Clap Hands Hear Comes Classic Records Jazz! Part 1

Spend a few days watching how they make records late twentieth century style and you'll understand why hardly anyone makes them anymore. You'll also appreciate why the good ones cost what they do.

When Classic Records' Ying Tan and Mike Hobson invited me out to watch how they're mastering and pressing modern plastic biscuits, I dropped what I was doing -listening to records of course-and flew out to L.A. post haste.

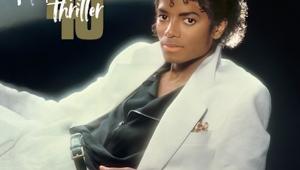

Why the rush? Having served up a dozen or so classical vinyl titles from the RCA "Living Stereo" catalogue, they were about to perform the same valuable service for jazz lovers by re-mastering some classic Verve jazz titles- including audiophile favorite Ella Fitzgerald's Clap Hands Here Comes Charlie - and I wanted to be there to watch.

American Airlines wanted $1300 round trip for the privilege of instant flight- and you think high end audio is a rip-off? Fortunately Tower only wanted $300.00 back and forth. Tower? Virgin Air is connected to the record label and the stores, but Tower isn't- unless El Al bought the record chain from Russ Solomon while no one was looking.

El Al, an outfit which knows how to fly, owns Tower and you'll have a great flight unless your name is Mohammed. Then you'd better not be carrying any suspicious packages, otherwise you'll end up like the Mo' on my flight home: "Will Mr. Mohammed (whatever it was) please come to the front of the plane to claim a package? If not, it will be be removed from the plane and left at the gate". Those folks don't mess around. Neither do the Classic Records folks.

When Hobson and Tan launched their label at the Winter '94 C.E.S., nay-sayers-and there were quite a few- didn't think they could pull off their ambitious twelve LP release schedule and do it with the requisite high quality and consistency demanded by the undertaking. After all, it was argued, these guys were amateurs at the record production game-and look what the Cheskys had done with their go round: middling mastering, variable pressing quality- not what audiophiles were demanding- though some of their releases were and are quite good.

A year has passed: Tan and Hobson have clearly brought their dream to fruition: the vinyl "Living Stereo" catalogue lives. What's more, they're making money and having fun doing it. Seeing a 12X12 "Living Stereo" copy of Gaite Parisienne (LSC-1817) or Also Sprach Zarathustra (LSC-1806) is a kick even for those of us lucky enough to own or have owned originals.

I have an original 1806, bought off a guy from Florida advertising "shaded dogs" in Goldmine back in 1986. "I'll give it to you for ten bucks- there's something wrong with the beginning. Sounds like wind howling". The pipe organ of course. Now that disc is worth hundreds-even with the Classic reissue.

I had an original Gaite Parisienne which an acquaintance had picked up at a flea market in Birmingham Alabama for fifty cents, but when someone offered $800 I couldn't refuse. The new Classic Records issues with their pristine surfaced180 gram vinyl discs, rich looking digitally re-mastered covers (ironic isn't it) and "shaded dog" labels -priced under $30.00 are brand new treasures sure to become collector's items in their own time.

Despite the impeccable packaging and high quality production and sound, the series remains controversial. Some audiophiles don't like

what they hear compared to original pressings: "too modern", "too bright", "too antiseptic", "too solid state". There's a great deal of sniping and second guessing. "Shoulda used tubes", "shoulda used Doug Sax", shoulda, shoulda, shoulda. Bunch of ingrates if you axe me.

What should Classic Records' goal be? To duplicate the sound of original pressings, most of which have been compressed, rolled off at the frequency extremes and summed to mono in the bass? Or should the company try to give the end user-or better of worse-the sound of the master tape?

And exactly what isthe sound of the master tape? What does that really mean? The sound of the master tape played back on what equipment? Or should they have EQ'ed and altered the tapes to sound "good" on a "reference" system circa 1994? Maybe, but that begs the question: sounds good to whom? If you play the same record on a hundred different systems, you've heard a hundred different sounding records.

Comin' Into Los Angeles....

All these and many other questions danced through my head as the 747 touched down at LAX last fall. Fresh in my mind's ear was a listening session the previous evening during which I compared Classic's stupendous Pictures At An Exhibition with a 23S "shaded dog" and a later "white dog" pressing, both of which I'd acquired at garage sales- the stuff's out there if you have the time and inclination to go looking.

To my ears, the Classic reissue wins on most counts: it's quieter, more dynamic-explosive in fact-better focused, with outstanding image specificity, inner detail, and transparency. While this reissue- and most of the other Classics I've heard, are brighter than the originals, they are still "sweet" sounding and free of the grain and texture most of us associate with an increase in high frequency energy. The "shaded dog", outstanding as it is, sounds somewhat clouded over with a milky texture- as if a thin scrim had been placed in front of the orchestra.

The originals marginally bettered the reissue in two areas: portrayal of hall ambience and the golden glow of the brass which comes across somewhat thinner and less burnished compared to the "dogs" and to live music.

The diminished ambience might be attributable to a high frequency loss inevitable on a tape, which is almost forty years old. And the "golden glow" could very well be a cutter head resonance, and in any case comes at the cost of many other sonic problems inherent in a lacquer cut from a signal which has been compressed, equalized and summed to mono in the bass.

While all RCA original LPs were mastered from production tapes (in the case of 3 track masters, they were mixed down to two tracks) Classic used original master tapes- even three trackers- using a three track head stack to play them back and cut lacquer in real time.

Look, some audio obsessives will pick over these dog reissues like crows on road kill, but you can count me out: good luck finding originals, and good luck finding them clean and for less than a day's pay-or a week's if you write for a living. If these Classic reissues were genuinely inferior in every way, I'd be one of the second guessers, but they'rebetter in most ways (with the exception of LSC-1806 which really does suffer compared to an original, but good luck finding that for less than $300.00).

Bernie Grundman Mastering 's Sunset Boulevard facility in Hollywood is a small busy place-two floors of constant motion-with tapes coming in and lacquers and 1630 masters going out. The raw materials of your favorite releases are stacked on shelves and in the hallways, the walls of which are filled with gold records and pictures of Bernie with his mostly famous clientele.

Grundman's first floor mastering suite is surprisingly small- and even more crowded with tapes than the hallway and front office areas. Compared to some other newer rooms, it is singularly unimpressive. Greg Calbi who recently moved from Sterling Sound to Masterdisk in New York showed me his new room: its big, open, and set up like an audiophile listening room with ProAc Response 4 loudspeakers driven by Audio Research tube gear. The "front end" is of course mostly pro stuff, but there isn't an audiophile I know who wouldn't find the sound in the room impressive. (Calbi is back at Sterling-ed. 2004)

Grundman's room, on the other hand, is more typical of the "nuts and bolts" kind of suite you'd find in mastering houses during the late seventies through the mid eighties: the Tannoy monitors are behind black grille cloth and built into a wall fairly close to the listening position; the solid state Crown DC 300 amps hidden from sight. Grundman uses a custom built board and it looks clunky, home made and low tech compared to some of the slick, gazillion button blinking light jobs you see advertised in EQ or Mix magazine.

But Grundman, an industry veteran (27 years in the biz) who worked for Lester Koenig at Contemporary during the golden age of vinyl, and later ran A&M's mastering facility before going off on his own, is a no show all tell kind of guy. He retains an impressive list of clients because of the quality of his work and the quality of his set up, not the surface glitziness of his room. Still, it was somewhat disconcerting to walk into the small space surrounded by the organized chaos Tan and Hobson had dumped into Grundman's lap.

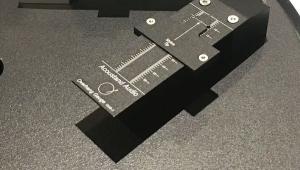

Boxes of RCA mastertapes- the ones that if thrust into your hands might start them shaking, sat neatly stacked and boxed in one corner. Behind Grundman is something rarely seen in a commercial mastering facility these days: a lacquer cutting lathe, in this case a large, fifties vintage cast aluminum bodied Sculley outfitted with a custom sprung, Haeco cutting head rebuilt by octogenarian Otto Hepp, designer and creator of the original Westrex cutters used throughout the industry during vinyl's heyday-including RCA which used them to cut the famous "shaded dogs". The unit is fitted with Grundman designed and built motor, amps and computer controller.

Many LP fans don't know this, but towards the end of the original vinyl era, even when the master tape was analogue, they were ultimately listening to digital. Mastering houses replaced the "preview head" which was used to "see" the upcoming signal and warn the cutting head controller of peaks, with a digital delay line. The purpose being to control the spacing of the grooves thus preventing large modulations from causing adjacent groove collision.

The analogue signal never made it to the cutter head- the DDL signal did. When I interviewed rock engineer Steve Albini a few years ago, he told me how he gutted the vinyl mastering system at Abbey Road studios, replacing the DDL with an analogue preview head.

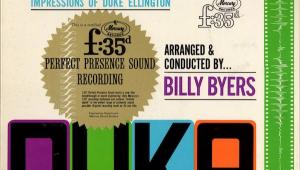

Obviously, Grundman's Studer is fitted with an analogue preview head and custom designed and built solid state electronics. When I showed up, Grundman was playing back the master tape of Back To Back- Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges Play the Blues(Verve MG VS6055) on his custom Studer A-80, and comparing it to an original pressing.

On what turntable? On the cutting lathe which was equipped with a Shure 3009 transcription length arm fitted with a V-15 TYpe IV. The

record confirmed the expectations of every analogue hater: it was rolled off at the frequency extremes, dynamically compressed, and the surface was noisy.

No one was surprised: the tape box cover included mastering notes describing the audible roll-off applied during the original lacquer cutting. The resulting boxy sound was typical of many Verve LPs of the era, but fortunately not of the recordings themselves. When the CDs were issued, no doubt, by comparison they were a revelation of clarity and frequency extension.

Grundman slapped a test lacquer on the lathe and after making a few adjustments, ran the tape again. With the SME tracking the just cut grooves, he "A/B" ed the master tape and the lacquer. Oh so close. Yes. Close- with a Shure MM cartridge. VPI's Harry Weisfeld is a fan and he's listened to many a master tape and of course, to many a turntable.

This is neither the forum, nor do we have the space to get into a cartridge debate. Take my word for this: Grundman's custom assembled vintage Tannoy monitors and his Crown amps ( early model with only a few solid state output devices) are of sufficient resolution to tell the veteran what is going down. That's obvious from the sound of this splendid series of reissues and Grundman's other work in and out of the audiophile community.

Different equipment would have resulted in different sounding LPs, just as different equipment in your chain would do the same. Had Doug Sax done the mastering the sound would have been different. Better? More like the originals? Not likely. Frankly, who cares?

Watching Grundman work was fascinating: even though he was handling priceless vintage tape, his demeanor was determined but almost casual and nonchalant. As usual, a real pro makes what's difficult look easy. Grundman's take on digitizing an analogue recording? : " When you change languages, something always gets lost in the translation". Amen.

Everything Grundman had to say about sound: analogue vs. digital, the sound of amplifiers, observational listening vs. measurements, was reassuring to these ears. Does he believe all amps that measure the same sound the same? No. Does he believe 16 bit 44.1K sampled digital is "perfect"? No. In fact Grundman says he can record onto both a 44.1K sampling recorder and one that records at 96K and "a man picked at random off the street" can easily hear the difference.

He related a story about digital clones whose waveforms, while looking identical on an oscilloscope, sounded so different that 9 of 9 trained listeners could easily pick the copies from the original- the source of this anecdote being Swiss engineer Roger Lagadec one of Sony's engineers responsible for creating the CD format. (Lagadec also admits that CD was never intended as a "high end" audio product).

While Grundman's goal here is to reproduce the sound of the master tape, judicious use of EQ is not ruled out. On some of the Classic issues a bit of bass boost is applied to counter a tendency toward bottom end thinness on a few of the old tapes.

Watching Grundman work with the famous Ella/Duke Porgy and Bess tapes was instructive ( the reissue was cancelled because the sound of the master tape was not as good as Classic hoped it would be). While some engineers might have been content to leave the "de-esser" circuit in-line during the cutting, Grundman chose to listen to the whole side, taking notes as to where the bad sibilants were. While cutting the lacquer, he activated the "de-esser" just before the sibilant and turned it off right after it. The "in/out" is inaudible, but this way the circuit is in only where needed.

Ed Tobin- the "Yoda" of Electro-Plating

Note: Tobin is now deceased. He was murdered.

Once the lacquer is cut, its rushed ( time is of the essence since lacquer grooves begin to loose their "memory" within 24 hours or less) over to Greg Lee Processing south of Los Angeles where Ed Tobin, a forty five year record manufacturing veteran handles the plating. Outside the front door is an ominous sign: " "Warning!! This facility contains one or more chemicals identified by the state of California as causing cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm."

With its stringent anti-pollution laws, operating an electro-plating facility in California is about as much fun as running an abortion clinic in Jerry Falwell's home town. But by taking the proper precautions inside the plant, and by spending big bucks on air scrubbing equipment, Greg Lee Processing manages to operate within the law. That meant changing from chrome plated lacquers to nickel, which Tobin says are satisfactory, but over the long run may not hold up quite as well as chrome.

How good is Tobin and co's work? The day I showed up metal parts were on hand for Mobile Fidelity, AudioQuest, Classic, Acoustic Sounds and Reference, among others. Tobin has a virtual monopoly in the audiophile record business, though he handles plating for many other record companies as well.

Compact discs are manufactured by lab coat wearing technicians working in dust free "clean rooms". Record pressing parts come from noisy, grimy looking spaces with no names: rooms filled with open vats of lethally charged caustic chemicals. Rooms manned by guys in gut protruding T shirts. Guys like Ed Tobin. But don't be deceived: Tobin is meticulous. He's a master artist with a knowing touch.

Before plating begins, Tobin brushes the lacquers thoroughly in a soapy bath of diluted Whisk laundry detergent to remove dirt and

dust. His hands move deliberately around the grooves, performing a ritual perfected over forty five years, beginning back in the days of the 78 RPM record.

The cleaned lacquer is dried in a dish rack-like device and then its ready to be plated with a silver solution applied by a spray gun. The finished silvered lacquer-a thing of beauty-is then ready for another bath, this time in an electro-plating solution of dissolved nickel which after several hours, forms an even coat over the entire silver surface.

Tobin "cracked" a lacquer for me with the nonchalance of shucking an oyster. The technique is the same. Crack the shell of an oyster, no big deal. Blow it here and the lacquer is ruined. The veteran turned out another perfect master, or "father". The "father", a positive copy of the lacquer, with ridges instead of grooves, is then replated to create a "mother". The grooved "mother" is then replated to create a positive "stamper". The "mother" can be used to create a number of stampers. Meanwhile, the plated lacquer is put in storage. That's the normal three step process. So-called "one step" process LPs are created by using the master to press the records. You get about 1000 LPs and then you have to start all over again.

- Log in or register to post comments