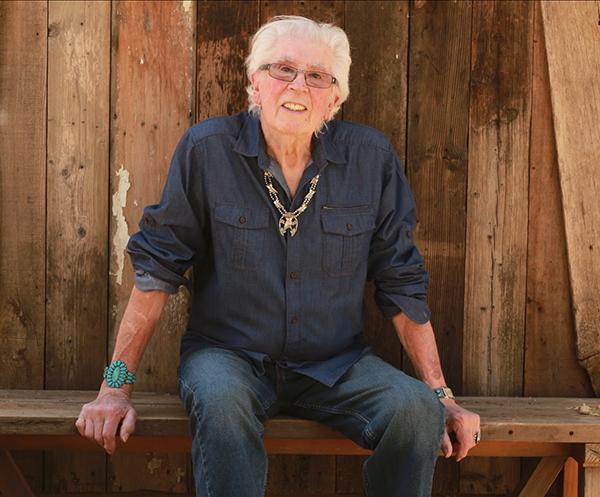

RIP John Mayall: A Deep Conversation With the Late, Great Father of the British Blues Movement of the 1960s, Whose Lifelong Mission Was to Keep the Blues Real, Especially on Vinyl

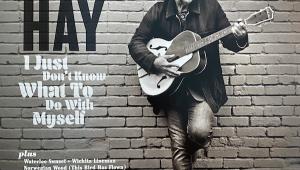

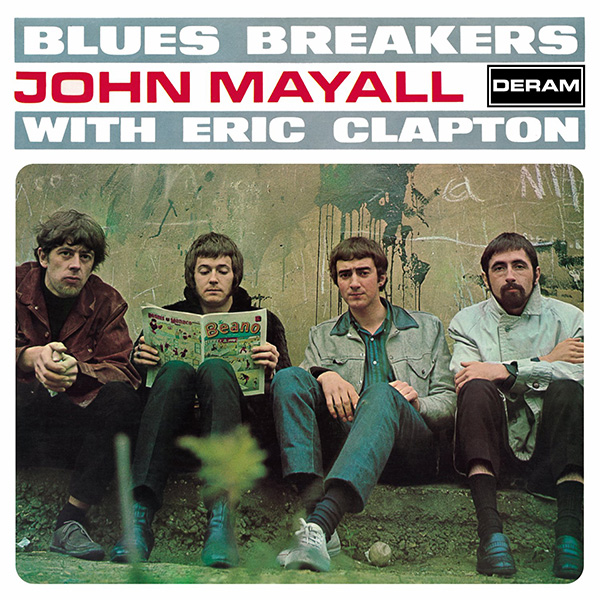

John Mayall, the undisputed father of the British blues movement, passed away at age 90 in California on July 22, 2024. Mayall emerged in the heyday of the ’60s blues-rock scene in Britain, and over the ensuing years, he shepherded the ace guitar-slinging likes of Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Coco Montoya, Buddy Whittington, and Rocky Athas. Mayall’s July 1966 album on Decca (and London in the U,S.), Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, opened the door on how artists could finally harness distortion on vinyl, not to mention that LP’s showcasing of the emerging guitar prowess of the title-namechecked man known as Slowhand.

The followup, February 1967’s A Hard Road (Decca in the UK, London in the U.S.), featured Peter Green on guitar, essentially laying the groundwork for the band Green would soon enough co-found, Fleetwood Mac. Many more seminal studio and live albums followed — some 70-plus in total, give or take — right up until Mayall’s passing. His most recent studio LP, January 2022’s The Sun Is Shining Down (Forty Below). remains a personal favorite (especially “Driving Wheel,” Side B, Track 9).

I had the honor of interviewing Mayall twice by phone to his California residence over the years, the most recent of which was a full decade ago on April 24, 2014, at high noon Eastern time. Just a few short years after that conversation, I went to see Mayall play at a fairly small club, Mexicali Live, in Teaneck, New Jersey, on September 14. 2016. Before the show, I came across Mayall sitting behind the merch table that was located just inside the front door and off to the left. He conducted all the transactions himself, sans any help — a true DIY man, through and through — and he was generous enough to sign the cover of my Blues Breakers LP (and CD) and thank me for the interview we had done in 2014.

Bookending the show with “Dancing Shoes” (from his 1999 album with the Bluesbreakers, Padlock on the Blues, which was later reissued as a 2LP set by earMUSIC in 2020) as the opener and “Room to Move” as the encore made for a magical night I won’t soon forget. Mayall’s breath control and skitch-scatting, both during and between his harmonica playing on “Move,” was as aurally mesmerizing as it was on the original live recording from his October 1969 Polydor LP, The Turning Point.

When I asked Mayall if he ever thought of slowing down anytime soon, he balked at the idea. “You have no other choice, really,” he told me, matter-of-factly. “You set your feet on your path, and that’s what you stick with. It’s the only thing that you know to do.” Not long after we spoke, a truncated version of the interview appeared over on our sister site Sound & Vision and a slightly extended version posted on my own SoundBard site, but in the wee hours after I learned of Mayall’s passing, I went back to my original interview transcription to add even more content to what you’ll be reading below. As you’ll soon see, Mayall and I discussed why he preferred to cut his tracks in as few takes as possible, what specific factor he based his sequencing choices on, and how that 1966 Blues Breakers LP truly opened up a new avenue of recording.

As we were hanging up — this is the part of any interview I do that I call “The Load Out” — Mayall paid me a nice compliment. “I think it’s been a very good interview,” he concluded. “They can vary tremendously, and you did a great job. Very easy to talk to. Alright then, see you on the East Coast.” I humbly appreciated his words both then and now, and I’m glad I saw that 2016 show. Rest in peace, dear John. ’Cause I can’t give the best / Unless I got room to move. . .

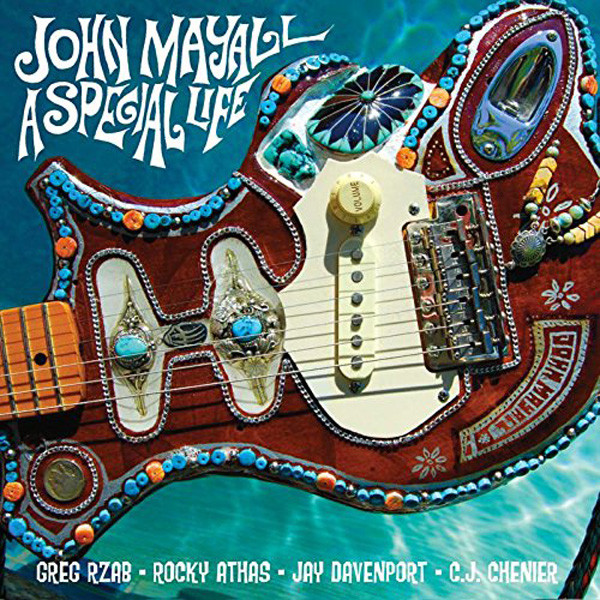

Mike Mettler: One thing that continues to astound me about you when I was listening to A Special Life [Mayall’s May 2014 2LP studio effort on Forty Below] is your voice. It’s as good and true and real as ever. How do you keep it in such great shape?

John Mayall: I don’t know. I’m just a pretty healthy individual. I haven’t had any signs of deterioration in the vocal category, so I continue to have a great time singing, and I want to give it the best in the studio if it’s a permanent record for something. Every time I go into the studio, which isn’t very often, I want to make sure it’s on top form.

Mettler: I cued up “All Your Love,” from 1966 [Side 1, Track 1 on John Mayall and the Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton], and then I played A Special Life right after it, and the vocal character is still pretty consistent.

Mayall: Yeah. Aren’t I lucky? (both laugh)

Mettler: Did you ever have any vocal training, or is it all by feel?

Mayall: It’s all by feel. I haven’t had any kind of training in any musical capacity. I’m self-taught on all of my instruments. The same with the voice. I wasn’t one to take direction from another person. It’s not something I’ve ever really been attracted to.

Mettler: It must be an instinctual thing. When I spoke with [Cream bassist/vocalist] Jack Bruce [in February 2014], I asked him a similar question. He had some classical training when he was younger, but he said it was also an understanding about how to use your muscles, and when not to use them.

Mayall: Yeah. I’m happy you got a chance to talk to Jack. I haven’t seen him for a long, long time. [Bruce played with Mayall in late 1965 and early 1966, after his time with the Graham Bond Organization and before he joined Manfred Mann, and thus had some band overlap with his future Cream mate Clapton. Jack Bruce passed away at age 71 in October 2014.]

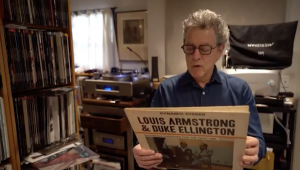

Mettler: Growing up, you listened to your dad’s 78s, which is how you started getting into music. Were those jazz recordings?

Mayall: Jazz and blues. That was the only way to listen to music back then — with your wind-up gramophone, and all these things people of this generation don’t even know what they are. (laughs)

Mettler: Gramophone — that’s an app I can get on my phone, right?

Mayall: Hah, a gram-o-phone, yes!

Mettler: When you’re recording, how do you know when the sound quality is right?

Mayall: The technology today can capture anything that you play — as long as you’re in the right studio with a good soundboard and the right engineer. Eric Corne was the right engineer for A Special Life, and he was very, very helpful. He knew all the technical stuff in order to capture what we were doing in the studio live. [A Special Life was recorded at Entourage Studios in North Hollywood, California, on November 5-10, 2013.]

Mettler: In terms of physical placement in the studio, were you all in the same room and able to maintain eye contact? How were you set up?

Mayall: It was one big room, and we were all there looking at each other when we were recording the tracks together. There were no barriers. I did a scratch vocal when we were playing the tracks, but the finished vocals were overdubbed. That live feel — I mean, you can’t get that if you’re doing everything piece by piece. You’ve got to have that interaction. The first track on the album [Side 1, Track 1, “Why Did You Go Last Night”], with Clifton [C.J. Chenier, on vocals and accordion], that was a first take. And he only played it once. We flew him in from New Orleans, and he arrived at the studio at about 11 o’clock and hadn’t even met the guys before that. By 4 o’clock in the afternoon, his part was done, and he went back home that night.

Mettler: It’s pretty amazing you got it so quick.

Mayall: Well, that’s the way I like to work. If it doesn’t gel together in that first hour, then it’s not going to work.

Mettler: You’re not a fan of laboring over recordings.

Mayall: It’s my experience that if you labor over a track and keep trying to get it right, it’s really not going to work. It really has to have that magic when you play it. It’s got to be in everybody’s mind that you’re on the same page with it. If it feels natural, then it’s real.

Mettler: People can play the feel right out of a track if you play it 30 or 40 times in the studio. The magic has to be there upfront and you need to capture it before it’s gone.

Mayall: It’s the only way I’ve ever worked, so I don’t know how other people manage to do what they do. The bigger groups that have notoriously spent weeks and months and sometimes years to come up with an album — that totally baffles me. I don’t know how that can possibly be. (chuckles)

Mettler: You can tell when you listen to certain records — they sound “produced.”

Mayall: Yeah, yeah. And the blues is a thing that has to be real.

Mettler: Is there a particular track on A Special Life you’d consider as one of your personal favorites?

Mayall: I don’t put out any album unless the songs are all personal favorites, because they all touch on different feels and different stories — as long as they’re separate from each other and have their own identities. I always look at it as a guideline for putting an album together — as if you got a case full of singles and you put them on one at a time, and they all sound different from each other.

Mettler: Inside the Special Life LP package, you list the different key each song is in.

Mayall: Fans have always appreciated that, and fellow musicians have complimented me on that because it’s very helpful to let them know what’s going on. (laughs)

Mettler: Do you choose the album sequencing based on the keys?

Mayall: Yeah, because each key has a different flavor and mood to it. It really helps to keep those things moving along, the contrast — one track ends, and the next one is kind of a surprise.

Mettler: That’s a good point. I still view an album as something that takes me on a journey as a listener. From beginning to end, you as an artist chose a specific path for me to follow, and I should respect that all the way through to get all the nuances of where you’re going. When “Floodin’ in California” (Side 2, Track 2) goes into “Big Town Playboy” (Side 2, Track 3), that seems like a natural move to me.

Mayall: Yeah, exactly. I’m pretty much old school in that regard. (laughs)

Mettler: Well, there’s a lot to be said for the old school (Mayall laughs), and it is a school worth following. Speaking of things worth following, is there one particular record that was the most impactful when you were growing up, one that made you think, “Ok, this is something I have to do or follow”?

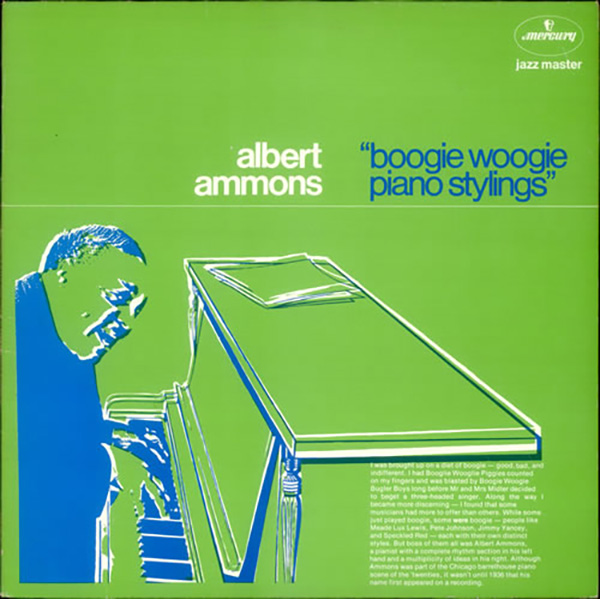

Mayall: One thing I discovered early on was boogie-woogie. Albert Ammons was probably the one who led me into the keyboards line. Albert Ammons was one of the boogie-woogie giants. That was my real starting point, my real passion.

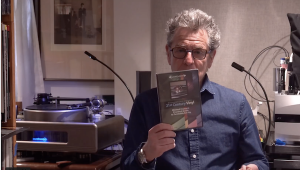

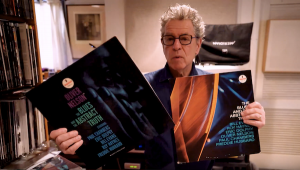

Mettler: Are there any records from the ’60s timeframe that are still among your favorites today?

Mayall: My record collection is so huge, and they’re all part of my listening experience. But Freddie King was one of the greatest influences on my singing, and certainly his guitar playing and the whole mood. There are so many people. I had the privilege to work with John Lee Hooker, Sonny Boy Williamson, T-Bone Walker — these greats who are no longer with us. Just an incredible array of people. It really was part of my upbringing.

Mettler: Would you consider any of them to be your idols?

Mayall: Absolutely, yes — particularly Sonny Boy Williamson. The way he played was different than all the other harmonica players. Just pick up any album of his. His music always comes across, and he was a great blues songwriter. Very humorous in a lot of cases too. (chuckles)

Mettler: The tables may have turned a bit, since you’re the one who’s considered an “idol” now. You’re in a position where people want to play with you.

Mayall: Well, that’s a very complimentary way of putting it. (laughs) It’s probably a thread that runs through it, when you’ve been around long enough and are still putting out music.

Mettler: I look it as you’re carrying on this tradition. Even when you started doing it and focused on the blues, there really weren’t that many people into what you were into. When you met guys like [other early ’60s British blues giants] Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies, did you get a sense of, “Oh wait, now there’s a sort of movement going on here”? Was there a groundswell at that point?

Mayall: It was very, very evident. Who knows what would have happened if we hadn’t appealed to the public at that particular point, because there was a focal point for people to gather. It fit the times of the youth culture, the fashion, the music, the movies — there was a new wave of something happening. So it all fit in with that.

Mettler: That’s right — you were the first new wave, if you want to put it that way.

Mayall: Yeah, yeah! We all felt we were onto something very exciting. We were all together on it.

Mettler: It just seemed like everything coalesced at the right time.

Mayall: It was all over the country, but the Ground Zero was London. So wherever you came from, you went down to London. The Animals came down from Newcastle. Spencer Davis and Stevie Winwood, they came from Birmingham. We all congregated in London. And it branched out from there.

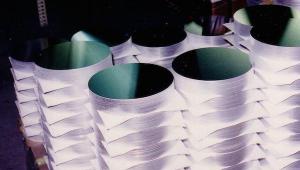

Mettler: The infamous Blues Breakers album, with Eric Clapton — that was originally recorded in mono, right? Did you have a preference between mono and stereo?

Mayall: I don’t think stereo had really come about too much. But there were only 4-track tape machines, so you had to combine them. You had to put the bass and the drums on one track, then on the two [i.e., second] track you’d put the keyboards, number three would be the guitar, and then you’d combine those tracks to make another one. It was very clever, really, but there were only four tracks to play around with, so you’d keep combining them.

Mettler: That record was cut in the early days of being “allowed” to use distortion in the studio. It was unheard of then.

Mayall: When we recorded that album, Eric was just playing at the same volume he was using during live gigs. We were playing just like we were on the road. It was kind of a new thing.

Mettler: Would any of the engineers in the studio tell you, “Hey, we can’t record it this way”?

Mayall: That’s just what the engineer in the studio at Decca said [possibly Gus Dudgeon], but the producer [Mike Vernon], said, “No, that’s the way it’s supposed to sound. Just get the tape rolling.”

Mettler: And that must have been what you wanted to hear, because that’s how you were playing it live.

Mayall: Yeah, exactly. We had a gig in the evening, and that session was in the daytime, so it was, “Hurry up and get this done.” (chuckles)

Mettler: Right; those really weren’t long sessions. You got done pretty quickly. Could you tell it was coming together right away when you were making it?

Mayall: I think so. It’s the only way I know how to work. All of the tracks for the Crusade album [released September 1967 on Decca, with Mick Taylor on guitar] were recorded in seven hours. Some of the musicians were like, “Can we do that again?” “Nope, we’ve got to move on.” (laughs)

Mettler: When it’s feel, you’ve got to do it right. You’ve said you like giving people the freedom to do their thing, but in your context. And letting people be themselves lent to better songs.

Mayall: You’ve got to capture that magic feeling of spontaneity — that’s the whole point. Once you start doing something over and over, you start to lose the quality that makes it exciting in the first place.

Mettler: Of your performances on the Blues Breakers record, “What’d I Say” (Side 1, Track 6) feels exactly as it should. Is there a particular song from that album you still feel is “the one,” the standout?

Mayall: “Have You Heard” (Side 2, Track 3) is the one that immediately comes to mind, because it’s such a great guitar solo and a great mood. And I’m still singing and playing that one today. It’s stood the test of time. I enjoyed singing on that one. And having Alan Skidmore on it — I always enjoyed his tenor sax playing. All of those elements I think make “Have You Heard” as probably the one closest to me right now.

Mettler: I have to say I like hearing “I’m Your Witchdoctor” (an October 1965 single on Immediate) being played regularly on the Underground Garage channel on SiriusXM.

Mayall: That was Eric, one of the first feedback guitar solos. It’s funny, because when we used to play that live, he didn’t always feel like doing that. It was the middle part when we played it live, and sometimes it would be empty because he didn’t feel like doing the feedback. (laughs)

Mettler: Getting feedback in the studio — do you feel like that was a revolutionary thing?

Mayall: Back then, yes, it definitely was. Eric was one of the pioneers at the time, along with Pete Townshend. It was very, very new.

Mettler: And you embraced it.

Mayall: If it feels natural, it’s a sound that’s unique.

Mettler: I also like the throughline that comes through on the [1967] album after Blues Breakers — A Hard Road, with Peter Green on lead guitar.

Mayall: That’s another one-take.

Mettler: Were you ever able to interact with Peter over the last decade or so?

Mayall: No, not really. It’s like there’s two different people. The person before whatever it was that tipped him over, his whole personality — everything is different. It’s sad.

Mettler: You were always able to keep a clear head about things yourself, all that time.

Mayall: Exactly, yeah. You’ve got to take it seriously. Life is too precious to waste. [Peter Green passed away at age 73 in July 2020.]

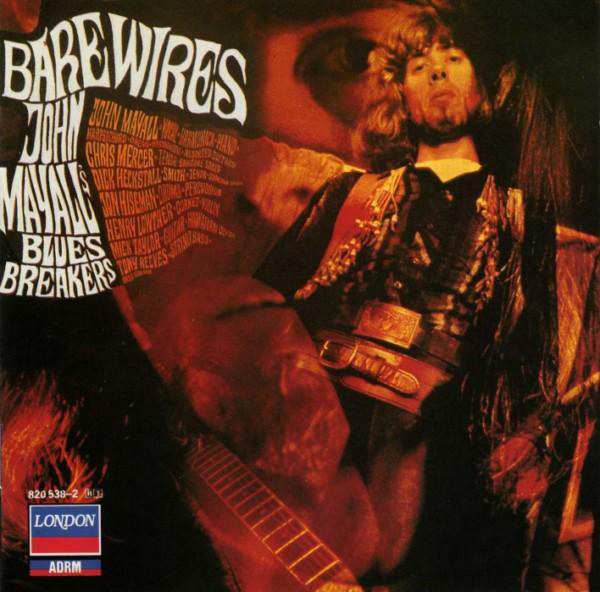

Mettler: Was the cover artwork for A Special Life a nod to some of your late ‘60s covers, which you designed? I’m thinking of the typography you used on the covers of Bare Wires [June 1968] and Blues from Laurel Canyon [November 1968].

Mayall: Yeah, that’s all my artwork there. Over the years, I’ve probably done more of the record-cover designs than the record companies have, because that was my whole training — art and graphics, typography, and all that. That’s what I thought my career was going to be. Music was just a hobby — but then the hobby turned into the main thing. (laughs) It’s all in character. I always think the artwork has to match the music that’s inside. There’s got to be a connection. So if I’ve made the music, by doing the artwork — the visual side as well as the audio side — it all comes together.

Mettler: This definitely gives you a feel of what’s inside. Is that an actual guitar?

Mayall: That’s the guitar I’ve been using on the road; it’s my guitar. When I get a guitar, I usually like to cut the body up and redesign it. So that’s my latest piece of three-dimensional art. I’m playing it a lot onstage these days. People keep staring at it, you know. So if my playing isn’t any good, at least they’ve got something to look at. (laughs)

Mettler: You’re distracting people from the chords.

Mayall: Yes, distracting, exactly.

Mettler: Playing live has been part of what you’ve done since the beginning. Did you ever think, 50-odd years down the line, that you’d still be going? Or was that never a question?

Mayall: In a way, it never is a question. When you’re a musician on the road, if you’ve got a list of gigs coming up to fulfill, that’s really the focus. And it keeps you busy to the point where you don’t really think about where it’s all going to end, if it’s going to end. You just follow the trail of gigs that have been booked for you. Then you look back and go, “Well, that a fair lot of them over the years.” (chuckles)

Mettler: Do you have a count of how many gigs you’ve played since you started doing it?

Mayall: People do ask me that. If you figure out there’s been at least 100 every year, you can do the math from there. (laughs heartily)

Mettler: Do you record most of the gigs, or all of them?

Mayall: We don’t record any of them, because that would involve a distraction, I suppose, with the added equipment; we travel light. We just show up and play the music. But it would be nice every time we did a gig where the sound in the room is nice and I think, “Oh, I wish that had been recorded.”

Also, there’s a factor that if you’re doing a live gig and you know it’s being recorded, it’s kind of inhibiting, because half your brain is concentrating on not making any mistakes or whatever. It’s kind of a restriction, you know what I mean? So that set of three Historical Live Shows, where we didn’t know we were being recorded — there’s a freedom there that you don’t usually get. [In recent years, Mayall and the Forty Below label released some of his vintage live recordings from the late 1960s in multiple volumes.]

Mettler: Finally, is there anybody you never got a chance to play with who you wanted to, or would still like to?

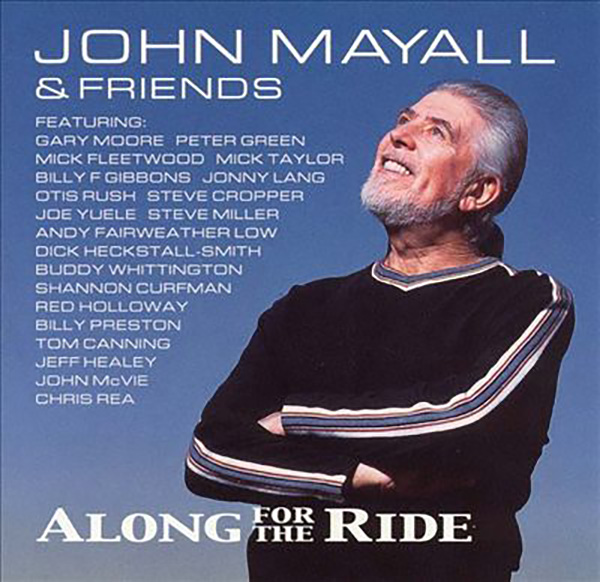

Mayall: Not really. I think the album Along for the Ride [originally released by Eagle on CD in 2001, and later as a 180g 2LP set from earMUSIC in 2018] was an example of me gathering as many people together that I had worked with before and also people I’d admired and hadn’t worked with before — people like Billy Preston, Billy Gibbons, Shannon Curfman, Jonny Lang, Jeff Healey, and Otis Rush. I got to round everybody up, and they all got a piece of the album. Quite an army of people, and they all had a go at one track. That was an exact example of what you’re talking about. So, I don’t think I need to do that again. (chuckles)