I've read that some clean vinyl before every play. I get the concept but I struggle to get everything cleaned ONCE in 30-some years. It's work (sitting on the bathroom floor with a Nitty Gritty, fluids and various sleeves). I may get ten done in an hour before I'm terminally bored. The things we do for love.

Analog Corner #72

Chickens & CDs

Finally, the "perfect sound forever" chickens have come home to roost. "CDs Forever—No Scratch That," a splashy story in the February 2 Wall Street Journal, reports that there may be up to "300 million damaged compact discs out there." According to the article, written by a WSJ staffer, "An estimated $1 billion to $4 billion of unusable CDs [are] piling up in American living rooms."

Turns out that digital slobs face the same music as the analog variety—only in time-release fashion. If you don't handle your LPs with care, the damage is immediate. With CDs, it may take some time, but eventually they either skip or won't play at all.

Is this news to you? Of course not, but it is to millions of suckers who believed the hype they inhaled during the mid-'80s—including, according to the WSJ story, articles in both Time and the Washington Post, which declared CDs "virtually indestructible." Some myths die harder than others: the WSJ story repeats the one about CDs sounding better than LPs.

Meanwhile, the article reports, a multi-million-dollar industry has been built on resurrecting damaged discs that don't play at all or stick in one place like a—a—a broken record.

The Disc Doctor's Miracle Record Cleaner

It's not quite a multi-million-dollar biz, but between the vacuum-cleaning machines from VPI, Nitty Gritty, and Loricraft, and the fluids we spill to keep them operating, vinyl fanatics drop relatively big bucks on the pursuit of clean records and, we hope, pristine, silent surfaces.

My record-cleaning fluid of choice is The Disc Doctor's (www.discdoc.com) Miracle Record Cleaner. I also use non-alcoholic Torumat TM 7-XH, mostly on noisy or scratched LPs, which seem to benefit from its slight lubricating action. (My original Disc Doctor review ran in March 1997, Vol.20 No.3.)

Recently, some readers complained about the non-availability of Disc Doctor's record-cleaning products, so those products were removed from last April's "Recommended Components." The Disc Doctor, aka H. Duane Goldman, is a genuine chemist; he called to explain what had happened, and to assure me and you that his products are currently available. The supply problem had been caused by a changeover to a new applicator pad material and supplier, necessitated by the old supplier running out of the material and not being able to obtain more. Because the initial batches of the new pad material would not hold the backing adhesive properly, the fastidious Duane refused to ship any pads until a remedy could be found. The problem has now been solved, and pads are now available in sizes to fit records of every diameter.

Currently, a pint of Miracle Record Cleaner (good for 300–350 average-condition LPs) and a pair of brushes cost $62.40, including postage and handling. Buying a quart instead of a pint costs an additional $14.50. That much should keep you in business indefinitely—unless you're a ritual cleaner who never stops to actually play records. (You know who you are.) I asked Goldman to send me some fluid and two new pads.

As I wrote in my original review, Miracle Record Cleaner contains no isopropyl alcohol, which, according to the Disc Doc, extracts the fillers and extenders used in most vinyl formulations to increase elasticity. A stylus coursing through brittle vinyl can cause tiny chunks to break free, which is one of the causes of pops and ticks. However, Goldman's research convinced him that alcohol-free solutions were incapable of removing the mold-release compounds used to keep records from sticking in the press; his final formulation contains a very low concentration of the water-soluble alcohol 1-hydroxypropane (n-propanol).

The rest of the fluid is purified water and a number of "modern surfactants" (you don't want to be using old-fashioned surfactants, do you?), namely sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate, ammonium dimethylbenzenesulfonate, and triethanolammonium dodecylbenzenesulfonate. If you want to mix up your own record-cleaning formulation, you won't find these ingredients at your local Target (proper French pronunciation: "Tarjay"). Miracle Record Cleaner is a semi-concentrate that can be applied as-is to extremely dirty records, though Goldman recommends a 2:1 cleaner/distilled water solution for most LPs.

Disc Doctor's applicator pads, which look like sections of licorice I-beam, are made of a rubbery kind of material stiff enough to exert sufficient pressure on the record, but soft enough to give under excessive force—should it slip out of your hand, it won't destroy the record you're trying to clean. The pad itself is a broad expanse of black plush material that efficiently holds and spreads the fluid deep into the grooves. You'll feel that as you lift it off the record.

The Disc Doctor's suggested methodology (complete instructions included) is different from mine, but whatever you do, you can't simply apply his fluid and then wipe or vacuum it off. You must finish the job by applying steam-distilled water, which is why the brushes are sold in pairs, one for the fluid and one for the distilled water. The DD likes to air-dry his records in a dish rack. I prefer applying fluid with his applicator pad, removing most of it with an Allsop Orbitrac (but not to the point of total dryness), then dousing the record with distilled water using the second brush, and finishing by vacuuming the LP dry. The distilled-water bath and careful rinse are mandatory—if you let a residue of Miracle fluid dry on the LP, it will appear as a milky-white discoloration, and you'll hear it as lots of crunchy noise. If this happens, it's not a problem: it comes off with a distilled water bath.

When you're finished, your records will be clean, and will sound as good as they can—which can range from dead silent to better than you thought possible. My original copy of Fritz Reiner and the CSO's 1954 recording of Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra (RCA Living Stereo LSC-1806) looked perfect but suffered from a swishing sound at the beginning. I vacuum-cleaned it with other fluids many times but heard little improvement. After repeated applications of Miracle Record Cleaner, the record is now almost dead silent. I give the Disc Doctor's cleaning fluid and applicator pads my highest recommendation.

Excruciating AC Cord Comparison...Kept Short

Think about it: Electrical juice flows from the power-generating station to a substation, through miles and miles of cable to a pole in front of your house, and then to your circuit breaker and wall socket. That a 6' length of cord from wall socket to component should make such a big difference don't make no sense!

I'll leave it to others to tell you about filtering, RFI rejection, amount and type of conductor, winding geometry, and other reasons— don't ask me why AC cords should make any kind of significant sonic differences. But they do.

I chose to compare three 6' cords using the Hovland HP-100 preamp as the source: Hovland's own cord upgrade ($538, not currently in production), the Electra Glide Fatboy ($2000), and Wireworld's new Silver Electra Series III+ ($550). I then compared the Fatboy, Silver Electra, and PS Audio's Lab Cable ($600, reviewed by Robert Deutsch in December 2000) with the Chord CPM 3300 integrated amplifier (reviewed elsewhere in this issue).

LPs used in the comparison included: DCC Compact Classic's reissues of Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark and Nat King Cole's Love is the Thing, Mosaic's superb boxed set of Bill Evans' The Final Village Vanguard Sessions, June 1980, Analogue Productions' indispensable reissue of Janis Ian's Breaking Silence, an original black-label Vanguard Stereolab pressing of Ian and Sylvia's Northern Journey, various takes from the recent Groove Note direct-to-disc sessions with the Bill Cunliffe Trio (reported on in the May "Analog Corner"), and an original EmArcy and a Speakers Corner reissue of The Clifford Brown All Stars.

With the Hovland HP-100, Hovland's own cable was very detailed, but way too bright and etchy for my tastes—which surprised me, because those guys are obviously such good listeners. Electra Glide's Fatboy combined the Hovland's detail with stunning background silence, lush mids, rich midbass, and well-controlled deep bass, with an overall vivid three-dimensionality and focus. Not far behind and far less expensive was Wireworld's Silver Electra Series III+. It sounded ever so slightly "filtered" on top, but produced the most tactile images. It also made me realize that, in my report on the Naim Stageline phono section in the June issue's "Analog Corner," I was hearing the effects of the decisively coherent Wireworld cord as well as the sound of the phono stage itself. My mistake in not divulging the cord used in that review: the Silver Electra III+.

The expensive and very stiff Fatboy proved best overall in showcasing the Chord's astonishing speed and delivery of detail and transients, but both the Wireworld and PS Audio cables created lusher sounds, with greater midband delicacy and rounder images. Playing Classic's ultradynamic 45rpm reissue of Gershwin's Cuban Overture (RCA Living Stereo/Classic LSC-2586), I was astonished by how different the power cords made the record and the Chord sound. Electra Glide's Fatboy revealed the mechanical nature of record playing and spotlit the tape hiss while revealing amazing detail. The Wireworld and PS Audio sounded quite similar, but tamped down hiss and noise while creating a blacker background behind plush images. While the picture was somewhat softer overall, the transients of Earl Wild's piano still sounded impressively fast and natural, and overall three-dimensionality and image depth were superb. The differences these cords made to the overall sound of my system were not subtle.

Bottom line: With a rich-sounding tube amp, I'll bet the Fatboy would sing. If you're addicted to speed and detail and can drop two grand, you'll appreciate its performance, but for $550 and $600, respectively, Wireworld's Silver Electra III+ and PS Audio's Lab Cable provided a richly relaxing, nonmechanical musical presentation that some will prefer, depending on the rest of their system and their musical tastes.

Tri-Planar Mk.VI Ultimate tonearm

Back in late 1997, when I reviewed the Tri-Planar Mk.V Ultimate tonearm, designer Herb Papier asked if I knew anyone interested in taking over the company. Herb is getting on in years (he's an octogenarian), and while his mind was and still is sharp, his dexterity was slipping. I couldn't help him, but Dung Tri Mei, a young, enthusiastic analog fan (see "Analog Corner," April 2001), hooked up with Herb and bought the company.

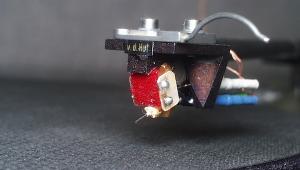

The Tri-Planar Mk.VI Ultimate ($3250 with 1m cable/RCA plug termination or 10" wire to RCA-jack junction box) builds on earlier versions with a larger-diameter headshell tube, a larger damping trough, and redesigned bearings featuring handmade hardened and polished needle cones. The clamping yoke that couples the headshell and bearing tubes has been redesigned, and a new lead damping insert is said to enhance imaging and extend soundstage depth. The main armtube also features improved damping via nine layers of internal material and annealing (ie, heat-hardening) of the armtube itself.

While I was curious to hear what sonic effects, if any, these subtle design changes might have on the arm's already superb performance, I was equally interested to see if Mei would continue building the Tri-Planar with Papier's care and attention to detail. Most of the arm's many parts are still being made by Papier's machinist in Maryland and sent to Minneapolis, where Mei resides.

Right out of the box, it was obvious that the Tri-Planar's build quality is still topnotch. In fact, the parts finish appeared superior to the sample I reviewed in 1997. Drilling an armboard was easy—the Tri-Planar is affixed with three screws, and there is no large-diameter central shaft. If you have an electric drill and some rudimentary mechanical skills, you can mount the Tri-Planar yourself with just a bit of care.

The instructions, however, need thorough rewriting, and the www.triplanar.com website contains incorrect price and product information. Dung Mei assured me that these errors will be corrected, but "I'm not superman," he kept telling me over the phone.

"I'm not asking you to leap tall buildings in a single bound, dude—just get the price right on your website!"

The Tri-Planar's cartridge-alignment hardware has been upgraded, and my sample came with an optional WallyTracktor laser-cut alignment gauge made specifically for the Tri-Planar, which is not surprising—Wally Malewicz, too, lives in Minneapolis. I'd wished for that in my 1997 writeup, and sure enough, it made cartridge alignment easy.

I still have a beef with the Tri-Planar's headshell design: the screw slots are way too wide. When you loosen the screws to adjust overhang and zenith, the cartridge can slide laterally, which is not good. The narrower slots on most other headshells prevent such unwanted movement.

The Tri-Planar was one of the first—if not the first—captured-bearing tonearm to offer easily adjustable VTA and azimuth adjustment. It's a two-piece design: a short section attached to the bearing assembly, and a longer one sitting above that holds the headshell. The two are connected via a substantial, machined aluminum yoke assembly fitted with dual locking screws.

The armtube system means that there is, in effect, a mechanical connector separating the arm from the bearing, but the yoke design is so massive and mechanically secure that I have no reservations about it whatsoever. In fact, the dual tube system has an advantage: the lower tube attached to the bearing assembly means that the bearing height will remain close to the plane of play, thus minimizing warp wow caused by forward/back deflection as the arm describes a vertical arc when tracking a warp. The only other tonearm I know of that maintains the bearing at the plane of play regardless of VTA setting is the Immedia RPM-2.

Azimuth is easily adjustable via a worm-gear drive that rotates the longer armtube around its vertical axis. However, due to the headshell's offset angle, the actual rotation pitches the stylus forward and back as well as from side to side. Only a rotation at the headshell can provide ideal azimuth motion, but it involves a more serious compromise: reduced arm rigidity.

VTA adjustment is via a substantial tower assembly topped by a dial attached to an internally mounted, locking worm-gear drive. The tower mechanism is one of the design's weak points—it also supports the entire arm mechanism, which hangs off of one side. When you unlock the tower to change VTA, the weight of the arm assembly causes the arm assembly to list to the right. Lock the tower and the arm rights itself, but this design is not the last word in stability in a system in which infinitesimal changes in geometry can have profound sonic effects.

The silicone damping trough, fitted forward of the bearing housing, features an adjustable screw that allows you to easily control the amount of damping actually applied to the system. Damping applied at the pivot point, as found on the Graham and VPI arms, is not nearly as effective.

The Tri-Planar is claimed to feature a decoupled counterweight, which would have the effect of creating a pair of much smaller resonant peaks on either side of the single peak you'd find with a hard-coupled counterweight. But there's no way the relatively hard elastomer rings inserted in the arm's various counterweights could possibly act to decouple them from the tonearm/cartridge system's resonant frequency, which should be around 12Hz.

A resonant frequency of 12Hz is considered ideal because it puts the resonance above warp/wow (most warps create oscillations below 10Hz), but below the lowest musical frequency (around 20Hz). The last thing you want to do is excite and accentuate the resonant frequency, whether with music or with warps. The resonant frequency of a truly decoupled counterweight must be equal to or below the system's resonant frequency, hopefully around 12Hz. A stiffly suspended counterweight such as the Tri-Planar's will have a much higher resonant frequency—probably in the audio bandwidth, which is not a good thing at all. If I bought the Mk.VI Ultimate, I'd try removing the inserts and replacing them with hard metal sleeves.

Tri-Planar Mk.VI Ultimate: Fundamental Sound

I auditioned the medium-mass (11gm effective mass) Tri-Planar Mk.VI Ultimate with the low-compliance Clearaudio Insider and the medium-compliance Lyra Helikon and Transfiguration Temper Supreme cartridges. With all three, the resonant frequency fell within the desired range.

The sound of the Tri-Planar had not changed appreciably since I last auditioned it: It offered unerring, rock-solid image and soundstage stability. The bass was extended and lithe, and high-frequency transients were cleanly presented. The picture was airy and big, but not quite as three-dimensional as with the Graham and Immedia arms. Image solidity was not quite as good either of those, but the sonic differences between the arms was minor compared to the differences between the cartridges, which is hardly surprising.

When I first reviewed the Tri-Planar, I found it somewhat bright-sounding compared to the Graham 1.5t, and somewhat bass-shy. But in 1998, after Herb Papier had changed to Discovery arm wire and added a damping trough, I found the overall balance far more neutral and the bass response deep and extremely well-controlled. That was the case this time as well, but I think the Tri-Planar was either slightly brighter or more extended on top than either the Graham 2.0 (with Hovland MG2 cable), or Immedia (with XLO Signature 3.1) tonearms. Whether you find the Tri-Planar "brighter" or "more extended" will depend on whether your water glass looks half empty or half full. I wonder about the effect of those "decoupled" counterweights on the sound.

In any case, The Tri-Planar's ability to resolve low-level detail was superb, and its tonal balance and frequency extension were exemplary. In every way, it remains one of the world's premier arms; we should all be thankful that it's still available to analog lovers everywhere.

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Shuggie Otis, Inspiration Information, Luaka Bop LPs (2)

2) Led Zeppelin, III, Classic 180gm LP

3) Led Zeppelin, IV, Classic 180gm LP

4) David Crosby, If I Could Only Remember My Name, Classic 180gm LP

5) The Blind Boys of Alabama, Spirit of the Century, Real World CD

6) Tim Buckley, Morning Glory Anthology, Rhino CDs (2)

7) Ted Sirota, Ted Sirota's Rebel Souls vs. the Forces of Evil, Naim CD

8) The Higher Burning Fire, In Plain Song, Second Nature CD

9) Graham Parker, Ultimate Collection, Hip-O CD

10) Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Live in New York City, Columbia LPs (3)

- Log in or register to post comments

If you have a spot to place your record cleaner it may become much less cumbersome to do. You could just clean the record right before you play it so you don't get bogged down with cleaning every record right when you get them home. This would be better also since it will be less likely to have any dust or sleeve remnants on it.

Possibly but that would result in even more time cleaning and also interrupt my listening sessions with tedium, probably leading to fewer platters spun. We all must decide where to draw the line with tweaking and fussing vs. listening, and listening to canned music (thanks to Dan Hicks) is the ultimate point of all this, isn't it? I know many people think I'm nuts to clean records at all.

Yes, I am one, a true CD fanatic! Only about 4 out of many hundreds of CDs have died, one lost in a fall from a high shelf and a couple of Nimbus CDs that were apparently not pressed correctly. My brother did have an RCA car player in his 1962 Galaxie 500. It played standard 45 RPMs upside down and was quite interesting to watch (for a 7-year-old at least). It was not a stereo, but he had a "vibrato" add-on unit to give that Big Sound to records like "Here Comes the Night" by Them.

Hi, disc doctor miracle record cleaner is great but it doesn't really come with instructions and Acoustic Sounds, which bought it, doesn't know anything about the product.

Do you happen to know whether you're supposed to leave the liquid on the record for a certain amount of time. Or do you just brush it on and wipe it off right away?