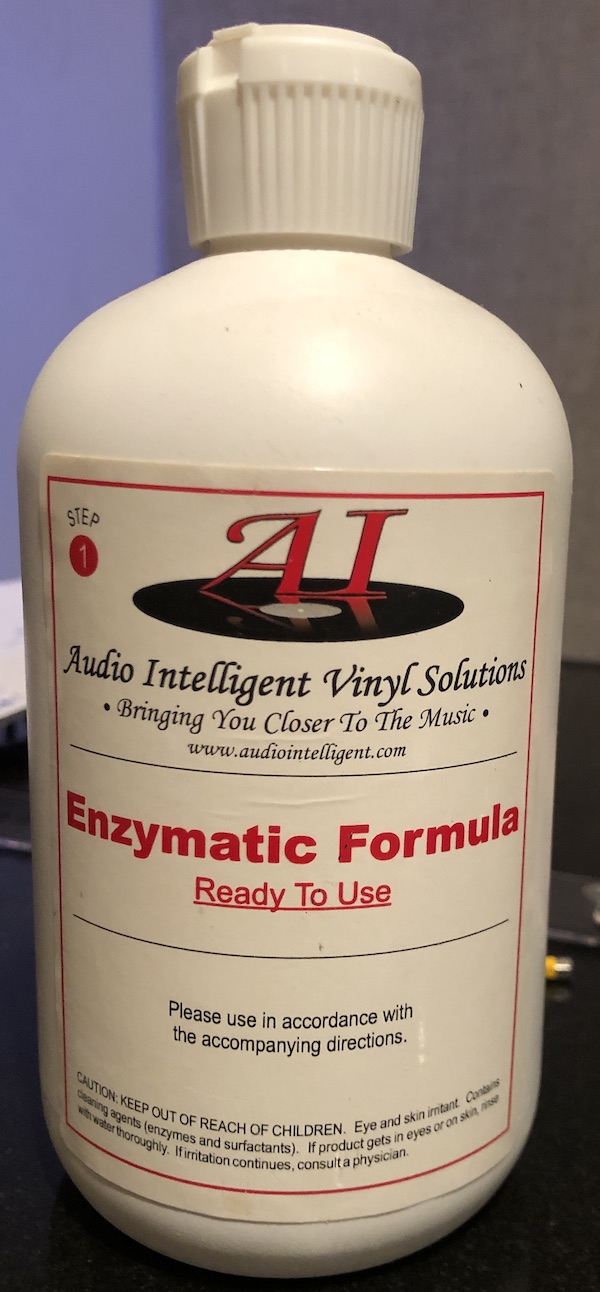

Audio Intelligent’s Record Cleaner Formula uses laboratory-grade isopropyl alcohol and a detergent-surfactant. It’s meant to be used in conjunction with Audio Intelligent’s Enzymatic Cleaner (see next month’s column) and is available as a concentrate (a $14 bottle makes a quart, a $25 bottle makes a half gallon) or ready to use ($20/quart, made with “Ultra-Pure,” four-stage, reverse-osmosis water).

My sample of VPI’s LP-cleaning fluid is ancient and Harry Weisfeld didn’t send a new sample in time for this survey.

Next time: Heavy Duty Solutions, cleaning and storing tips, conclusions, glaring omissions.

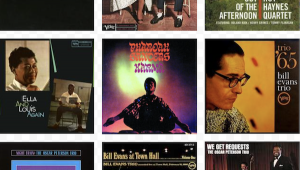

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Esquivel, Exploring New Sounds in Stereo, RCA/Speakers Corner 180gm LP

2) Duke Ellington, Piano in the Foreground, Columbia/Classic 200gm Quiex SV-P LP

3) Various, Man of the World: Reflections on Peter Green, Morada Music/Audio Fidelity 180gm LPs (2)

4) Thelonious Monk Quartet, Misterioso, Riverside/Analogue Productions 180gm, 45rpm LPs (2)

5) Daniel Lanois, Belladonna, Anti/Epitaph 180gm LP

6) Patricia Barber, Nightclub, Blue Note/Mobile Fidelity 180gm, 45rpm LPs (2)

7) Matt Sweeney & Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Superwolf, Palace/Drag City 120gm LP

8) Amadou & Mariam, Dimanche a Bamako, Nonesuch CD

9) Sufjan Stevens, Illinoise, Asthmatic Kitty LPs (2)

10) Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, Going Back to Acoustic, Pure Pleasure/Isobel 180gm LP