Billy Byers—Impressions of Duke Ellington —Mercury PPS 6028—The Records You Didn’t Know You Needed #10

From 1960 to 1965 Byers worked as assistant to Quincy Jones who was first music director and then vice president of Mercury Records. It was a job that provided an income that was undoubtedly more secure than one provided by freelance arranging. Byers, during his tenure at Mercury devoted most of his time to behind the scenes production work, but in December 1961 and January 1962, he did record Impressions of Duke Ellington , an album of his arrangements of ten Ellington and Strayhorn compositions. Probably, Quincy Jones conceived of the project and convinced the Mercury business people to fund it as the liner notes state that he “supervised” the session and “selected” Byers.

In 1962, Mercury Records was a successful independent record company selling almost all genres of music from country to classical. Its Living Presence classical recordings, engineered by Robert Fine, have become legendary in audiophile circles for sound quality and have been extensively discussed and documented on Analog Planet and elsewhere. The Living Presence LPs, profitable and prestigious, proved that sound quality could be a selling point and Mercury, in 1960, began its Perfect Presence Sound series as a pop music counterpart. Robert Fine and his Fine Recording studio were contracted to record many of the LPs and the equipment and techniques developed while recording the Living Presence albums were utilized to provide a similar, though more flamboyant, sonic experience.

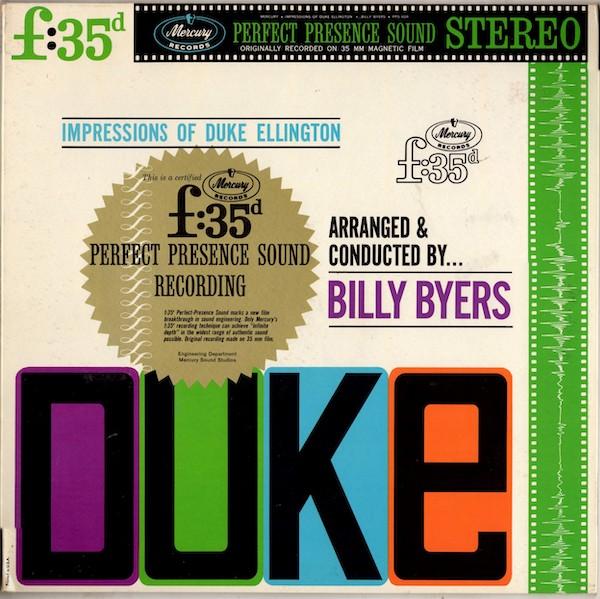

In 1961, Fine in his determined pursuit of the most accurate sound reproduction, began using 35-millimeter film instead of audio tape for recording both the Living Presence and Perfect Presence series. Tom Fine, the son of Robert, was quoted in a 2012 Stereophile article, “Dad thought the film stuff sounded markedly better. It’s lower noise, lower print-through, its wider tracks, and a slightly faster speed so, theoretically, a slightly better dynamic range-and definitely a lower noise floor.” Fourteen Perfect Presence albums, including Impressions of Duke Ellington were recorded on film. The Mercury advertising department could sling a hyperbole with the best of them and the front covers were emblazoned with a large gold seal certifying an “f:35d” recording and stating that “Perfect-Presence Sound marks a new film breakthrough in sound engineering. Only Mercury’s f:35d recording technique can achieve ‘infinite depth’ in the widest range of authentic sound possible.” They probably considered promising all this Perfect-Presence Sound “forever” but decided that would be going too far.

The Perfect Presence series was aimed at the burgeoning stereo/hi-fi market, which was beginning to cross over from hobbyists and classical music buffs to mainstream, middle class America. Unfortunately, but probably accurately, Mercury’s marketing department concluded that the non-classical market for records to show off your new stereo hi-fi system, was not made up of buyers of jazz or sophisticated pop and the Perfect Presence Sound series consisted of approximately 30 LPs, limited almost entirely to justly forgotten mood music and exotica. Seven jazz or semi jazz albums were in the series and all except Impressions of Duke Ellington are gimmicky in instrumentation or the selection of tunes. That Byers got to record a jazz big band album with only small concessions to the marketplace was probably entirely due to the support of Quincy Jones.

The band Byers assembled to record Impressions was a mixture of New York studio pros and jazz musicians that included Clark Terry, Joe Newman, Jimmy Cleveland, Melba Liston, Eric Dixon, Milt Hinton, Patti Bown, Osie Johnson and Eddie Costa. To the usual jazz big band instrumentation, Byers added four French horns and two percussionists playing marimba, tympani, bongos and all the various, miscellaneous etc.

Of the musicians that played on the album, only one—Clark Terry—was ever a member of the Ellington Orchestra. One of the common clichés, almost impossible to avoid, when writing about Ellington is that “he wrote for the musicians in the band” and like many clichés there’s a lot of truth contained in it. There are thousands of versions of Ellington compositions and some of them are masterpieces but no band, even ones that played Duke’s own charts, ever duplicated the sound of the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Byers had too much intelligence and respect for Ellington to record a “Tribute to Duke” type album using non-Ellingtonians playing sound-alike arrangements of Duke’s music.

Instead, the arrangements Byers wrote for Impressions are personal, sometimes eccentric, modernized, 1962 versions of the Ellington and Strayhorn compositions. They are not like the straight ahead jazz big band charts he wrote for Count Basie, Jimmy Smith and so many others. The Swing Era was two decades in the past and now, at the beginning of the “swinging sixties,” “swinging” had a whole new meaning. There’s plenty of complexity, tricky time changes, unusual reharmonizations and swinging, but there’s also bits of goofy humor, exotica, kitsch and lots of flashy whizzbangery to show off the new stereo. I strongly suspect Quincy Jones told Byers something like, “This is going to be in the Perfect Presence series not the 36000 jazz series. Jazz is OK but don’t forget the squares.”