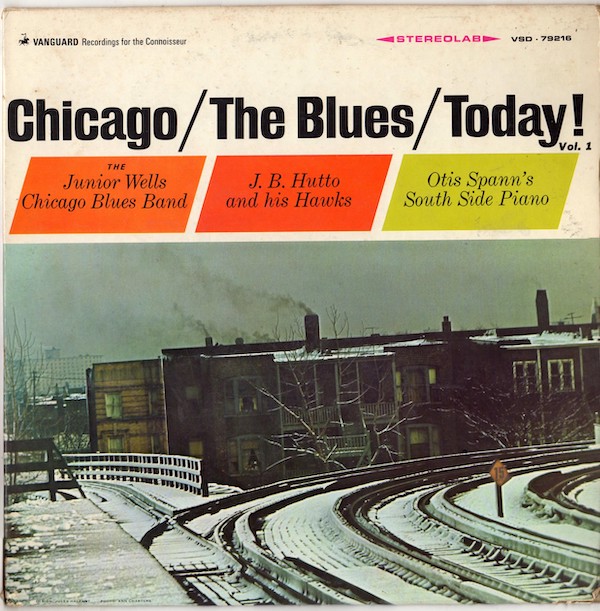

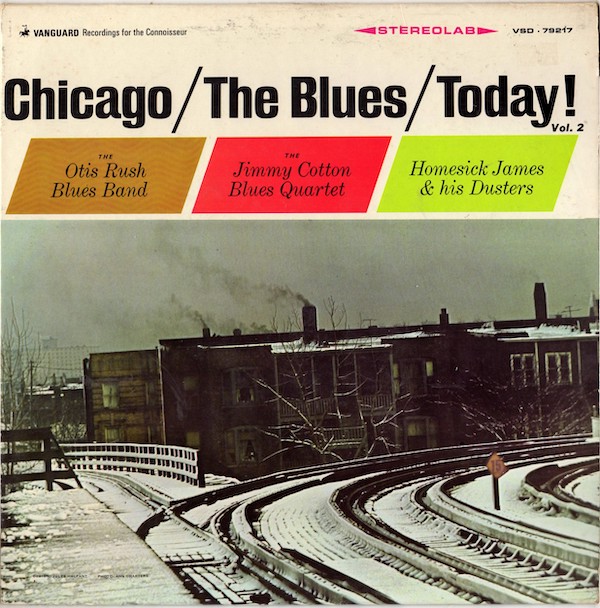

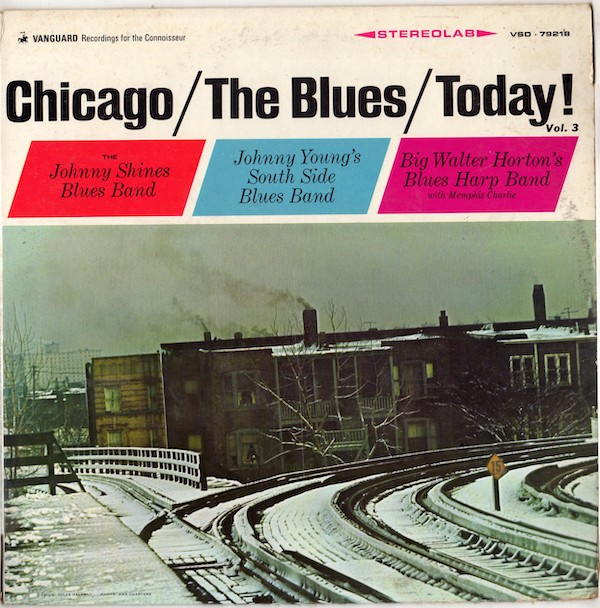

Chicago/ Blues/ Today! Vols 1,2 & 3 Vanguard Craft CR 00351 Record Store Day June 2021---The Records You Didn’t Know You Needed #7

Volume 1 of Chicago/The Blues/Today! begins with five tunes by Junior Wells (1934-1998 b. Memphis TN) harmonica and vocals, accompanied by Buddy Guy (1936- b. Lettsworth LA) on guitar with bass and drums. Wells’ style is the most modern of any of the musicians Charters recorded. His gritty vocals show the influence of soul and r&b and “Messin’ With The Kid” and “All Night Long” (aka “Rock Me Baby’) are played with a soul/proto funk rhythms. Buddy Guy plays wonderfully on all the tracks but his solo on “All Night Long” is especially stunning and inventive. “A Tribute To Sonny Boy Williamson” is a burning version of Sonny Boy’s “Help Me.” After the spoken dedication, the band grooves on the “Green Onions” chord pattern, while Wells plays a funky, rhythmic harmonica solo with lots of Sonny Boy licks. Wells and Guy together and individually had long and successful careers. Wells had some minor R&B hits, appeared in the Blues Brothers movie, and toured constantly until his death. Guy has won multiple Grammy awards, been inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame and his 1991 CD, Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues with guest artists, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, and Mark Knopfler was a crossover hit.

J.B. Hutto (1926-1983 b. Blackville S.C) was maybe the least sophisticated musician Charters recorded. His style is straight out of Elmore James, but cruder. with raw, wailing slide guitar and shouting vocals. No subtlety here, just rocking bar room blues. “Too Much Alcohol” starts with the “Dust My Broom” theme, the most overused, “but it’s just as good the millionth time”, ass shaking, fill the dance floor riff, in Blues. The groove is so strong and the vocal so intense that it’s a masterpiece. Rory Gallagher covered the tune but he and his band couldn’t rock this hard. “That’s The Truth” is an all out “shake your moneymaker” dance number. Hutto’s guitar solos are ridiculously simple but perfect. Hutto had a long career, made some classic albums for Delmark and Varick, and always beautifully avoided sophistication and subtlety. Otis Spann (1924 or 1930-1970 b. Jackson or Belzoni MS) was the pianist for the Muddy Waters Band and here he’s accompanied only by the band’s drummer. Spann was a powerful two-handed pianist, playing boogie or insistent “slow drag” rhythms with the left hand while his right, one of the most facile in blues, played cascades of melodic variations. He was also a limited but effective singer with a hoarse, soulful, “telling you my true story” voice. The two vocal numbers here, “Burning Fire” and “Sometimes I Wonder” are very “blue” and affecting performances with, for Blues, extremely adventurous right-hand runs.

Volume 2 begins with The Jimmy (James) Cotton (1935-2017 b. Tunica MS) Blues Quartet which was the contemporary Muddy Waters Band without Muddy. “Cotton Crop Blues” is a great stomping version, driven by Spann’s piano, of a tune Cotton had recorded in 1954 for Sam Phillips at Sun. This version is much better. Cotton’s vocal is more mature and intense and his harmonica solo is a wailing, nearly out of control gem. “Rocket 88”, one of the tunes always mentioned in those pointless “What Was the First rock ‘n roll Record?” articles, is more up tempo than the Jackie Brenston original with pounding drums, boogieing Spann piano, and lots of hard blowing, rocking harmonica. Cotton went on to have a long, successful career, playing the rock ballrooms in the sixties and eventually recording an album with Gregg Allman and a host of rock star guests, but these are probably his best recordings.

Otis Rush (1934-2018 b. Philadelphia MS) was one of the greatest talents in post-war Chicago Blues, but never achieved the “bigger than blues” crossover to the rock audience success that Muddy, Wolf, Guy, and Wells did. Refusal to compromise, erratic performances, a penchant for dark, emotionally distraught songs rather than party music, a difficult personality and a long mid-career retirement, all probably played a role, as well as a paucity of recordings, with even fewer of those showing him at his best. Charters’ recordings of Rush are a typically mixed bag. “I Can’t Quit You Baby” is one of the greatest recordings of Chicago Blues. Rush’s impassioned, shouting but sweet, with breaks into falsetto, vocal is so emotionally powerful that it’s easy to ignore the beautiful horn arrangement and the perfect and appropriately repetitive, stinging guitar solo. The tune was featured on the Led Zeppelin album and many have claimed that Jimmy Page exactly copied Rush’s arrangement. I won’t go that far, but it is very similar. “It’s My Own Fault” is another expression of masochistic self loathing that features an emotional vocal and lots of brilliant guitar. Rush being Rush, there are two instrumentals that are well played but lightweight throwaways compared to the vocal tracks. Homesick James (1910-2006 b. Somerville TN) claimed to be a cousin of Elmore James. This was probably not true, but he did play in Elmore’s band. It’s blatantly obvious that Homesick’s vocal and slide guitar style are a near copy of Elmore. If there could be any doubt, the first of his four tunes is “Dust My Broom” and one of the others is “Set A Date”, also an Elmore song. The other two tunes are Elmore pastiches. Homesick is an Elmore James imitator, but he’s a good one and “does” Elmore much better than Jeremy Spencer did on the early Fleetwood Mac albums. I doubt in Chicago Blues clubs in 1965, anybody, especially after a few drinks, cared that Homesick was basically a “Tribute to Elmore” act. The music was exciting and raucous and great barroom blues.

Volume 3 starts with Johnny Young (1918-1974 b. Vicksburg MS) who was unique in Chicago blues in that he played mandolin as well as guitar. His musical roots were in the country string bands popular in the 30s in Tennessee and Mississippi but when he moved North, he adapted to the more aggressive postwar sound. Here he is accompanied by bass and drums and the great harmonica player, Walter Horton who plays without an amp. The music has the more up tempo, lighter, rhythmic feel of late 30s Blues coupled with Young’s modern shouting vocal style. Horton’s effortlessly swinging virtuoso country style harmonica playing is the highlight of the session. When he solos and is backed by Young’s guitar or mandolin, their wonderful interplay makes it obvious that they had spent many hours playing together at “raising the rent” parties. “Stealin Back” is country dance/street corner music and the most rural track on the albums. After Young’s bluesy, swinging mandolin solo, the hat would have been filled.

Johnny Shines (1915-1992 b. Frayser TN) traveled and played with Robert Johnson for two years in about 1933 (There’s a photo that is purportedly of them together). Not surprisingly, his repertoire and guitar and vocal styles were heavily influenced by Johnson. At the time of the Charters recordings, Shines had not been working in music, but he must have been practicing or playing for fun because he is in great form. “Dynaflow Blues” is a version of Johnson’s “Terraplane” with Shines’ powerful vocal breaking into a pure falsetto while his slide guitar plays a boogie rhythm accompanied by backbeat drumming. This is probably as close as we will ever get to hearing Robert Johnson playing with a band in a juke joint. “Black Spider Blues” has another Johnson style vocal. Shines’ voice is deeper, bigger, and would have been more effective on street corners and in juke joints but lacks Johnson’s haunting mystique. Walter Horton’s harmonica accompaniment is a master class in how to accompany a blues vocalist. This music certainly was not “Chicago Blues Today!” in 1965, but was the music of southern juke joints in the mid 40s and early 50s. We are fortunate that Charters preserved it in such excellent recording quality. Walter Horton (1921-1981 b. Horn Lake MS) got only one featured track, “Rockin My Boogie” with Charlie Musselwhite (1944- b Kosciusko MS) on second harmonica. Horton, seemingly playing through an amp, displays his effortless swinging groove and subtle rhythmic sense while quoting “St. Louis blues” and playing the blues in E flat. He gives Musselwhite who wasn’t to record his first album for more than a year, a short solo and he shows that he was already a talented player. In June 2021 Craft Recording released all three Chicago/Blues/Today! LPs as a set in a Record Store Day edition limited to 3000 copies worldwide. I bought it at a record store for $70. The set can be currently found on the incessantly reviled “secondary market” for not much more. Unlike the original records, which were released individually with matching covers, the Craft set comes in a three pocket gatefold with the records inserted in individual flimsy cardboard jackets with scanned duplication of the original covers. The records are not in sleeves inside the jackets. I’m not demanding rice paper but plastic sleeves, I would contend, are a minimum for an audiophile reissue. No sleeves at all seems to me to show little respect for the product and the customer. The three pocket gatefold is not of the quality that the top rank audiophile labels are producing. The cardboard is thin, not glossy and I would say the over/under on the pockets splitting apart with even moderate, careful handling and luck is, maybe, two years. The cover scans are not well done, the color is off and the evocative elevated subway photos are blurred. Craft made an attempt to duplicate the original Vanguard record labels but failed miserably. The print is all wrong and the color is too. Inside, on the gatefold, are printed liner notes by critic Ed Ward and Sam Charters from the 1999 CD issue. A short update piece, in my opinion, should have been included. Charters and three of the musicians have died since 1999 and the place of the Blues in Chicago and our culture has changed dramatically in the last twenty-two years. Quoting from the hype sticker, “ALL-ANALOG (their caps and bold not mine) mastering from the original stereo tapes by Kevin Gray (again, their bold)…pressed on 180-gram vinyl (them again) at MPO.” Obviously, someone at Craft decided that “All-Analog” was their number one selling point and that Kevin Gray mastering and 180-gram vinyl was tied for second. Pressing at MPO was worth mentioning but not worth bragging about. Maybe that someone at Craft had listened to the records or looked at them before they wrote the copy on the sticker, because the pressings are indeed nothing to brag about (it's kind of unfair to ask Craft to inspect every pressing of these records, don't you think?_ed). Side 1 of Volume 1, when inspected upon opening the set, had two moderately sized, clearly visible, pressing dimples. They each caused a few thumps. The record was also moderately warped and the stylus would not track the run in groove. There was also a small mark running with the grooves that caused a few ticks. All three LPs played throughout with light surface noise especially audible between tracks and during quiet passages of the music. There were also occasional random ticks. It is possible that I have been spoiled by the ultra clean, ultra quiet pressings that the admired audiophile labels are producing, but I must say that these records fall very far short of that standard. I own original Vanguard stereo pressings of all three Chicago/Blues/Today! volumes and compared them to the Craft issues. They sounded quite a bit different. The original recordings, by uncredited engineers at RCA in Chicago are very well done, in a minimalistic, just the musicians playing in the room style. Kevin Gray’s excellent mastering presents a warmer, more tonally well balanced and somehow, more modern sounding version of the music. Immediately obvious is that the Craft LPs have much more bass than the Vanguard records. The result is a deeper, more dynamic rhythm groove which makes the music feel more aggressive and is a good thing for rocking, shouting Blues. Similarly. the tonal spectrum from midrange to treble is shifted slightly lower on the Craft records, taking a bit of the edge off the vocals which I thought was a slight negative. The recordings were made without overdubbing and the vocals were recorded at the same time as the instruments. I wonder if there was some leakage from the drums into the vocal mike because the mix on the Vanguard LPs is not ideal. There is frequently a wide gap between the vocals, over on the right with the drums and the instruments in the center. Gray has managed in many cases to close, if not entirely eliminate the gap. I strongly suspect that the original tapes have suffered some age or wear deterioration. The Vanguard LPs clearly have more presence and air. It’s especially noticeable that the vocals sound more human and less like a recording. The Vanguard LPs with their tipped up, slightly harsher, tonal balance and the additional presence have a wilder, sixties vintage sound which I think suits the music better. Clean copies of all three Vanguard LPs can be purchased for about the same total amount as the Craft set. The packaging of the Craft set is subpar as are the pressings. The covers of the Vanguard LPs look better even after 55 plus years and, if clean, the records play better. They are also the original issues of some of the most historically important Blues records ever to be released and as such, historical artifacts. If you have any interest in the Blues, American Roots music or are just curious about who Clapton, Mayall, Page, Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, the Allmans, and too many others to name, learned from, I advise you to buy original issues of the Vanguard LPs. (The Pure Pleasure box set reissue was reviewed here on AnalogPlanet.