Analog Corner #90

Back in the mid-1980s, how many guys do you figure were hauling milk crates full of used LPs around America, from record fair to record fair? Hundreds? Thousands? How many are still doing it now?

That's how and when Acoustic Sounds' Chad Kassem got started—in, of all places, Salina, Kansas. In the early '80s, Kassem had gotten himself in more than a little trouble in New Orleans, and was given his marching orders by local district attorney Harry Connick, Sr., father of the famous duck-faced Harry Jr., who for some reason women are wild about (okay, I'm jealous).

"Leave New Orleans and don't come back until you make something of yourself," Connick told Kassem, and he has. But he ended up staying in Salina—a three-hour drive from Kansas City, Missouri—where he now runs Acoustic Sounds, Analogue Productions Originals, and Blue Heaven Studios, the last located in a deconsecrated church.

I paid my first visit to Salina this fall, for Kassem's fifth annual Blues at the Crossroads music festival. I traveled from KC with poor, put-upon Sam Tellig, who had to endure my driving, my sometimes paranoid political rants (this was before the second politically "convenient" plane crash), my "Mustapha the Terrorist" character—not to mention my vocal impressions of many audio journalists, whose bylines (if not their voices) are familiar to many of you. ST is probably still recovering from four days of my intense brand of mayhem. An old friend once described me as "a giant walking opinion." To which ol' Sam would probably say "Amen!" Or maybe "Never again!"

Chad Kassem is on a mission to preserve, in sight and audiophile sound, the remaining authentic blues greats. Based on what I observed at Blues at the Crossroads, he stands a good chance of being recognized as the Alan Lomax of our time. I predict that his work will eventually grace the Smithsonian. [The Blues Foundation, which has worked since 1980 to promote and preserve the blues worldwide, awarded Kassem its 2002 Keeping the Blues Alive Award last March.—Ed.]

The former church that is Blue Heaven has been outfitted with a state-of-the-art analog-and-digital recording studio and world-class video facilities. Along with his APO Records roster of elder statesmen of the blues, Kassem has been recording the annual fall concerts. If what I heard and saw those two nights is indicative of what's already in the vaults, there's a Fort Knox of musical treasures awaiting release in Salina.

This year's concerts were performed before more than 500 hardcore blues fans, some of whom came to Salina from overseas, and was recorded by renowned engineer David Baker to two-track analog and DSD, as well as to video. The evenings were filled with memorable moments, straying from classic blues to New Orleans funk with the original Ex-Cello label's house rhythm section—the guys who played on Slim Harpo's "Scratch My Back." But for me, the trip was worth taking just to experience the great Robert Lockwood, Jr., who, at 87, is probably the most vital living link to the original Delta blues scene. No musty relic, Lockwood played and sang with the vitality and musical complexity of a much younger man, though no youngster—even one capable of playing the identical notes—could possibly deliver the goods the way Lockwood did.

Lockwood's performance was mesmerizing and transporting. Salina's cool fall night seemed to become as warm and humid as the Mississippi Delta; the stage, the church walls, and the technology arrayed around the old man seemed to fade away, transporting the audience to another time and place. It was one of the most transcendent musical experiences of my life. When and if it's issued on LP, CD, SACD, and/or DVD, you'll get a glimpse of that evening's magic.

Despite his somewhat improbable success, Chad Kassem remains the wide-eyed, down-home Cajun boy I first encountered almost 15 years ago, during his milk-crate-hauling days. He clearly loves this music and these veteran musicians, few of whom have been treated with such care and respect. They feel the same about him.

Three Pro-Ject Turntables

More than 15,000 Pro-Ject turntables were sold in the UK in 2001. Most were the inexpensive, bottom-of-the-line Debut, which American importer Sumiko is not particularly keen on and doesn't import. The Debut is one step below the Pro-Ject 1.2, which Sumiko retails for $319, complete with Oyster cartridge. The 1.2 is similar to Music Hall's MMF-2, which comes with a Goldring Élan cartridge for $299.

Sumiko is probably not happy about Music Hall distributing turntables made at Pro-Ject's Litovel, Czech Republic factory, but that's neither my problem nor yours. While Music Hall's 'tables are not identical to those marketed under the Pro-Ject logo, they share many identical components. This month I review three Pro-Ject models: the RM-4 ($495), the Perspective ($995), and the RM-9 ($1495).

While the tonearm included with the Pro-Ject 1.2 and Music Hall MMF-2 is adequate in terms of adjustability and bearing friction, I don't recommend using it with an expensive high-resolution cartridge. All three of these 'tables (and the more expensive Music Halls) include Pro-Ject's premium 9" arm—a far more rugged and sophisticated design using superior-quality Swiss bearings and tempered-steel gimbals housed in a more rigid, sturdy, and massive pivot assembly. The RM-9's arm is further upgraded with even better bearings. One thing I don't like about these arms is the lack of a proper arm lock. The arms press-fit into a holder, but if you bump them with sufficient force, they pop out and go their own way. Use with extreme care, especially when installing a cartridge.

The tonearm used with the RM-4 and Perspective features a one-piece aluminum armtube that's stamped flat at the end to form the headshell. The back end of the tube is press-fitted into a cylinder suspended by the vertical and horizontal bearings. The RM-9 uses a variant of this arm fitted with a carbon-fiber tube, to which is attached a stamped headshell.

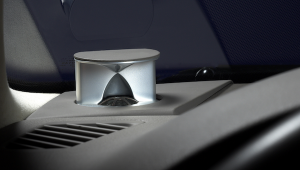

I auditioned all three 'tables on and off a relatively inexpensive but effective Townshend Seismic Sink—the original version, not the new and improved 3D ($400 and up, depending on platform size). The Sink uses an air bladder sandwiched between two constrained-layer-damped metal plates. The trick is to not overinflate the bladder, thus keeping the resonant frequency of the suspension low. A 12dB/octave rolloff will occur above resonance, so a resonant frequency of less than 10Hz is optimal. If the bladder is overinflated so that the resonant frequency of the system moves up to, say, 100Hz, rolling off above 100Hz won't provide any isolation at the critical bass frequencies. It's not enough to have "air" as a suspension, because air, like metal, can act as a spring. The key is the resonant frequency of the spring system.

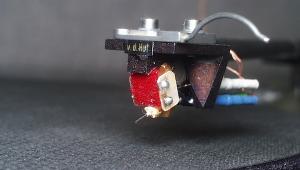

Sumiko's latest high-output (2.5mV) moving-coil (MC) cartridge, the Blue Point II ($249), is designed to track at 1.7gm. I used it as the reference cartridge for my auditioning of the Pro-Ject turntables (though I tried a Transfiguration Spirit as well), driving the built-in moving-magnet (MM) stage of Musical Fidelity's new Tri-Vista integrated amplifier (used only as a preamp). I played a wide variety of music I used to enjoy over and over on each turntable until I never wanted to listen to any of it again. How sad.

Using the Alesis MasterLink I reviewed last June, I made 24-bit/96kHz recordings of "Bluesville," from Analogue Productions' excellent 180gm reissue of Count Basie's 88 Basie Street (Pablo 2310-901); and "Let Me Touch You for Awhile," from a superb-sounding 180gm reissue of Alison Krauss and Union Station's New Favorite (Diverse DIV001LP). The Basie record, recorded by Allen Sides at Ocean Way in 1983, demonstrates large- and small-scale dynamic contrasts, bass control and extension, and the timbral accuracy of a wide variety of instruments. The Krauss, recorded to DSD and cut from the DSD master, highlights the female voice, bass tonality and dynamics, soundstaging, resolution of low-level detail, and transient speed. At the end of the auditions, I was able to play back each turntable's performance on those tracks almost in real time.

Just for the fun or it, I inserted the same tracks played on my reference front end: Simon Yorke turntable, Immedia RPM2 tonearm, Lyra Titan MC cartridge, and Manley Steelhead phono preamplifier. (Just so Bob Graham doesn't read this and jump out a window: I'm currently using the mono Helikon cartridge on his 2.2 tonearm.) Was my ca $27,000 reference rig that much better than these low-priced front ends? You'd better believe it. But all three Pro-Ject 'tables delivered "the essence of analog," and performed at comfortably competent levels.

Pro-Ject RM-4: $495 gets you a thick, lightweight plinth of sculpted MDF, a wall-wart–powered AC motor suspended by an elastomer band, an HDF platter driven by a flat belt and riding on a hard plastic subplatter, and a threaded-bearing spindle. A felt mat, threaded record clamp, and a set of gold-plated RCA interconnects are included, along with a dustcover. I was tempted to use a better interconnect, but decided to use what was supplied. The overall fit'n'finish of the 'tables coming from the Czech factory has improved in the last five years or so, and the entire package was very well presented and put together.

Buyers too anxious to spin LPs to read the instruction manual will no doubt miss where it says to please remove the two shipping screws securing the suspended motor, so the motor can hang by its rubber suspension instead of being locked down to the plinth. This design can do a decent job of isolating motor vibration, but it can't be great for speed stability—the motor movement caused by the vibration will continually vary the distance from pulley to platter, and thus the platter's speed of rotation. Granted, the speed changes will be on the microcosmic level, but considering the size of the wavelengths etched into the grooves, that's where the action is.

Setting up the arm was straightforward, though I found the cartridge-pin connectors way too loose on my sample; I had to carefully tighten them using miniature needle-nosed pliers and a toothpick insert (to keep the connectors from collapsing). Analog virgins unaware of the ramifications of loose connectors might end up with serious hum or no sound at all from one or both channels. Speaking of serious, the instructions describe setting azimuth as "VTA Adjustment." What's that about? Hasn't Pro-Ject been doing this long enough to know the difference? Can you imagine the confusion such mislabeling might cause, especially among analog neophytes?

You can adjust VTA by raising or lowering the mounting tube after loosening a pair of locking screws; azimuth is set by rotating the armtube within its rear mount after loosening a set screw that's somewhat tricky to access. Stylus pressure is adjusted by first rotating the decoupled counterweight until the arm balances, then setting the desired pressure by turning the weight inward toward the pivot, using the calibrated inner ring. Pro-Ject doesn't bother with decimal points; "15" means "1.5gm." And don't trust the built-in gauge—it's a rough estimate. The $15 or so you'll spend for Shure's fulcrum-style gauge will be well worth the more accurate results.

A soft elastomer insert makes it feel as if the counterweight really is decoupled (its resonant frequency is below the audioband) and not "spring-loaded," like Rega's self-defeating O-ring mount. Antiskating is set with a weight suspended by a nylon thread, which drapes over a thin looped support bracket. Pro-Ject specifies the distance between the loop and the horizontal pivot point, which you should double-check before engaging the antiskating, as its position affects the accuracy of the setting. Still, you have only three antiskating choices, and the instructions inconveniently refer to stylus pressure in millinewtons (mN) instead of in grams.

Using the RM-4 was straightforward: Clamp a record to the felt mat, flip the On/Off rocker switch, and you're ready to rock. My sample ran about 0.5% fast, or well within acceptable limits (1000Hz was approximately 1004Hz). The RM-4 is a decent place to start an analog journey, but you won't want to stay there too long once you get hooked on the format. It committed no gross errors, ran impressively quiet and smooth, and its arm could do justice to any reasonably priced cartridge you might consider using (and so will preserve your valuable vinyl).

But the RM-4 was limited in its ability to carve out instruments in three-dimensional space, its dynamic capabilities were somewhat stunted, and it did only a so-so job of resolving low-level details. Transients were somewhat softened, and bass, while impressively extended, was robbed of articulation and rhythmic drive. On the plus side, the RM-4 avoided the hard, metallic, hollow sound of some budget 'tables. Soft and warm is definitely preferable.

Switching between the RM-4's rendition of the Basie track and what the more expensive 'tables offered easily demonstrated the RM-4's limitations. There's a bass vamp that, when rendered properly, can feel like mountain-climbing. Through the RM-4, it simply spurted sideways. Basie's piano can sound harmonically rich, woody, and percussively complex with the finer turntables, or monochromatic and indistinct, as it did through the RM-4 and some other modestly priced 'tables.

I'm being tough on the RM-4 only because, while it made pleasant music and its sins were almost all of omission, there's so much more information in the grooves to be retrieved. If you can buy the Pro-Ject Perspective, at twice the price, you'll get more than twice your money's worth. However, if $495 is your limit, don't be discouraged: the RM-4 will deliver analog's expressiveness as no CD player at any price can, and, if set up correctly, the tonearm will preserve your vinyl until you're able to move up to something better.

I'm no fan of felt mats: they attract dust, and they can cling to a record, lifting off with it to easily slide off and lunch your stylus. I tried the $90 Ringmat XLR in place of the RM-4's felt mat/clamp combo, and it improved the sound by seeming to tighten up the bass and render the sound with somewhat greater clarity. But how many people spending $500 on a turntable are going to spend another $90 for a piece of paper with some cork rings on it, good as it is? Still, the Ringmat is a worthwhile addition. And try the supplied felt mat without the clamp—you might be surprised to find you prefer the sound to using the clamp.

Pro-Ject Perspective: The Perspective ($995) features the same tonearm as the RM-4, and a similar but not identical main bearing and subplatter. A Teflon thrust plate replaces the RM-4's sapphire one. Both of these main bearings are skinny affairs compared to the industrial-strength bearings you find in far costlier 'tables, but that's one of the significant upgrades you get when you spend more.

The Perspective's biggest improvement over the RM-4 is its ingenious silicone-damped, suspended subchassis. Both the main bearing and tonearm are affixed to a ¼"-thick aluminum plate that sits on three springs housed in cups attached to a ¾"-thick acrylic base. Damping is applied by a threaded rod fitted through the plate into a cup of silicone attached to the base. The further the screw protrudes into the cup, the greater the damping. Another small spring, attached to the base and connected at the other end to the main bearing housing under the plate, limits horizontal movement.

The heavy cast-alloy/vinyl sandwich platter (the vinyl is said to come from recycled LPs) is individually balanced and driven by a flat belt around its circumference. There are two wall-wart–driven AC motor modules: one each for 331/3 and 45rpm. Both feature precision-machined aluminum pulleys. Changing modules is relatively painless, though somewhat more difficult and time-consuming than simply moving the belt to an adjacent pulley: you have to reach under the acrylic base and unscrew a threaded retainer. Pop in the desired module, secure it with the retainer, affix the belt, and you're ready to play.

Setup was straightforward: First, level the base using the three threaded feet, then level the subchassis, if necessary, via the three spring mounts. There's a built-in spirit bubble on the subchassis, but for greater accuracy you're better off using a separate bubble level placed on the platter along the stylus path. How much damping you apply via the threaded rod will depend mostly on the springiness of your floor and the amount of stylus bounce you get from foot traffic, though it can have an effect on the overall sound as well.

Properly set-up, 'tables with suspended chassis can sound great. Too often, however, the result is soft, diffuse, and rhythmically weak musical reproduction. It's important for the subchassis to behave pistonically when deflected, and not rock back and forth. The Perspective's subchassis behaved well, helped in part, I'm sure, by the cup of damping silicone. You can knock yourself out and tweak the three spring towers to achieve perfection in this, but I didn't. Pro-Ject supplies the same interconnects and clamp as with the RM-4, plus a hinged dustcover.

The Perspective took a giant step past the RM-4 in every way. Music emerged from a far blacker background to achieve the "floating sensation" you get with the better turntables, suspended or not. Instruments inhabited separate spaces and attained a greater level of solidity and three-dimensionality. The bass was tighter and more articulate. The bass vamp on the Basie track exhibited genuine musical traction, the piano far greater harmonic complexity and percussive bite. Dynamics improved markedly, and while these observations were made during "live" listening, they were easily backed up in quick A/B comparisons via the Masterlink's 24/96 recordings. Rhythm and drive scored big as well, with much greater snap, drive, and excitement, although, like the RM-4, the Perspective ran slightly fast.

The Pro-Ject Perspective in many ways would almost satisfy the sonic needs of the most picky analog devotee. You give up significant performance at the frequency extremes, there's a bit of mush in the upper midband, and the overall sound is down a few pegs from the top guns, especially in terms of weight and solidity. But sit most tweakos—those who love music—down to listen without showing them what's playing, and I think they'll just enjoy the music and forget about the hardware.

Again, I preferred the sound of an unclamped record with the Ringmat to a clamped record with the felt mat, but you might not. The Pro-Ject Perspective is a great place to begin one's analog journey. How it compares with Music Hall's MMF-7, which features a split plinth, inboard/outboard motor, and acrylic platter, I can't say—but for the same price as the Perspective Music Hall supplies a high-output Goldring Eroica cartridge, which, with its Gyger Fineline stylus, is hardly an afterthought.

Pro-Ject RM-9: Costing $500 more than the Perspective, the $1495 Pro-Ject RM-9 seems to offer less. There's no suspension, and the MDF plinth is the diameter of the acrylic platter, with just enough of a "bumpout" to mount the arm on. The outboard motor sits on a platform that raises it to the proper height, and the platter is driven via a square belt around its circumference.

The RM-9's big news is its inverted thrust bearing with integral Teflon ball, which fits in a brass boss (sleeve) affixed to the bottom of the platter. This puts the turntable's center of gravity well below the bearing contact point, for greater speed stability. The more rigid carbon-fiber variant of the Pro-Ject arm is fitted with higher-quality bearings and so can better handle more sophisticated, low-compliance MC cartridges. A heavy nonclamping record weight is included, along with a set of the interconnects provided with the other 'tables reviewed here. A dustcover costs $100 extra.

The plinth sits on three elastomer-damped, height-adjustable feet, but depending on where you place the RM-9, you might need an additional isolation device, such as a Townshend Seismic Sink, to prevent skipping or feedback.

The RM-9 is for those who prefer a slightly faster, punchier, and rhythmically taut ride than the Perspective gives. While the outboard motor should theoretically offer lower background noise, that didn't translate into anything I was able to hear, whether playing a silent grooved record or normal program material. The improvement in speed stability was noticeable in better transients and greater musical drive and excitement.

The RM-9 ran slightly slow, no matter the distance between motor and plinth. (A useful template is supplied to help you set that distance, but when I varied it to see if the speed error could be corrected, it couldn't.)

Overall, I admired the RM-9's clarity and drive, and its ability to more precisely define images in space compared to the Perspective, but I'm not sure it's worth the extra $500, especially when you could put that money into a better cartridge (and never mind that you might also need an isolation device). Not everyone will agree with me on this, but few $500 cartridges sound "rich"; the Perspective, whether because of its suspension or something else, added a pleasant "richness" to the sound that the Pro-Ject RM-9 did not.

Next Time: Three more turntables—the Rega P3, the SOTA Comet, and the Nottingham Analogue Horizon—plus Graham Engineering's Rega-compatible Robin tonearm.

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Nora Jones, Come Away With Me, Classic Quiex SV-P 200gm LP

2) Søgur Ros, Fat Cat/MCA CD

3) Linda Thompson, Fashionably Late, DBK Works 180gm LP

4) Bill Evans Trio, Waltz for Debby, Analogue Productions 45rpm 180gm LPs (2)

5) Jefferson Airplane, Surrealistic Pillow, Sundazed 180gm mono LP

6) Eden Atwood, The Bossa Nova Session, Groove Note 180gm LP

7) The Rolling Stones, Aftermath—U.S., ABKCO SACD/CD

8) Johnny Griffin, Chicago Calling, Classic Quiex SV-P 200gm mono LP

9) Johnny Cash, Get Rhythm, Get Back 180gm mono LP

10) Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde, Sundazed 180gm mono LP