Tales Of Hoffman: Michael Fremer Speaks with Steve Hoffman: Part 1

Not that there aren't others plying his trade whose names evoke expectations of quality and good taste: Bernie Grundman, Bob Ludwig, Doug Sax, Stephen Marcussen, George Peckham, Greg Calbi, George Marino- there are others and in the future we'll try to talk to many of them- but for some reason, Hoffman's name seems to tag along with the projects he's mastered moreso than some of the others.

Why is that? Not because Hoffman is a shameless self promoter. There's been no evidence of that. None of these behind the scenes guys are. One reason Hoffman stands out is because he rose to prominence at the dawn of the CD era, when so much sonic junk was being issued.

Because Hoffman specialized in reissues, a new generation of digital sound fanatics (switching to CD from 8-Tracks and plastic turntables) took notice when they heard good sound, and more often than not, when Hoffman's name was on it, it sounded good. He was reliable.

Much of Hoffman's early reissue work for MCA stood out for its fine sound and attention to detail. Hoffman dug for masters while some others were content to use whatever was handy. No doubt you've heard some of the horror stories, or some of the horrible early CDs- like the first Impulse issue of John Coltrane's A Love Supreme , generated from the LP master tape which fades out half way through for the side change. Hoffman's name escaped such debacles. His became one to trust.

When Hoffman left MCA to join Marshall Blonstein's DCC Compact Classics a company dedicated to releasing audiophile quality gold CDs- Hoffman's star rose further.

While Mobile Fidelity was first with superior sounding gold CDs, its collectivist corporate ethic prevented any one name from taking mastering credit- an understandable tactic for a company with such strong, and positive name recognition.

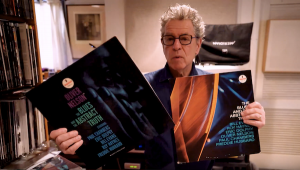

DCC by contrast, didn't have the name, so it played up Hoffman's. When the company issued its first discs: Cream's Wheels Of Fire (GZS (2)1020), Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (GZS 1021) and Fresh Cream GZS 1022), expectations ran high.

Those first releases did not disappoint, musically or sonically. To the ears of many afficienados, those three titles set a new standard for compact disc sound, as did the packaging, which included laminated facsimiles of the original album artwork.

Listeners were pleasantly surprised by the liquidity, ease and freedom from high frequency grain and texture the first DCC discs demonstrated.

Fresh Cream included extra tracks in addition to the original Atco running order. It also included master numbers, recording dates, engineering credits and information regarding track orders on original and subsequent British and American pressings, and a singles history. Wheels Of Fire also included recording information and the first issue of the long version of "Passing The Time" which was shortened for the original LP release. And DCC went to the hassle of replicating the silver foil used in the original LP packaging. Consumers paid a premium for these discs, but they got their money's worth.

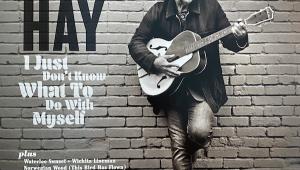

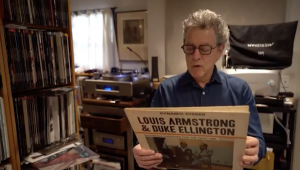

Recently DCC went back into the vinyl business with 180 gram RTI pressed records mastered by Hoffman on an all-tube cutting system. The results have been equally impressive both musically and sonically. Most of DCC's vinyl releases are worth owning both for their outstanding sonics and because the A&R choices have been smart, logical and pretty hip: Ray Charles and Betty Carter,Sonny Rollins Saxophone Colossus, Pet Sounds , and the others. While not every choice is going to please all tastes, there really isn't a serious clunker in the series so far.

When the opportunity to meet and interview Steve presented itself at last spring's Stereophile Hi-Fi show in Los Angeles, I took advantage of it. To prepare, I listened to much of Hoffman's DCC work. And I spoke with some of my Hollywood record industry contacts to get some insider perspective on Hoffman.

While no one criticized Hoffman's results- in fact all thought his reissue work was among the finest and most consistent sounding- there was some sniping: the most frequent complaint I heard was that Hoffman sometimes takes credit for the work of others, that in some cases he's given mastering credit, when in fact the actual work was done by others under his supervision.

So what? Many highly regarded painters had anonymous assistants doing some of the work on what are now considered masterpieces. And does anyone really think I.M. Pei, Philip Johnson and other famous architects do all of the design work on projects bearing their names?

By coincidence, issue 101 of The Absolute Sound, the audiophile magazine from which I'd resigned a few months earlier had arrived at the show. In it was a condescending, accusatory and innuendo laden letter from disc masterer Barry Diament criticizing Hoffman's digital transfer of The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds .

Though the technique was subtle, essentially Diament accused Hoffman of boosting the bass, playing with levels during song introductions and upping the overall level to the point of overload. The letter went on to challenge my listening abilities because I called Hoffman's disc "The Pet Sounds to own" (the vinyl LP hadn't yet been issued).

Most infuriating was that the letter represented one masterer sticking it to another based on suppositions, not facts. A five minute phone call to Hoffman could have set the record straight (as you'll soon read) before baseless and damaging accusations reached print.

Surely, Diament, wearing the same shoes as Hoffman, understood the unfairness of criticizing someone's work without having the facts, and surely he knew it would be easy to pick up the phone and speak with Hoffman- as it would be for him to pick up the phone and speak with any fellow masterer. So why wasn't the call made?

Because the real target was not Hoffman, it was I, the intention being to damage the credibility of the dear departed. The call would have nullified the letter. Of course at the time, I didn't know that Diament's suppositions were off base.

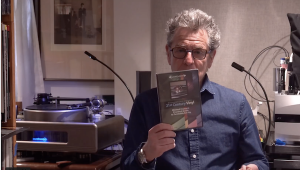

I met with Hoffman in a hotel suite set aside for the press by Stereophile. Based on my phone conversations with Hoffman, I'd built up a visual image in my head of a somewhat conservatively dressed and appearing individual with short hair, glasses and Ivy League dress. A saw a khacki kind of guy. WRONG!

A rather taller Hoffman than I'd imagined, arrived in what could best be described as a whirlwind state, with long frizzy hair, a black leather jacket, and if memory serves me well, black motorcycle boots, though that could just be my imagination filling in the blanks with the obvious and the appropriate.

I began by showing Hoffman Diament's letter. His initial reaction was extreme distress: his lip trembled and his hand shook. That turned to anger which quickly gave way to resignation: it was a hatchet job. I told him he'd have an opportunity to answer the letter in the interview and that once I had the facts, I'd fax a response to The Absolute Sound, and I invited him to do likewise. Which he did.

My rather distressed fax to The Absolute Sound written immediately after the interview was published in issue 102 (after it was agreed that the magazine wouldn't print it), as was Diament's response, which dealt more with my emotional state than the letter's substance.

Hoffman's letter, printed in issue 103, reiterates quite clearly what you'll read in the interview regarding the faithfulness of his mastering job to both the original tape and to original LP pressings, and why Capitol's version does, indeed sound different. Hoffman's point being not that Diament's preference for Capitol's version is wrong- that's his opinion- but rather that a quick phone call could have laid to rest Diament's rather damaging and incorrect suppositions as to why there are differences.

Diament's obfuscating response to Hoffman's letter once more asks sinister sounding questions which Hoffman had clearly answered in his letter. Diament totally debases himself by ending his response with a claim that all his original letter had tried to do was point out perceived differences, and that "reasons" for the differences "are of no concern to us as lovers of the music". Right. That's why he spent half of his original letter coming up with "reasons" that accuse Hoffman of revisionism in the pursuit of sales.

Hoffman is somewhat shy and softspoken. Perhaps that helped to create the physical image I had imagined. At first he was reticent and cautious, but gradually, as the interview proceeded, Hoffman opened up and delivered the goods.

M.F.: The first question I want to ask you is just a little bit of background. How did you get involved in this whole crazy business? What's your background.

S.H.: I started in radio.

M.F.: Where?

S.H.: In L.A. I was at KMET and KLAC. I was an on the air engineer and worked in the music library; jumped over to MCA Records from there.

M.F.: That was in the mid '80's.

S.H.: Early '80's.

M.F.: Doing reissuing.

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: That's what you got involved in right away.

S.H.: Reissuing, utilizing catalog was the thing that's what I wanted to do that no one else there particularly wanted to do.

M.F.: Did you work with Andy McKaie at that point in time?

S.H.: Andy hadn't been hired yet. So I went from radio to MCA, from MCA to DCC.

M.F.: At MCA when you first started working you were doing all analog to vinyl.

S.H.: Analog to vinyl.

M.F.: Did you do any of the Chess stuff?

S.H.: Chess and ABC Records, also doing a lot of jazz compilations of the 1920s and 1930s using 78 source material, and I learned a lot there about what makes things sound good, as opposed to what some were doing-just coming off of the 78s and adding echo to everything to make it sound "great" even if it's 80 years old.

M.F.: And you were taking the tapes out of the vault, when you were doing tape stuff, and you were using facilities MCA had?

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: They had their own production facilities?

S.H.: Yeah.

M.F.: And lacquer cutting facilities?

S.H.: Yes. We cut lacquers there using just a standard Neumann 76 system, and it sounded pretty good. It sounded pretty darn good there. Even the ones that I play now, it's like "Yeah."

M.F.: Well you did that two LP Buddy Holly set, right (Legend [MCA2-4184] )?

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: Now was that digitally re-mastered.

S.H.: No.

M.F.: So that's analog?

S.H.: Analog.

M.F.: The two LP set, that I've got. It's all analog?

S.H.: Yes, that's analog. The, let's see, the LP came out about a half a year after the CD. I actually went back and did it all over again rather than just use the digital compilation tape.

M.F.: Good. Now have you heard the gold CD that MCA just did of Buddy Holly material (MCAD 11213)?

S.H.: No.

M.F.: Have you heard MCA's gold CD A Decade of Steely Dan (MCAD 11214)?

S.H.: No.

M.F.: I have that here.

S.H.: What do you think?

M.F.: I only played it through once. It sounded to me as if it was a very narrow band in the mid range or upper mid range that Glen Meadows had spiked to make the guitars and everything stand out in an unnatural way. Now that may be right; it may be wrong. I don't know. Have you heard that? We can listen to it. I have it here.

S.H.: It's possible. Every mastering engineer has their own...

M.F.: It sounded to me...

S.H.: ...hearing loss.

M.F.: I enjoyed it on a certain level. You know what I mean? I don't know whether it's what the tapes actually sounded like, but I enjoyed it. I still think the records sound better.

S.H.: Steely Dan masters are notoriously smooth sounding. They're very, one might even call them "putty"sounding.

M.F.: Really? Well that's what the Moblile Fidelity Steely Dan CDs sound like -which I suspect is fairly accurate.

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: But this is bright and hard.

S.H.: Okay, it's been EQ'd down that line.

M.F.: It sounds like it's been EQ'd.

S.H.: Yeah, EQ'd, but, you know, that's what they wanted.

M.F.: Right. Perhaps the attitude is, you're paying the extra money for a gold CD, it damn well better sound different, not necessarily better, but different enough. Or perhaps I'm being cynical because I understand Becker and Fagan approved.

S.H.: Right.

M.F.: What stands out is this band in the upper mid-range and highs- where guitars are strumming, picks are hitting strings, you know. But anyway that's another issue. Okay, so now when did you end up at DCC?

S.H.: Yeah, Marshall Blonstein hired me in '87, and we immediately started working on the hot thing at the time, which was all these compilations. Various artists-we wanted to fill a void in the market place, and the main void was that you couldn't find a really great copy of "Louie Louie" by the Kingsmen. Now that might not seem like an audiophile problem, but.

M.F.: Didn't Rhino do that, didn't they have.....

S.H.: No comment. A good sounding audiophile version of "Louie Louie" is hard to find. Now there are some people who would say, "Well who cares about 'Louie Louie,' " but if you hear the real "Louie Louie" on a good system.

M.F.: It's good. Even the original Wand Records.....

S.H.: Yeah.

M.F.: Yeah.

S.H.: Yeah, well they only used one mike. It was strung up on the ceiling, so you hear this whole thing going on (snapping fingers). You know, if that's reproduced correctly, it's like a whole new thing. So we concentrated on oldies for a while, then we got the Ray Charles catalog, you know.

M.F.: Yes.

S.H.: That hadn't been utilized at all, so we called up Ray and said, "Here's who we are. We want your catalog," and he said, "Yes."

M.F.: And you did the Betty Carter and Ray Charles (currently LPZ 2005) once before.

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: That first one was on green clear vinyl, which is maddening.

S.H.: Yes. That's right.

M.F.: Maddening cause you couldn't see where the tracks were, because you were seeing the grooves on both sides.

S.H.: It was a little marketing gimmick that maybe wasn't such a hot idea.

M.F.: Now those records were digitally mastered.

S.H.: Nope.

M.F.: They weren't!?

S.H.: No. They were cut from an analog safety.

M.F.: That's still just one generation down.

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: And what is the one you're cutting now on 180 gram vinyl (the record hadn't been issued when this interview was conducted)? That's....

S.H.: Master tape.

M.F.: Master tape. So, I'm gonna hear a difference between those.

S.H.: Yes you will!

M.F.: Different chain as well?

S.H.: Yes, you will hear less of a chain. You will hear about as minimalist an LP as possible.

M.F.: This is your set up now? Where is it?

S.H.: Ray Charles and Betty Carter was cut at LRS in Burbank using a...

M.F.: What's LRS?

S.H.: Location recording service. It's one of the oldest mastering joints in Los Angeles.

M.F.: And they still have....

S.H.: They have a lot of original equipment from all different eras.

M.F.: Cool!

S.H.: We kind of brought them all together to this one Frankensteinian system. You know we interchange little parts here and there.

M.F.: So what's the lathe? Is it a Scully?

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: And what kind of cutter?

S.H.: Well, let's see, what did we use on Ray Charles and Betty Carter. It was a slightly modified Neumann. We were almost ready to use our 1960 Westrex.

M.F.: Wow.

S.H.: It would have sounded like a "shaded dog,". But I know that album so well! I could hear all the things that audiophiles love about that "shaded dog" sound. You know, high-end distortion, out of phase above 10K. I could hear all those things, but there was enough of that on the tape already.

M.F.: Right.

S.H.: So, you know, the idea was to make a clean, accurate transfer, so we went Neumann all the way.

M.F.: Now you know that Otto Hepp who built those Westrex cutters is still alive and you could get him to modify that Westrex and bring it up to date.

S.H.: I know.

M.F.: Have you thought about doing that?

S.H.: Once it's modified, the ones I've heard, they don't have that old sound anymore. Therefore, why do it?

M.F.: What do you think, have you heard the Classic Records re-issues?

S.H.: No comment.

M.F.: Really?

S.H.: Sorry, I can't get into that argument.

M.F.: Okay.

S.H.: On the record they've done a great job.

M.F.: Yeah. I think everybody who's in this can criticize one thing or another, cause they might do it differently, but that's not really the issue.

S.H.: They've done a great job.

M.F.: Okay, let's go to the gold CD's now. When you first started doing them were you using a tubed playback deck?

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: And you have a very simple chain, you have a tubed Ampex?

S.H.: It's Ampex electronics, a Scully, with some little Scully parts, the transport is Studer 80, you know, for the gentle handling.

M.F.: Right. That one's that's got the two arms, the two rollers.

S.H.: Yes. It's an old LP mastering deck.

M.F.: Yeah, Bernie Grundman uses that also.

S.H.: It's the gentlest.

M.F.: Right.

S.H.: Because those old Ampex's are brutal. I've seen those things snap old tapes. Anyway, so we're using that. If we need to do anything with equalization, we have various ones we use here and there.

M.F.: Mostly modest amounts it sounds like.

S.H.: Always modest, we never add anything; subtract something here or there if we need to, and one or two other things sometimes in the chain depending on master tape, you know, if it sounds good, if it sounds bad, if it sounds muddy, if it sounds too bright, if it sounds too dull...

M.F.: To some the master tape is God, but in fact...

S.H.: It's not God, Michael, that's for sure.

M.F.: It's a work product in many ways.

S.H.: It is, as those old wacky RCA engineers used to say, it is definitely a work part, and it is not a finished anything, although the mixing engineer would like to think so.

M.F.: But even they must realize that.

S.H.: It's not.

M.F.: Cause you're playing it back on this machine, and you've modified the heads?

S.H.: No. The heads are not modified, they're just Ampex ATR 100s. The problem is that most everything has its own sound.

M.F.: That is the point isn't it?

S.H.: Yes it is.

M.F.: That people can criticize, everything has its own sound, just like every stereo has its own sound, and if you know what you're listening for you will hear the sound of the mastering chain.

S.H.: Right.

M.F.: Okay, you take the output of this machine- you're not running it through a board....

S.H.: No board.

M.F.: Unless you have to.

S.H.: No we have a modified George Massenburg parametric equalizer that we can just run straight minus a console.

M.F.: Right, okay.

S.H.: And sometimes it's used, sometimes it's not. It all depends. Sometimes when we're doing British things, we have the same type of English equalizers that they had back in Abbey Road, say like in 1969, and we usually turn it to the opposite that they added. In other words, you know, you could hear they added 5dB at a certain level where we'd usually remove it and hear what it sounds like straight. Usually it sounds wonderful.

M.F.: Right.

S.H.: So, our equipment is ever changing, and it's how it has to be because each case is different.

M.F.: What are you using for a converter at this point in time?

S.H.: We're using a modified Wadia 4000.

M.F.: What kind of cables are you using to (Hoffman shakes his head). You don't want to say?

S.H.: Michael, I can't talk about cables because....

M.F.: You don't believe cables make a difference?

S.H.: Yes, I believe cables do, but we try all different kinds of cables. Most of the cables that we try are equalizers in a roll.

M.F.: Filters, yeah.

S.H.: I mean, you know, we've used the purest audio, and if the cable is not completely accurate, how do we know what we've got?

M.F.: Well, no you don't want an equalizer.

S.H.: No. So it, we change cables the way we change everything else in the chain, depending on the good or crappy sound.

M.F.: And you use the shortest length?

S.H.: The shortest length. The whole chain is from here to here (a few feet). That's it,

M.F.: Now, what do you think about, what's your, this coul be a bombshell. Have you played around with an SBM box.

S.H.: Oh yes.

M.F.: I'll tell you the Ryko Gold CD's are really good.

S.H.: Sure.

M.F.: Really, shocked at how good those are.

S.H.: We've actually....

M.F.: Or any 20 bit system.....

S.H.: Sure, some of them have that on there already.

M.F.: But you're not advertising it.

S.H.: No.

M.F.: Cause it doesn't matter really? Do you think it's a marketing gimmick on a certain level? In other words, you're using what sounds good.

S.H.: Right, if it sounds wonderful, we'll use it. It's hard to explain, sometimes in order for something to sound good you have to degrade it a little bit.

M.F.: I know.

S.H.: You know it's hard to imagine that in the audiophile community, but if you don't it sounds un-lifelike.

M.F.: I know what you're saying, because I think the criticism of the Classic RCA's... .

S.H.: As long as you know.

M.F.: A lot of people are saying the Classic RCA's are too literal.

S.H.: That's my call.

M.F.: Others who take that position cite a certain bloom and warmth- even if it is a resonance in the Westrex cutter. It's that quality that makes it sound like real life.

S.H.: That's right.

M.F.: You can argue that case in any direction you want, but you know, my feeling is you can't find these old RCA's, and when you can, they're going for a lot money and even then they're frequently noisy, and they have inner groove distortion, and they're compressed and equalized. What they're doing now, you may say is too literal, it's too engineering-like, and doesn't possess enough "artistry" Be that as it may..... . Okay, so now you go from the Wadia output. How are you storing this: on a 1630?

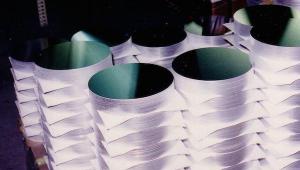

S.H.: Sure. We just store it on a standard Sony 3/4 inch U-matic video cassette. What I always do at the same time as I'm mastering the CD, I cut a lacquer at the same time.

M.F.: You do?

S.H.: Sure.

M.F.: Of everything?

S.H.: Of everything, a lacquer and a DAT and a CD copy, and I go home at night, and I play everything. I usually go back in the next day and start over again. But that's the only way I can tell, and when the CD comes back from the plant I compare it with the lacquer, and the CD master and the DAT.

M.F.: Now, how often are you surprised? And, if so, what is happening do you think that's......oh we didn't talk about the rest of your mastering chain. What are you using for amplifiers and for speakers?

S.H.: That changes all the time too.

M.F.: When you say "we" are you just using that term because it's just you?

S.H.: Yes, it's just me.... the big "We." We listen to it on what's there in the studio left over from the 1970s: old Altec monitors, or Urei monitors with old 1970s Crown amps, then we'll audition it on an audiophile system.

M.F.: Right.

S.H.: I'll make notes that way, what it sounds like here, then I'll go listen to in our audiophile setup. Let's see, what we've been using recently, are Cary 805's (single ended triode 50 watt Class "A" tube amps), and for the turntable we'll use the playback on the cutter.

M.F.: Which is what Bernie Grundman uses with an SME 3009- a transcription length one- and a Shure V-15 5MR.

S.H.: Yeah, that's a great cartridge, underrated. It's flat from like 9 Hertz! If your cartridge isn't completely flat, how can you possible tell what you have?

M.F.: Right. So now what happens to these lacquers that you're cutting for CD only releases? You just hold onto them?

S.H.: I listen to them, then I destroy them. It's only a tool to make sure that I'm not going too far afield.

M.F.: Right.

S.H.: I want everything to sound the same. You know, I don't want anyone to ever say that we were focusing in on the CD buyer over the LP buyer. It has nothing to do with the medium. It just has to do with what sounds the most natural on a compact disc. You lose a little ambience, of course, but....

M.F.: So you're willing to say at this point that a transfer of an analog tape to digital is not perfect, is not the same.

S.H.: It's not the same.

M.F.: Bernie Grundman says that when you translate languages, when you change languages, you lose something in the translation.

S.H.: Right, you lose something, but, you know, my job is to minimize that loss, and some projects I think we even gain a little bit, because some little tricks I have of adding ambience. You know, if you add a little here, and this process removes a little, what you come out with in the end is....

M.F.: a wash.

S.H.: is exactly the same.

M.F.: I see.

S.H.: And we've sat there and we've had the master tape cued up here and we're playing it, and they blindfold me and I can't hear the difference sometimes. Then I'm happy.

M.F.: Have you had any tape disasters? "Any whoops!"es?

S.H.: Not recently.

M.F.: That's good. How do you get these tapes. Do you literally go and get them yourself?

S.H.: Sometimes we fly to the company and then we courier them here, we use them and we courier them back. Sometimes they're nice enough to transport them here for us.

M.F.: Have you had any tapes delivered to you as masters that weren't masters that had to go back.

S.H.: All the time. It's not the record company's fault. The tape that's marked "Master" is usually the one that they made the LP from, and that's usually wrong.

M.F.: That's been equalized differently?

S.H.: The one that's not marked "master" the one that's marked "Do Not Use" that's usually the right one, and it's hard to get that across, you know, even after all these years. That magic word " master tape"- they think they're sending us the original.

M.F.: You can cut a lacquer today that doesn't require compression and bass summation and all that other stuff?

S.H.: Sure.

M.F.: Because the people who are playing them back have systems which can track those records.

S.H.: Absolutely. You listen to our new Ray Charles and Betty Carter.

M.F.: I can't wait!

S.H.: You know, nothing's been done. It's exactly straight.

M.F.: Who's doing the AR work, choosing the titles at this point?

S.H.: Marshall Blonstein, the Chairman of the company, and me.

M.F.: Together.

S.H.: Yeah, and it is based on consumer demand.

M.F.: You get letters?

S.H.: Lots of letters, plus what Marshall and I enjoy, what is not out there in the marketplace, what we feel we can improve.

M.F.: Are you getting into bidding wars now with the other companies?

S.H.: Yes.

M.F.: It's turning into a battlezone, and the record companies are loving every minute of it, right, cause why wouldn't they?

S.H.: Yeah. They should support this in every way. I mean it's not hurting their sales. It's a whole new market, and everybody should be happy.

M.F.: You're not claiming that the gold has anything to do with the improved sound, correct?

S.H.: It's a superior storage medium. Just hold it up to a light, hold up an aluminum CD with those hundred little pin holes in there, and just hold up a nice smooth one of these gold CDs (holds up disc).

M.F.: Who's pressing for you, can you say?

S.H.: No.

M.F.: Is it in the United States?

S.H.: Here and there.

End of Part I

- Log in or register to post comments