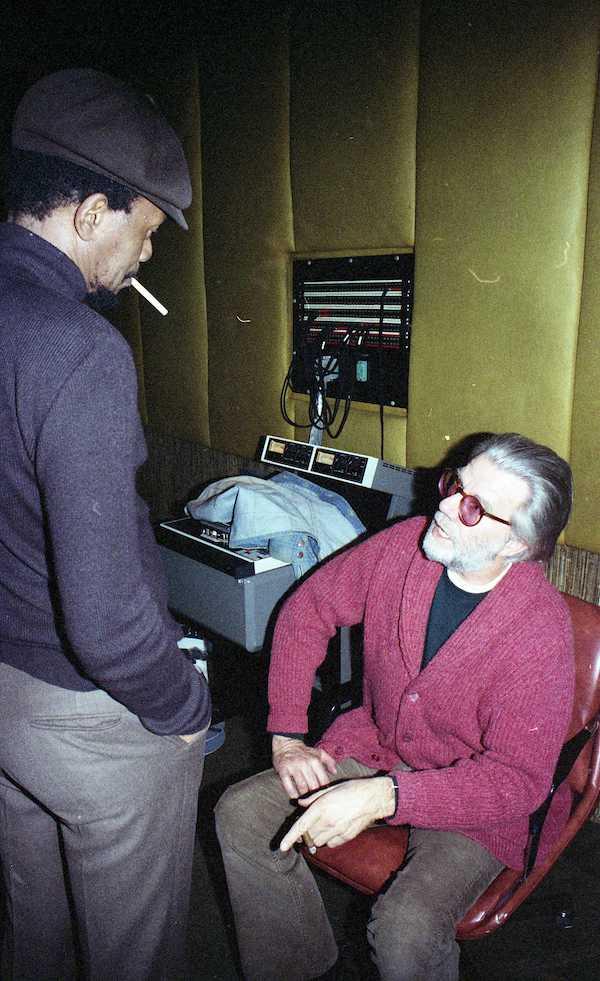

Horace is so cool that Hieronymus Bosch digs him.

Horace Tapscott, Tom Albach and the Story of Nimbus West Records

He quit the business of music, and one of the most talented jazz pianists, composers and arrangers of his generation, a charismatic figure that could have been at the forefront of jazz and commanded stages around the world, became a community activist and musician in South Central L.A. Probably, his entire recorded legacy would consist of one obscure record which he was never proud of, if not for Tom Albach, who didn’t like the system or the strings either. In fact, he hated them.

He became Tapscott’s patron with no strings attached. They worked together for seven years, and Albach documented Tapscott’s music and the music of many other musicians who, if not for him, would today be forgotten. He lost a lot of money, but never regretted it. He’s gone now, and so are Tapscott and many of the musicians, but you can listen to the music, and it’s still powerful, honest, uncompromising and unconstrained. Yeah, no strings attached.

Horace Tapscott (1934-1999) was born in Houston Texas, began piano lessons at age six, and moved with his family to South Central in Los Angeles when he was nine. Tapscott was already an aspiring professional musician and could not have moved to a better place to learn. Los Angeles, during World War II and the immediate post-war years, was a prime destination for Black migration from Texas and the Deep South, and the city’s Central Avenue clubs became hot spots for Black music. In junior high, his music teacher led a band that played for free in the parks that included Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Buddy Collette, Britt Woodman, and Red Callender. Tapscott would soon be playing with them all and learning under the tutelage of older musicians in the time-honored jazz tradition. “You’d come out of the house, and there was a well-known, world-renowned trumpet player waiting to take you to rehearsal. They were always looking out for you, and they were serious; they wanted you to learn. All the time you were riding with them, they’re talking, and they’re jamming with you.” He would never forget the education he was given and the generosity of the musicians.

By the time he was in high school, Tapscott was writing music and was playing both piano and trombone professionally, gigging with Frank Morgan, Don Cherry, Billy Higgins, Gerald Wilson, and others on the vibrant Central Avenue jazz scene. In 1952, he played on and arranged “Pachuko Hop” (the same song that was frequently played on stage by the Mothers of Invention) for saxophonist Chuck Higgins, which became an R&B hit. Tapscott never saw Higgins again and never got paid. In 1959, he went on the road as a member of the Lionel Hampton Band, playing trombone. He remained with Hampton until 1961, when disgusted with the mistreatment and the exploitation of Black musicians, he quit and decided that he would not play music for commercial purposes but would dedicate himself to what Tom Albach later called, “subterranean cultural activity” in South Central L.A. In his autobiography Tapscott explained, “I wanted to preserve and teach and show and perform the music of Black Americans and Pan-Afrikan music, to preserve it by playing it and writing it and taking it to the community. That was what it was about, being part of the community, and that’s the reason I left Hamp’s band.”

Tapscott put together a band, that he called the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, made up of musicians that did not fit into the club or studio scene. They rehearsed in his garage. It was originally composed of seven musicians that included saxophonist Jimmy Woods, who was soon to record two albums for Contemporary, and the very talented trombonist Lester Robertson, a mainstay of the Gerald Wilson Big Band. Through word of mouth, the band grew in size. The Arkestra was not only a performing organization but an educational one. In Tapscott’s words, his goal was “the education of young musicians in a non-competitive, commercial-free atmosphere of love and reverence for the music.” He and the more experienced musicians taught the newcomers how to read music and set an example of how a serious musician played and lived, the way the older musicians had done for him.

The Arkestra was also playing at fundraisers and political events for Angela Davis, the Black Panthers, communist and left-wing organizations, and raising bail for prisoners. Soon Tapscott was being followed everywhere by the police. The Arkestra rehearsal house was raided by the F.B.I. who were looking for firearms, didn’t find any but arrested the whole band, except for Tapscott who had taken a break to go home. The F.B.I. had open files on Tapscott and several band members, but the Arkestra continued its political involvement.

In May 1968, brilliant but unheralded Parker influenced alto saxophonist Sonny Criss, recorded an entire album of Tapscott compositions and arrangements, Sonny’s Dream (Birth Of The New Cool) for Prestige. The band was nine pieces and nearly identical in instrumentation to the Miles Davis/Gil Evans Birth of The Cool , but that’s the extent of the similarity. Tapscott and the Arkestra members, who had been rehearsing the music and playing it with Criss in clubs, showed up at the session only to find that producer Don Schlitten had hired a mix of jazz and studio musicians to take their places. Tapscott had already been paid and spent the money, so he was forced to allow the recording to proceed and was credited as “arranger and conductor.” In his words, “That was a rough day, a real rough day.”

While it’s truly sad to think that an opportunity was lost to hear Tapscott and the Arkestra members in 1968 playing his compositions with Criss in a studio, Sonny’s Dream is an excellent album. Tapscott’s compositions, while not as free or avant garde as his writing for the Arkestra, are far from conventional bop. Hard swinging and bluesy, with modal and free touches, they are much closer to Mingus than “cool jazz.” Criss plays superbly but the real star is Tapscott’s writing and arranging.

In April 1969, Tapscott recorded for Flying Dutchman The Giant Is Awakened , his first recording under his own name. He didn’t want to make the record. Upon the recommendation of L.A. musician John Carter who had already recorded for Flying Dutchman, label owner Bob Thiele was eager to record Tapscott, who feared, “Here was another cat that was going to exploit this Black music.” Thiele showed up at Tapscott’s house in a neighborhood “where you didn’t come by yourself if you were a white cat from New York with a pipe.” Tapscott was impressed enough to put it to a vote of the band and he was outvoted.A recording of the entire Arkestra would have been too uncommercial for even Flying Dutchman which was later to record Ornette Coleman and George Russell, so Tapscott’s piano was accompanied by two basses, drums and the alto sax of the very talented Arthur Blythe, later to record a series of albums for Columbia. All the musicians were playing together frequently in the Arkestra and had no difficulty with Tapscott’s sometimes tricky bop and Monk influenced melodies. Much of the soloing, especially Blythe’s, is quite free, but the music retains a strong sense of structure because of the memorable melodies and Tapscott’s brilliant arranging for the bass and drums, which, under the solos play a variety of rhythm figures and vamps. Tapscott’s playing, while showing the influence of Monk, Mal Waldron, Andrew Hill, and Cecil Taylor, is his own beautiful, melodic, bluesy style of free jazz piano.

After the album was completed, Tapscott felt that his reluctance and suspicion was justified and was angry with Thiele because in violation of an agreement that they had made the album was mixed in New York without his input. He felt that the piano dominant result misrepresented his music. While never outright disowning the album, Tapscott never took any pride in it.

Despite Tapscott’s reservation, The Giant Is Awakened is a very good album that in its use of compositional elements to provide structure for free playing and its incorporation of African rhythms was in 1969 at the forefront of developments in jazz. Not surprisingly, it didn’t sell well. The music was challenging, Tapscott was based in L.A., not in New York where the publicity was, and the overtly Black Power liner notes by Stanley Crouch replete with the “F” word, the “N” word, “m-----f---ahs” and references to “crackers” undoubtedly made DJs and mainstream critics decide that it was best (and safest) to ignore the record. Tapscott didn’t record again for nine years.

In the early seventies, the War on Poverty funding dried up and the Arkestra survived by scuffling. “It got to the point where they were inviting us to the elementary schools and senior citizens homes. Most of the time it was for free. When we did make money by working at the schools and the Black Students Union at some of the colleges, it wasn’t much. We’ve got twenty-five pieces and they maybe had a budget of $1000 for the whole year. We never did what you call a real tour. Years ago, we would have three or four places in the state to go, and that would be only maybe during the Black History Week at that time. We have tried several times to get federal funding, but no way they was going to give anything to what we were into.”

Tapscott personally found it hard to get other music work. His reputation for outspokenness and militancy made him persona non grata in the lucrative L.A. studios and in clubs. The fact that his music was far from the “standard dinner and drinks” jazz club fare made it even more difficult. He and his large family got by because his wife had a job, and he managed to get occasional donations, gigs, and by doing “ghost” arrangements for Las Vegas shows, Peggy Lee, Sonny and Cher, and others, which were credited to less controversial arrangers. Amidst the struggle, Tapscott never compromised. “…in the early 1970’s, I got an offer out of the blue from a white college in one of those northeastern cities to join their faculty and lead a seventy-five piece orchestra and one hundred voice choir. I have no idea how they found out about me. They just sent a letter offering me this gig, telling me how much money I’d be making and what kind of situation I’d be in. I refused it naturally, because it would have taken me so far out of the community and put me in an all-white setting.”

In the mid-70s, the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension (UGMAA), the umbrella organization for Tapscott’s community activities and the Arkestra, was given a three-story building that became not only a rehearsal space and office but also a school with music and Black History classes for children. The Arkestra continued playing in schools and began a monthly free gig at the Immanuel United Church of Christ (I.U.C.C.) which continued for nine years.

The residency at the church was a turning point for Tapscott and the Arkestra. After the first few years, when frequently the audience was considerably outnumbered by the musicians, the word began to spread, more people from the community began to show up, and surprisingly so did white people. The jazz audience was starting to pay attention. In February 1977, the “Los Angeles” column in the jazz magazine Coda mentioned the Arkestra’s I.U.C.C. residency. Soon, after, Tapscott and the Arkestra played a gig at Los Angeles’ jazz avant garde bastion---the Century City Playhouse. Tom Albach was one of the attendees.

- Log in or register to post comments

in the 1980s and 90s. That is where I first listened to Tapscott's music. Los Angeles based Interplay Records also released three Tapscott recordings. Elaine Brown commissioned Tapscott to arrange and conduct her album titled, "Seize the Time" on Vault Records. Found that at the Jazz Record Mart too. Still see it around the Chicagoland record shows every once in a while. I enjoyed reading this article.

I purchased most of the Tapscott solo lps at the Jazz Record Mart during that time, when I was a college student in Chicago (1985-1989)

Wonderful post. Thank you so much. You've filled in so many blanks and helped me make sense of the new reissues. I'm listening to my old copy of The Call right now. Gorgeous!!

Interesting that he's not explicitly calling out Outernational sounds as the other label where these are available as I'm sure these are officially licensed as well. I know the excellent Kirk Lightsey & Mallory Hall band releases through their label are using the master tapes & pressed at Pallas & sold at very reasonable prices.

However, I'm sure the new Nimbus reissues from Pure Pleasure & Kevin 'Boom 'Boom' Gray, will improve any existing pressings.

Sounds pressings for the Tapscott LPs with the tonearm jumping out of the record groove.

https://www.discogs.com/release/13406355-Horace-Tapscott-With-The-Pan-Af...

I have at least 3 that sound great. Even ERC have some pressing defects :)

I would really recommend this from the same label, it's fantastic:

https://www.discogs.com/release/16071795-Kirk-Lightsey-And-Rudolph-Johns...

I spoke with Tom Albach several times while I was a college radio dj with a jazz show (1985-1989) and became obsessed with Horace Tapscott at the time. He did, in fact, send me some promo copies of lps, though unlike other labels, I had to ask for them (they were not on cd at the time). Later, in 1992 when I moved to California, I struck up correspondence with Albach againand purchased everything released on the label. From my brief interactions with Tom, the article's depiction of him seems accurate, but my interractions were with someone who was committed to jazz and social justice, 2 things I am still commtted too. Perhaps a bit more business savy would have helped him, but I think the music industry needs more people like Tom Albach and fewer of, say, folks like Lucian Grange.

Hi, can someone clarify the sources of the new reissues? I just received a copy of Flight 17 from Pure Pleasure (haven't had a chance to listen to it yet), but there is no KG&CA in the dead wax. I'm a bit confused by the article, it seems to be saying only the Kevin Gray mastered titles are from analogue, so is this new Pure Pleasure release from a CD?

.. I agree with JW's comments regarding Pure Pleasure. All the titles I have from them are great and this is no different.

Great article by the way.