Analog Corner #119

“Sarah McBride’s assertion in today’s lead story that satellite radio offers ‘higher quality sound’ than FM radio is demonstrably incorrect. This is not a matter of opinion. While satellite radio is ‘digital,’ it is a highly compressed digital format. . . . I believe were you to speak with the chief engineer at Sirius or XM, and were they to be honest and candid, they would agree too that while satellite radio is a fantastic innovation and offers ‘noise free’ sound, FM offers demonstrably better sound than current satellite technology provides. I know if you spoke with the chief engineer at WGBH in Boston or [W]FMT in Chicago, they’d tell you the same thing.

“She commits another similar error on page P A-10 where she states that digital radio (HD radio) promises ‘CD-quality sound.’ This is simply not true. If you go to Ibiquity’s website (www.ibiquity.com/technology/index.htm), the inventor of this technology, you will find that they are very careful to state that the process broadcasts ‘compact disc–like quality.’ They are very, very careful to not claim ‘compact disc quality’ for the format, because it is not compact disc quality. In fact calling it ‘compact disc–like’ is a big, big stretch, and deliberate deception, sort of like calling frozen food ‘fresh food–like.’ It gets the ‘fresh’ association in, but we’re talking about two very different things. As with satellite, HD radio is ‘digital,’ but all ‘digital’ formats are not alike. This is not splitting hairs. Please. It is important to not allow these misstatements to stand uncorrected. The public deserves better. Your discerning readers deserve better.”

No correction was made, nor did I receive a response. I re-sent the letter a few days later, explaining in stronger language why this matters. Again, no response and no correction. I’m certain they now regard me as some sort of crank for wasting my time over such trivial distinctions. Meanwhile, inch by inch—or bit by bit—the race to the bottom of the sound barrel continues. Fresh and frozen are identical. Ripple equals Petrus. Wine is wine, digital is digital. Feel free to send a cordial e-mail to the WSJ’s corrections editor: wsjcontact@wsj.com.

Just before submitting this column, I sent a third e-mail to the corrections editor. Its gist was: “Had one of your reporters written a story confusing the FCC with the FTC and had someone submitted a correction, would your response be, ‘Big deal, only one letter different?’ Well, that’s basically what your nonresponse was to my request.” They replied, saying they’d look into it. I’ll let you know in the next column if they’ve done anything.

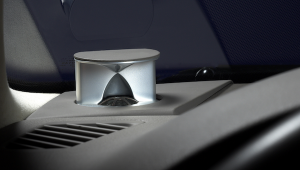

Whest PhonoStage.20 + MsU.20 phono preamplifier: Second listen

The Whest might not bowl you over when you first hear it. Unlike the Sutherland PhD ($3000), for instance, which immediately startles thanks to its exceptional liquidity, purity, and background quiet, the Whest’s greatest strength is its overall balance. It does everything well, but nothing exceptionally so. The Whest also exhibits no obvious weaknesses—neither immediately nor over time. The PhD, on the other hand, noticeably trades some dynamic slam, and especially transient speed and detail, to achieve its mesmerizing flow. That’s a tradeoff many happy PhD owners have been willing to make. You needn’t switch out phono preamps to notice what the PhD does exceedingly well, or to hear its shortcomings. The Whest, on the other hand, lowers the performance bar evenly compared to far more expensive phono preamps and, in so doing, simply gets out of the way. More music, fewer audiophile jollies.

When I wrote my original review, I’d cracked open the Whest’s main chassis, but not the case of its MsU.20 power supply. Now I have. Inside I found a high-quality toroidal transformer, but I also found that designer James Henriot had leveled the circuit board with a piece of folded-over cardboard. That’s tacky. In fact, for $2595 it’s downright amateurish. That shouldn’t stop you from considering the Whest, though.

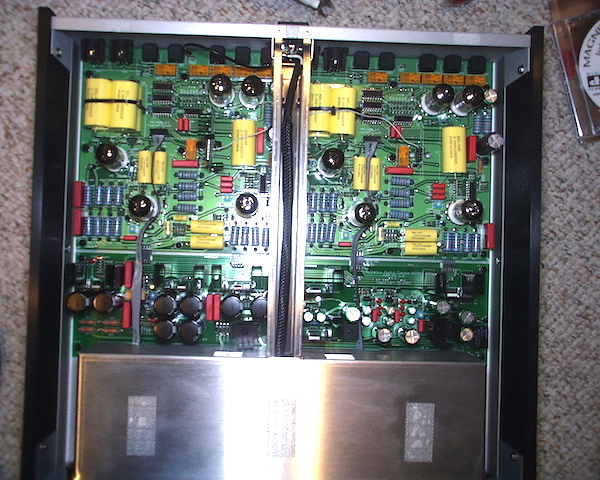

Musical Fidelity kW Phono Preamplifier

Like the phono preamp built into the kW preamp, the kW phono includes separate circuits and input jacks for moving-magnet and moving-coil cartridges, selectable via a button on the front panel. It also features both RIAA and IEC equalization, the latter a modification of the RIAA curve specifying an extension of the bottom-end frequency response from 20Hz down to 10Hz, with a –3dB rolloff at 20Hz to avoid amplifying turntable rumble and possibly accentuating the effects of record warps. Unfortunately, this can affect audible bass performance as well; a better solution would have been to put the subsonic rolloff point lower, or to simply add a switchable rumble filter at a far lower frequency. In any case, selectable IEC EQ is somewhat like having a rumble filter, and is worth experimenting with if you find your woofers pumping subsonically.

Each MM and MC input jack has its own very limited loading/capacitance options, accomplished via internal DIP switches. After my kW arrived, a revision added MC loading sockets, Musical Fidelity supplying a wide variety of resistor-equipped RCA plugs. Good thing! Very few audiophiles would want to spend $3500 on a phono preamp that offers a choice of only 10 or 100 ohms in MC mode. Owners of the original kW can get the update at no cost. I didn’t get a chance to try one of the updated units, so I set my kW to 100 ohms for the Lyra Titan cartridge, which usually likes to run more open.

The MM input offers a choice of 68k and 47k ohms (standard) in parallel with 47pF capacitance, with three more DIP switches allowing you to add 50pF, 100pF, 200pF, or any combination thereof. I ran the high-output London Reference cartridge (see review below) into the MM input at 247pF (London suggests 220pF). Gain is fixed at 40dB (MM) and 55dB (MC).

The kW’s specs are impeccable: very low noise and distortion, generous overload margins, and ultra-accurate RIAA EQ. (The full specs are available at www.musicalfidelity.com/mf/en/Products/kW/kWPhonoStage.) But I didn’t need a spec sheet to know that the kW was an extremely quiet, incredibly dynamic, and muscular phono preamp from which music erupted as from jet-black backdrops. The low noise floor made it easy to hear low-level details way into the rear reaches of the soundstage, and the most delicate and subtle microdynamic gestures made themselves known with unforced ease. I heard new musical details in virtually every recording I played, and that’s not hype.

Transients were fast and clean but not etched razor-sharp, and rhythm’n’pace was taut and snappy without glossing over musical valleys. Through the Wilson Audio MAXX2 speakers the bass performance was tight, well damped, supple, and under control.

The kW painted a transparent, wide-angled picture with a three-dimensional soundstage developing well behind the speakers in a deep, panoramic arc. Images were finely and precisely rendered without etch. The kW was neither warm nor cold, and neutral almost to a fault. Your choices of cables will be critical—if you don’t think wires make a difference, you’ll end up blaming the kW for the sound of your cables. Aside from the Boulder 2008, I have never heard so ruthlessly revealing a phono preamp, or one capable of delivering such robust dynamic—and, most important, musically involving—performance. Its ability to grip the loudspeakers and make them dance to the tune had me spending many evenings listening well past 2am, and finishing the sessions still feeling relaxed and refreshed. Of course, listening through such revealing, full-range, ultradynamic speakers as the Wilson MAXX2s didn’t hurt, but it sure helped me hear differences among the other components exiting and entering my system.

Although I felt I heard everything with the kW, even when optimally set up it will leave some people cold—especially tube lovers, some of whom will hear a hole in its musical heart and think its performance “skeletal.” If you like a sound that’s more warm, rich, and romantic than reality—and judging by how they vote with their pocketbooks, many audiophiles do—the kW will not be for you.

Aesthetix Rhea Phono Stage

But the Rhea’s sound is far more cozy, rich, and silky. While, like CD sound, the kW may be more technically accurate, it will leave many listeners—especially some classical music lovers—a bit chilled. Its transient delivery could sometimes edge toward harshness, and its harmonic development seemed to stop at the water’s edge compared to a tubed design.

I’ve just been sent two new, superbly recorded direct-to-disc LPs from Analogue Productions Originals. I’ve played one, bluesman Leroy Jodie Pierson’s D2D (no catalog number), through the Musical Fidelity kW, the Aesthetix Rhea (run at 47k ohms to make the comparison fair), and the revised Ayre P-5x (see review below) phono sections. While both the tubed Rhea and the FET-based Ayre put the closely miked bluesman in a barely discernible space (Blue Heaven Studios), the kW seemed less concerned with the space and more interested in the main event. Although one’s tubed and one’s solid-state, both the Rhea and the P-5x had creamier midbands than the kW. But neither could match the kW’s bottom-octave and dynamic presentation—it wasn’t even close.

If you have genuinely full-range speakers, do yourself a favor and listen to the kW. If you want musical infill to flesh out the impressive rhythmic and dynamic drama the kW delivers, it will have to come from the cartridge. The kW is more suited to a Koetsu cartridge than a van den Hul Colibri, for instance. The Lyra Titan and the London made devastatingly good partners. With 55dB gain in MC mode, I’d be cautious about using the kW with a cartridge that outputs much less than 2.5mV, though with its ultra-low noise and wide dynamics, you might be fine even then. If you want more of a Merlot finish than the kW seems capable of providing alone, you may find sonic nirvana running the MF X-10V3 tube buffer ($399, see “Sam’s Space,” December 2004) between the kW and your preamp, though I’d skip it if you listen mostly to rock.

All in all, Musical Fidelity’s first top-shelf phono preamp is an exceptionally attractive choice, regardless of price—but, like a high-performance sports car, it needs to be handled with care. This first work of phono-preamp art from Musical Fidelity is easily a Class A pick for “Recommended Components.” Add points for an exhaustive set of specifications.

The superbly designed and built Aesthetix Rhea—with its three independent inputs, remote-controlled loading and gain, auto demagnetization, and quiet, silky smooth, ultrarich sound—represents one of the best values in phono preamps now available. It, too, is a pick for Class A, though its personality is very different from the kW’s.

Ayre P-5xe Phono Preamplifier

I ran the P-5xe in both single-ended and balanced modes into the Aesthetix Calypso preamp, and it’s everything I said it was in the original review: extremely quiet (no noise specs are provided), gets out of the way, and lets the music through with a rich but detailed finish. The ride is softer than the Musical Fidelity kW’s, and it doesn’t deliver the same thunderous dynamic performance of the kW or the Manley Steelhead, both of which cost more. Its (adjustable) gain is greater overall than the kW’s: 64dB unbalanced, 70dB balanced). But if you use two tonearms, or multiple cartridges with different outputs and loading needs, the Ayre’s single output means you’ll be opening its chassis and switching DIP switches each time you change. Like the P-5x, the P-5xe is a swell product; like the Whest PhonoStage.20, it’s a bargain more for its overall pleasing balance than because it does any one thing extremely well.

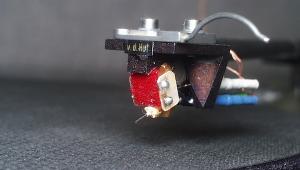

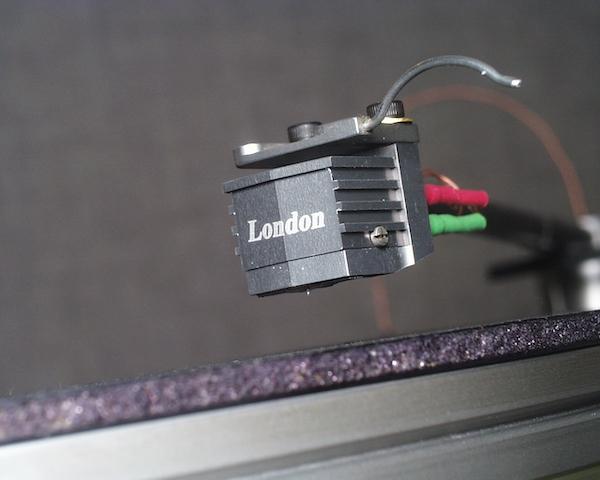

London Reference Phono Cartridge

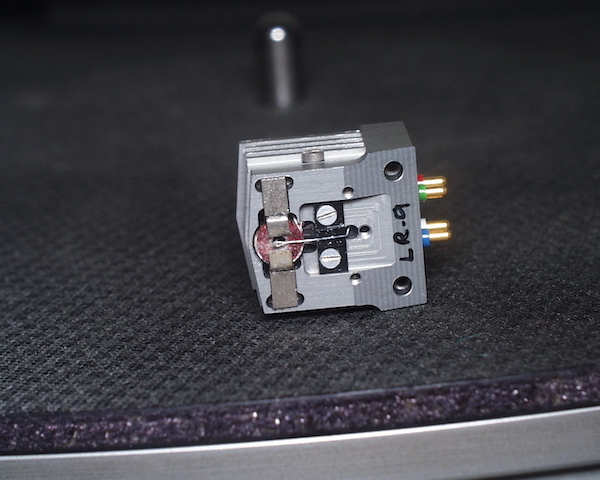

The London Reference ($4495) has no cantilever in the conventional sense. The stylus—in this case an ultra-low-mass fine-line design—fits into the tip of an L-shaped tempered steel blade that protrudes down through a cartridge body newly designed by Avid’s Conrad Mas. The other end of the L is clamped tightly within the body. A tiny tie-back cord affixed to the vertical “cantilever” just above the stylus is literally tied back and attached to the same set of clamping plates holding the other end of the L-shaped blade, thus creating a spring. The stylus end of the L passes through a coil-and-pole-piece assembly that tracks the lateral motion, while another coil and magnet at 90° to the lateral one registers the L piece’s vertical movement.

This design evolved from the original mono cartridge design, which is why the second coil assembly sits atop and at 90° to the original lateral (mono) coil, instead of in the 45°/45° configuration found in most, if not all, other stereo cartridges. Had I another few thousand words’ worth of space, I’d go into greater detail about this.

The result is a direct, low-mass connection between the stylus/groove interface and the current-generating system, which uses the sum/difference principle with a common ground. The result is also a system in which the horizontal and vertical compliances are very different—medium and low, respectively. And while a small amount of damping material is inserted between the lateral coil and the clamped end of the steel blade, there is not the usual cantilever damping, so a damped tonearm is recommended. The Reference’s output is huge: 5mV.

I installed the London Reference in the Immedia RPM tonearm. When I measured the vertical and horizontal resonant frequencies, they were quite different, but both were within the acceptable range—a good start. Tracking and antiskating force settings made enormous differences in getting this cartridge to sound right and track correctly. Anywhere between 1.5 and 2gm is recommended. Your results may well differ, so I won’t list mine. The suggested vertical tracking angle (VTA) is dead parallel with the record surface.

I had some serious grounding issues with the London Reference. While the cartridge was silent through both the Musical Fidelity kW and the Graham Slee Gold Mk.V phono preamps, I couldn’t eliminate a nasty hum through the Whest PhonoStage.20 or the Aesthetix Rhea. Nothing worked, including removing one of the cartridge’s ground clips, as recommended by its manufacturer, the UK’s Presence Audio.

You have never heard a snare drum or cymbal retrieved from a vinyl groove until you’ve heard what the London does. When tracking correctly, its transient delivery was nothing short of astonishing—by a laughable margin, the most realistic I’ve ever heard. The entire drum kit, in fact, from the kick drum up, left my mouth agape. The same with voices, which were delivered with a coherence—a wholeness—that was scary with the lights out. Rhythmically, dynamically, and, to a lesser degree, spatially, the London Reference is in a league of its own. It speaks with a single voice of authority as has no other cartridge in my experience.

I just got Pure Pleasure’s reissue of Last Night’s Dream (PP 7-63212), a Johnny Shines LP I’ve wowed show crowds with for years. My American Blue Horizon edition is good, but this Pallas pressing, cut by Ray Staff from the original analog tape, is much, much better. Recorded in Chicago at famous Ter-Mar Studios, Last Night’s Dream is made for the London Reference—as is Classic Records’ reissue of Willie Nelson’s Stardust. But not everything fared as well; in terms of both music and noise, it was difficult to predict what I was going to hear when I dropped the stylus in a groove. Some records that are silent when tracked by the Lyra Titan were full of pops, ticks, and other garbage through the London.

Some think the London tears through vinyl, but after playing some discs repeatedly, I didn’t find that to be the case. Setup, however, is critical—the utter lack of “wiggle room” is made more of a challenge because you can barely see the stylus tucked underneath the body, and there’s no cantilever with which to reference the zenith angle. And the London horribly mistracked some records and had difficulty with sibilants on others.

Would I make the London Reference my primary cartridge? No—its performance is too unpredictable. Would I recommend it for use as an auxiliary cartridge on a second tonearm? If you can drop $4495 and not worry and you play lots of jazz and rock, don’t hesitate—you’ll get your money’s worth with every play, and you’ll play it more often than not. There’s a mono configuration available, and as a mono cartridge—its original purpose in life—it must be stunning.

Sidebar 2: In Heavy Rotation

1) Grey De Lisle, The Graceful Ghost, Sugar Hill 180gm LP

2) Ben Harper and the Blind Boys of Alabama, There Will Be a Light,

Virgin 180gm LP

3) Miles Davis, Seven Steps: The Complete Columbia Recordings of Miles Davis 1963–1964, Mosaic 180gm LPs (10)

4) Wilco, A Ghost Is Born, Nonesuch/Rhino 180gm LPs (2)

5) Johnny Shines, Last Night’s Dream, Pure Pleasure 180gm LP

6) Arcade Fire, Funeral, Merge LP

7) Leroy Jodie Pierson, D2D, Analogue Productions Originals 180gm direct-to-disc LP

8) Stan Getz, Spring Is Here, Groove Note 45rpm 180gm LPs (2)

9) Spoon, Kill the Moonlight, Merge LP

10) Rilo Kiley, More Adventurous, Barsuk LP